-

পরবাস

বাংলা ভাষা, সাহিত্য ও সংস্কৃতি

Parabaas, a Bengali webzine since 1997 ... ISSN 1563-8685 -

ছোটদের পরবাস

Satyajit Ray

Rabindranath Tagore

Buddhadeva Bose

Jibanananda Das

Shakti Chattopadhyay

সাক্ষাৎকার -

English

Written in English

Book Reviews

Memoirs

Essays

Translated into English

Stories

Poems

Essays

Memoirs

Novels

Plays

The Land Where

I Found It All-

পুত্রবধূর চোখে গৌরী আইয়ুব এবং প্রসঙ্গত

-

বিশ্বের ইতিহাসে হুগলি নদী

-

বেদখল ও অন্যান্য গল্প

-

Audiobook

Looking For An Address

Nabaneeta Dev Sen

Available on Amazon, Spotify, Google Play, Apple Books and other platforms.

-

পরবাস গল্প সংকলন-

নির্বাচন ও সম্পাদনা:

সিদ্ধার্থ মুখোপাধ্যায়)

-

Parabaas : পরবাস : বাংলা ভাষা, সাহিত্য ও সংস্কৃতি -

পরবাস | Translation | Essay

Share -

Sukumar Ray: Master of Science and Nonsense : Zinia Mitra

When I began speaking sense in my childhood, I was introduced to Abol Tabol of Sukumar Ray. I knew the poems by heart, recited them to family, friends and visitors; and I guessed by their expressions that I was speaking a lot of sense and wisdom. I grew up to find what I had learnt by heart was but unparalleled nonsense literature.

When I began speaking sense in my childhood, I was introduced to Abol Tabol of Sukumar Ray. I knew the poems by heart, recited them to family, friends and visitors; and I guessed by their expressions that I was speaking a lot of sense and wisdom. I grew up to find what I had learnt by heart was but unparalleled nonsense literature.Abol Tabol introduces us to strange people, places and animals that knock us out of our strapping reality. In one of Ray’s poems, (untitled) , a younger brother in utter disbelief narrates the commonplace incidents of our lives to his elder. “Have you heard of the place where our old doctor lives? He seems to eat rice with his hand! I’ve heard,” the younger one continues, “that he feels hungry if he goes without food, his eyes close if he’s too sleepy, when he walks his feet touch the ground, he hears with his ears and sees with his eyes, when he sleeps it seems he keeps his head headwards!” He urges his elder to visit the place and confirm such impossible occurrences. This introduces the keynote of Ray that nothing can be judged with an unconditional verdict, as there is no absolute model. The most commonplace practices, customs and conventions so strictly followed by one can be just as ridiculous to another.

BombagaR (BombagaRer Raja) is such a kingdom where anything is possible. The king hangs framed, fried and solidified mango juices— 'Chabir freme bnadhiye rakhe amsatto bhaja'. In BombagaR the queen of the state has a pillow tied to her head, while the queen’s brother is busy fixing nails on buns. Though apparently meaningless, they may mean something. Queens, in most cases, enjoy a lot of rest and the royal brother can be thought of as busy doing nothing worthwhile. The king himself howls like a fox, as many kings may, but then we come to broken bottles hanging from the throne! All of us are familiar with broken bottles and thrones, or nails and buns, but never before did we associate two such ideas together. These kinds of weird associations form the basis of Ray’s nonsense verses. In Ray’s Abol Tabol meaningless ideas combine with recognizable norms making the poems comprehensible.

BombagaR (BombagaRer Raja) is such a kingdom where anything is possible. The king hangs framed, fried and solidified mango juices— 'Chabir freme bnadhiye rakhe amsatto bhaja'. In BombagaR the queen of the state has a pillow tied to her head, while the queen’s brother is busy fixing nails on buns. Though apparently meaningless, they may mean something. Queens, in most cases, enjoy a lot of rest and the royal brother can be thought of as busy doing nothing worthwhile. The king himself howls like a fox, as many kings may, but then we come to broken bottles hanging from the throne! All of us are familiar with broken bottles and thrones, or nails and buns, but never before did we associate two such ideas together. These kinds of weird associations form the basis of Ray’s nonsense verses. In Ray’s Abol Tabol meaningless ideas combine with recognizable norms making the poems comprehensible.Masi go masi pacche hasi

Neem gachete hocche seem

Hatir matay byanger chata

Kager basay boger dim.[Dear aunt, dear aunt, how amusing

Now on a Neem tree kidney-beans grow

Elephants take toadstools as umbrellas

And the stork lays eggs in nest of crow.] Ray did his graduation from Presidency College with double honors in Chemistry and Physics and established his club, which he fondly named ‘Nonsense Club’. The very name of his club suggested the direction in which his imagination worked. The two plays that he wrote for the club—Jhalapala and Lakshmaner Shaktishel—are the first instances of Ray’s uproarious finesse. In Jhalapala the solemn teacher looking forward to opening a tutorial at the Zamindar’s house translates “I go up, you go down” as finding termites in a godown a cow sheds tears. Each word is translated in accordance with Sanskrit grammar to turn the obvious incongruous translation into a witty joke. In Lakshmaner Shaktishel the mythological characters are distorted into utterly ludicrous figures as in Aristophanes’ The Frogs. Bibhishan here is scared to confront Ravan—Ravan picks pockets; Hanuman is quite reluctant to get the magical herb ‘Bishalyakarani’ to save Lakshman’s life and has to be bribed with a banana. There are flares of witty dialogues too.

Ray did his graduation from Presidency College with double honors in Chemistry and Physics and established his club, which he fondly named ‘Nonsense Club’. The very name of his club suggested the direction in which his imagination worked. The two plays that he wrote for the club—Jhalapala and Lakshmaner Shaktishel—are the first instances of Ray’s uproarious finesse. In Jhalapala the solemn teacher looking forward to opening a tutorial at the Zamindar’s house translates “I go up, you go down” as finding termites in a godown a cow sheds tears. Each word is translated in accordance with Sanskrit grammar to turn the obvious incongruous translation into a witty joke. In Lakshmaner Shaktishel the mythological characters are distorted into utterly ludicrous figures as in Aristophanes’ The Frogs. Bibhishan here is scared to confront Ravan—Ravan picks pockets; Hanuman is quite reluctant to get the magical herb ‘Bishalyakarani’ to save Lakshman’s life and has to be bribed with a banana. There are flares of witty dialogues too.Even in these early plays the characteristic diction of Ray prevails—the language of the amused wakeful mind.

To smell the sour sky, to lick it after a shower and find that it has become sweet is a pleasant distortion of ideas that could only have occurred to a genius like Ray. His creations are unparalleled, if not unprecedented. For Ray was indeed indebted to many English writers before him.

The father of nonsense literature is known to be Edward Lear (1812 - 1888). He popularized the five-line limerick rhyming aabba.

There was an old Derry down Derry

Who loved to see the little folks merry

So he made them a book

And with laughter they shook

At the fun of that Derry down Derry.But Edward Lear preferred the term ‘Nonsense Literature’ to limerick. Oxford Dictionary registers that the term Limerick first appears in 1898, but limericks were written since ancient times. The stanzas are comic and are widely found at the beginning of 18th century and later. Limericks are included in Mother Goose Melodies for Children which appeared in 1719, while the limerick-filled History of Sixteen Wonderful Women appeared in 1821. Lewis Carroll (1832-1898), in poems like Jabberwocky and The Hunting of the Snark, later turned children’s nonsense verses into Victorian forte. The lesser-known Thomas Love Peacock wrote such ironic humor in verse too. His The War Song of Dinas Vawr begins:

The mountain sheep are sweeter

But the valley sheep are fatter

We, therefore, deemed it meeter

To carry off the latter.

The mountain sheep are sweeter

But the valley sheep are fatter

We therefore deemed it meeter

To carry off the latter.A poem might mean little or nothing. Words give us the stimulus and their arrangement draws attention. Sometimes the poets invent words themselves. Carroll combines two words into one to formulate a Portmanteau, and we come across weird sounds and words in his poems. In a unique way the meaningless words combine with recognizable words to create a comprehensible poem.

Ray, who had inherited the nonsense tradition, was also indebted to Lewis Carroll for the portmanteau words. Portmanteau terms have created new animals in Ray, like the Hasjaru (swan+ porcupine), Bakacchaap (crane+tortoise), Girgitia (chameleon+parrot), or the Singharin (lion+deer). Some of Ray’s ‘inventions’ are immortalized by being used in our native tongue frequently.

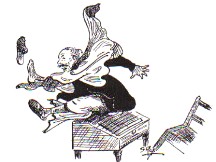

We are introduced to a series of unusual animals in Ray and all these introductions are well illustrated. Tnyashgoru is actually a bird, and Ray gives us the details of its food habits and lifestyle. His creations—KumRopotash, Hnuko Mukho Hyangla and RamgoruRer chana —have found their permanent place in Bengali lives where we compare fat men with Kumropotash, grave and serious men with RamgoruRer chana, and anglophiles as Tnyasgoru.

We are introduced to a series of unusual animals in Ray and all these introductions are well illustrated. Tnyashgoru is actually a bird, and Ray gives us the details of its food habits and lifestyle. His creations—KumRopotash, Hnuko Mukho Hyangla and RamgoruRer chana —have found their permanent place in Bengali lives where we compare fat men with Kumropotash, grave and serious men with RamgoruRer chana, and anglophiles as Tnyasgoru. These types of poems, falling under the category of light verse, commonly use the colloquial, bank on puns and treat the subjects with good-natured satire.

These types of poems, falling under the category of light verse, commonly use the colloquial, bank on puns and treat the subjects with good-natured satire.We have such gentle satire in Ray’s “Gnofchuri”, where the manager creates bedlam because his moustache has been stolen, or in “KaThbuRo”, who with his head full of strange theories researches on timber.

Lear’s and Carroll’s writings, as well as similar works in English, had positively inspired Ray. For the first rhyme in “Chite-phnota”, Ray is clearly indebted to Lear’s “Jumblies.”

They went to the sea in a sieve they did

In a sieve they went to the sea

In spite of all their friends could say

On a winter morn on a stormy day

In a sieve they went to the sea.It becomes in Ray:

Tin buRo pondit takchuRo nagare

ChoRe ek gamlay paRi dey sagore

Gamlate chneda chilo age keu dekhoni,

Gaankhani tai more theme gelo ekhoni.His “ Myao Myao Hulodada” is a translation of “Pussy Cat Pussy Cat.” His “Murkho-Machi”, as is acknowledged in Sukumar Sahityo Samagro, is again inspired by an English poem. Some of Ray’s poems proceed by associations that can only evoke laughter. In the poem “Pakapaki” he plays with the word paka (ripe) and how its application to different things gives different shades of meanings to the same word. “DnaRer Kobita” is a terrific wordplay on dnaR (oar), daRi (beard) and dnaRi (period, oarman) and similar sounding words. In “Khai Khai” he gives us a catalog of all that can be swallowed—and his list includes fists and bribes.

With Ray one has to readjust the equation that the average is equal to normal. If the equation is still valid, it is so complicated by irrationalities and absurdities that we are left questioning our norms and values. There is nothing called Absolute Reality. It is a concept that varies from person to person and from place to place. Reality may take different twists in a person at different times of his life. Lewis Carroll challenges this personal reality in Through the Looking Glass by using the genre of fantasy as does Ray in Ha-Ja-Ba-Ra-La. The very title, which is a distortion of the proper order of the Bengali alphabet, prepares us for what is to come. Carroll confronts the readers indirectly through Alice, and Ray through the young narrator. The world of the Looking Glass disobeys Alice’s established view as it disobeys the narrator’s view in Ray; so do they both disobey the reader’s view. In Through the Looking Glass, Hatter is imprisoned and punished, but the trial does not even begin ‘till the next Wednesday.’ This invalidates our established notion that the effect always follows the cause. There is also, we may say, a hint at unjust punishment so widely seen around us.

In Ha-Ja-Ba-Ra-La, Ray takes us to a world where our sturdy, conditioned mind faces a challenge. The court scene—where a sleepy bat is a judge, a crocodile is an advocate shedding crocodile tears, and witnesses are valued because they have been purchased and money is ultimately valuable—brings out the total corruption of the system in good-natured humor. When the old man asks the narrator of Ha-Ja-Ba-Ra-La his age and the narrator replies that he is eight years three months old, he is confronted with a strange question—whether his age is in the process of increasing or decreasing. How can age decrease? The Ha-Ja-Ba-Ra-La people turn their ages backward after forty. If we evaluate ourselves, aren’t most of us eager to hide our age and state our years less than what they actually are?

In Ha-Ja-Ba-Ra-La, Ray takes us to a world where our sturdy, conditioned mind faces a challenge. The court scene—where a sleepy bat is a judge, a crocodile is an advocate shedding crocodile tears, and witnesses are valued because they have been purchased and money is ultimately valuable—brings out the total corruption of the system in good-natured humor. When the old man asks the narrator of Ha-Ja-Ba-Ra-La his age and the narrator replies that he is eight years three months old, he is confronted with a strange question—whether his age is in the process of increasing or decreasing. How can age decrease? The Ha-Ja-Ba-Ra-La people turn their ages backward after forty. If we evaluate ourselves, aren’t most of us eager to hide our age and state our years less than what they actually are?A conventional model of communication has lots of loopholes. Inadequacies of model communication are seen both in Carroll and Ray. Images and words, particularly within the text, are always multivalent. As Derrida and Sassure have pointed out, one can by no means arrive at a stable signified, a stable meaning that can provide a basis for the entire system of connotation and denotation. In Alice in Wonderland in the chapter "A Caucus Race and a Long Tale" we have:

“Found it,” the mouse replied rather crossly; of course you know what ‘it’ means.

“I know what ‘it’ means well enough when I find a thing,” said the Duck: “it’s generally a frog or a worm.”

Or later in the same chapter:

“Mine is a long sad tale!” Said the mouse, turning to Alice, and sighing.

“It is a long tail, certainly,” said Alice, looking down with wonder at the Mouse’s tail “but why do you call it sad?” And she kept on puzzling about it while the Mouse was speaking …

Or when the mouse says, “I had not” Alice takes it as ‘A knot!’ and, wanting to make herself useful, asks if she could undo it.

In Ha-Ja-Ba-Ra-La when NyaRa (the bald singer) sings his self-composed songs and the narrator, unable to find any comprehensive meaning, says that it is a difficult song, the goat rejoins that only the bottles and jars are hard. He has been thinking in terms of edible items.

Or when NyaRa rhymes Sajaru (porcupine) with Majaru and the narrator protests that there is nothing called a Majaru, NyaRa dissents that if there can be a saraju, a kangaroo, a debdaru (deodar), why can’t there be a majaru too?Why not? No sound has any absolute meaning. Every latent meaning turns out to be just one more sound, searching for yet another potential meaning. We are into the Derridan impossibility of reaching meaning where everything is an endless chain of sounds.

Conventionally, a plot should have a proper beginning, middle and end. A story is an agreement consisting of word, milieu, plot, character, dialogue and style. All these blend together to form a particular genre—tragic or comic, novel of incident or character. In Ha-Ja-Ba-Ra-La, the Old Man, while telling a story, defies all of these conventions. He begins in the middle of an action; even the first sentence begins with Taarpor (and then), the characters encroach without proper introduction, and the story stops in the middle leaving us guessing for the rest . Like the senior minister in the story who has gulped down the Princess’s thread roll, the thread of the story is cut and (Ray being a conscious artist, we can say) deliberately swallowed to laugh at the conventions and critics. Defying all conventions is exciting but the society stands against the aspiring with its ‘should not’:

Bolchhi ore chhagolchhana

Urish ne re uRish ne

Janish ne tor uRte mana

Haat pa gulo chuRish ne.[Listen to me little kid

Do not aspire to fly

When you cannot have the permission

Why do you vainly try?]Ray’s target of satire is very often the polished and educated gentlemen of the society. This is evident in poems like “Tejiaan”,“Jiboner Hishaab”, “Babu”. The accompanying sketches are that of the well-dressed Bengali babu with spects. In “Bujhiye Bola, Ki Mushkil, Note Boi” Ray hits the erudite. This satire is a brawny one in Jhalapala where the Ponditmoshai (teacher) translates: “Once I met a lame man in a street near my house” to ekoda ek bagher galay haaR phutiachilo se bistor chesta korilo kintu haaR bahir hoilo naa. The grave and serious men are also objects of his ridicule. In poems like RamgaruRer chana he laughs at a lot who are scared to laugh. Such serious erudite were presumably found in Bengal in those days, and Ray himself tells us that the native place of Hnuko Mukho Hyangla is Bengal: BaRi taar bangla. Often his target is the entire mankind—for instance in Lakshmaner Saktishel, Sugrib when compared to a human being by Bibhisan protests furiously: “Don’t abuse me by calling me a human.”

Ray has parodied The Lost World of Conan Doyle in his Hesoram Hnusiarer Diary. Professor Challenger of Doyle becomes Hesoram in Ray and the Amazon forest becomes the forest of Karakoram. There the Professor confronts some outlandish animals that ravish bread and boiled eggs, animals that complain even after devouring jelly, one that only yells at the timid species and never bites. The names that the Professor gives them are amusing hybrids of Bengali and Latin: hyanglatheriam, gomratheriam, lyagbyagarnish.

Ray must have made Tagore laugh aloud, for in the preface to the first edition of Pagla Dasu Tagore praises Ray’s unparalleled Bengali light verse that excites laughter. This Tagorean preface was included in the first edition of Pagla Dasu (22 Nov 1940) and rejected in the Second Edition by Signet press (22 June 1946):

Sukumarer lekhani theke je abimishro hasyorasher utshodhara bangla shahityoke abhisikto koreche taa atuloniyo.Tnar sunipun chander bichitro o shachhal goti taar bhab samabesher abhaboniyo asanlagnota pade pade chamatkriti aane. Tnar swabhaber moddhe boigyanic sanskritir gambhirjo chilo seijonnei tini tnar boiporityo emon khelacchole dekhate perechilen. Bango sahitye bango rasikatar utkrishto drishtanto aro koyekti dekha geche kintu sukumarer hasyocchaser bishesatto tnar protibhar je swakiyotar parichay diyeche taar thik samosrenir rachona dekha jay na. Tnar ei bishuddho hasir daner sange sangei tnar akalmrityur sakorunota pathakder mone chirokaaler jonyo joRito hoye roilo.

Tagore

Kalimpong

1.6.40

[Grantho Porichoy; 5 th edition; Phonibhushan Deb] [“The spontaneous effusion of Sukumar’s humor has enriched Bengali Literature and is unparalleled. The wide gamut and the dynamic movement of his faultless rhyme-scheme, the unimaginable incongruity of his emotive associations astound us at every turn. He had a scientific sobriety in his nature and therefore has been able to evoke a play of the binaries with such promptness. Indeed, there has always been some real resonance of humor in the domain of Bengali literature but Sukumar’s hallmark of humor is unique and all surpassing. This immense gift of his refined humor along with the pity of his premature demise would forever be aflame in the reader’s mind.”]

[“The spontaneous effusion of Sukumar’s humor has enriched Bengali Literature and is unparalleled. The wide gamut and the dynamic movement of his faultless rhyme-scheme, the unimaginable incongruity of his emotive associations astound us at every turn. He had a scientific sobriety in his nature and therefore has been able to evoke a play of the binaries with such promptness. Indeed, there has always been some real resonance of humor in the domain of Bengali literature but Sukumar’s hallmark of humor is unique and all surpassing. This immense gift of his refined humor along with the pity of his premature demise would forever be aflame in the reader’s mind.”]There have been numerous instances of satire in Bengali literature, but the laughter that Ray evokes, with little trace of serious malice, is but a unique expression of a rare genius. The last flare of his genius was the last poem of Abol Tabol that he composed in his death bed where he is said to have summarized his works as toRay bnadha ghoRar dim (a bouquet of nonsense).

Adim kaaler chnadim heem

ToRay bnadha ghoRar dim

Ghoniye elo ghumer ghor

Gaaner pala sango mor.[Olden glow of misty moon

And the wreaths of nonsense croon

Softens through my spell of flute

Lulls my song and lures me mute.]To call him only a humorist is a very partial judgment of his versatile talent. Ray was an artist, an illustrator and an editor. The scientist in Sukumar Ray has never, however, received adequate recognition. After completing his graduation in Chemistry and Physics in 1906 and 1911, he received a technology scholarship and went to England to study photography and half-tone printing. At that time his father, Upendrakishore Roy Choudhury, the creator of the famous duo Gupi Gayne and Bagha Byane, (later immortalized by Satyajit Ray in Gupi Gyane Bagha Byane, and Hirak Rajar Deshe) ran a business of making printing blocks and researched printing technology. Sukumar Ray grew up in an environment of half-tone blocks, cameras and darkrooms that went into the shaping of the scientific mind of Ray, later explored in his essays for children. Gazing at the stars at night through his telescope was one of Ray’s favorite hobbies. Ray wrote an excellent article on “Pin-hole Theory” that was published in the British Journal of Photography. (July 1913 issue) Two more of his articles: “Half-tone Facts Summarized” and “Standardizing the Original” were published in Penrose Annual.

Sandesh, the monthly magazine of Upendrakishore first came into print in 1913 [Baishakh Issue]. Sukumar Ray was its editor for the first three months. Later after his father’s death (December 20, 1915), he enjoyed its sole editorship for the next eight years. Under his editorship the children’s magazine became a source of scientific information while retaining its usual short stories and poems. But there was a distinct change in the whole approach. The magazine now contained more essays on science and animal kingdom than the former issues with colorful illustrations of poetry. When the issue carried an essay on ‘Strange Crabs’, the illustration on the first page was that of a colorful crab. (Shravan 1916) When there was an essay on ‘Monstrous Spiders’ the illustration was that of a spider. (Agrahayan 1916) This no doubt enhanced the scientific flavor of this little magazine. Ray gave his readers brief sketches of famous personalities like Mango Park, David Livingston, Columbus, Iowan, Sir Philip Sidney, Florence Nightingale, John Pounds, Socrates, Alfred Nobel, Archimedes, Galileo and Louis Pasteur. The language he employed was simple, supple, entertaining and colloquial. The manner was of conversation. It did not have any erudite tinges that generally accompanied the biographies of great men, making them detestable to the young readers. Besides writing on the lives of great men, which is mandatory in shaping the minds of his young readers, he gave them lots on wild animals, marine creatures, plants and insects. This was a time when children could not turn to the Internet or click on World Books to satisfy their curiosity stimulated by so many jigsaw puzzles around them. One can well imagine the excitement of the young minds to be able to know so many strange facts from this monthly magazine. A total of 92 essays were published in Sandesh dealing with science and astronomy, on inventions like the telephone, radio, airplane, calculator, underwater telegraphic cables and skyscrapers. Such essays for children were hardly written in Bengali in those days. These essays not only enlightened the young but also served to remove a multitude of misconceptions. When Halley’s Comet was seen in the Kolkata sky , Ray set out to eliminate superstition in the minds of his young readers. In “Neeharika” he discusses at length nebula, and the birth of star in “Proloyer Bhoy” he counters the fears of doomsday:

Sandesh, the monthly magazine of Upendrakishore first came into print in 1913 [Baishakh Issue]. Sukumar Ray was its editor for the first three months. Later after his father’s death (December 20, 1915), he enjoyed its sole editorship for the next eight years. Under his editorship the children’s magazine became a source of scientific information while retaining its usual short stories and poems. But there was a distinct change in the whole approach. The magazine now contained more essays on science and animal kingdom than the former issues with colorful illustrations of poetry. When the issue carried an essay on ‘Strange Crabs’, the illustration on the first page was that of a colorful crab. (Shravan 1916) When there was an essay on ‘Monstrous Spiders’ the illustration was that of a spider. (Agrahayan 1916) This no doubt enhanced the scientific flavor of this little magazine. Ray gave his readers brief sketches of famous personalities like Mango Park, David Livingston, Columbus, Iowan, Sir Philip Sidney, Florence Nightingale, John Pounds, Socrates, Alfred Nobel, Archimedes, Galileo and Louis Pasteur. The language he employed was simple, supple, entertaining and colloquial. The manner was of conversation. It did not have any erudite tinges that generally accompanied the biographies of great men, making them detestable to the young readers. Besides writing on the lives of great men, which is mandatory in shaping the minds of his young readers, he gave them lots on wild animals, marine creatures, plants and insects. This was a time when children could not turn to the Internet or click on World Books to satisfy their curiosity stimulated by so many jigsaw puzzles around them. One can well imagine the excitement of the young minds to be able to know so many strange facts from this monthly magazine. A total of 92 essays were published in Sandesh dealing with science and astronomy, on inventions like the telephone, radio, airplane, calculator, underwater telegraphic cables and skyscrapers. Such essays for children were hardly written in Bengali in those days. These essays not only enlightened the young but also served to remove a multitude of misconceptions. When Halley’s Comet was seen in the Kolkata sky , Ray set out to eliminate superstition in the minds of his young readers. In “Neeharika” he discusses at length nebula, and the birth of star in “Proloyer Bhoy” he counters the fears of doomsday: “Had comets been a regular feature like the moon or the sun, then the hazy broom-like appearance wouldn’t have disturbed us. But they appear all of a sudden without any intimation; that is why men value them so much. All over the world men treat comets as an omen. When a comet appears in the sky all kinds of calamities are attributed to it.”

“Had comets been a regular feature like the moon or the sun, then the hazy broom-like appearance wouldn’t have disturbed us. But they appear all of a sudden without any intimation; that is why men value them so much. All over the world men treat comets as an omen. When a comet appears in the sky all kinds of calamities are attributed to it.”He goes on to discuss meteors, the rain of meteors and lastly the total solar eclipse and adds: “It is but expected that those that are illiterates or barbaric not finding any explanation of this sudden hiding of the sun, will obviously be upset, and move nervously like madmen.”

In Abol Tabol and Ha-Ja-Ba-Ra-La, Ray’s imagination takes us to an incongruous world. The same imagination reined with logic takes almost a prophetic turn in his essays and takes us to a congruous future. After the successful launch of rocket in 1920, Ray predicts in his essay “Chnadmaari” that very soon we shall have rockets carrying two or three men to space and have astronomers set to travel to the moon. In “BhnuiphoR” Ray deals with the possibilities of an underground transport system. To the scientific temperament of Ray, Darwin’s Theory of Evolution was an obvious logic to be accepted. This is reflected in many of his essays. In “GhoRar Janmo” he begins at the beginning:

“Long time back our earth was desolate. It was then like a hot cauldron. When it rained the water boiled furiously. Gradually it cooled down and plants and animals began appearing on it.”

He gives his readers a brief on prehistoric and present day animals and adds:

“This very civilized, very intelligent man, if we ever explore his history, then we’d reach a position where we won’t recognize man as a man.”

He busied himself with the ancestry of bats (pterodactyl) in “Sekaler BaduR” and with that of the tiger in “Sekaler Bagh”. In “Manusher Katha” he says:

“It isn’t quite strange that man wasn’t always a man and that he evolved in the course of the time. Which of the prehistoric animals gradually took the shape of a man cannot be known for sure. The little we know is that man is closely related to the monkey, especially the ape.”

Sukumar Ray passed away in September 1924. Had he lived longer, he would have been glad at the development of the scientific temperament of a generation that had once been the readers of his Sandesh.

Notes & References:

1. Sukumar Sahityo Samagro 3rd ed. Ed. by Partho Basu and Satyajit Ray

2. Preface to the same.

3. Sukumar Sahityo Samagro 5th ed. Ed. Partho Basu and Satyajit Ray

4. Preface to the same.

5. A Game of Words: the Ambiguities of Language in Great Expectations and Through the Looking-Glass --Katie Krauskopf '97 (English 73, 1995).

6. The Chatto Book of Nonsense Poetry, Ed Hugh Haughton Chatto & Windus London 1988.

7. In Alice in Wonderland Alice’s helpless speculations put to question the traditional concept of unitary self and coherent human consciousness: “‘I must be Mabel after all’ she continues her speculation ‘…who am I then? Tell me first, and then, if I like being that person, I’ll come up: if not, I’ll stay down here till I’m somebody else’.” In Ray in the poem “Kimbhut” we are confronted with a kind that wants to inherit the best of every species: the cuckoo’s voice, the lion’s temperament, the elephant’s trunk, kangaroo’s leap, and ultimately ends up into a nameless selfless entity.© 2005 by Zinia Mitra

Published May, 2005

Tags: Sukuma Ray, Lewis Carol, Parabaas Translation - এই লেখাটি পুরোনো ফরম্যাটে দেখুন

- মন্তব্য জমা দিন / Make a comment

- মন্তব্য পড়ুন / Read comments

- কীভাবে লেখা পাঠাবেন তা জানতে এখানে ক্লিক করুন | "পরবাস"-এ প্রকাশিত রচনার দায়িত্ব সংশ্লিষ্ট রচনাকারের/রচনাকারদের। "পরবাস"-এ বেরোনো কোনো লেখার মধ্যে দিয়ে যে মত প্রকাশ করা হয়েছে তা লেখকের/লেখকদের নিজস্ব। তজ্জনিত কোন ক্ষয়ক্ষতির জন্য "পরবাস"-এর প্রকাশক ও সম্পাদকরা দায়ী নন। | Email: parabaas@parabaas.com | Sign up for Parabaas updates | © 1997-2025 Parabaas Inc. All rights reserved. | About Us