-

পরবাস

বাংলা ভাষা, সাহিত্য ও সংস্কৃতি

Parabaas, a Bengali webzine since 1997 ... ISSN 1563-8685 -

ছোটদের পরবাস

Satyajit Ray

Rabindranath Tagore

Buddhadeva Bose

Jibanananda Das

Shakti Chattopadhyay

সাক্ষাৎকার -

English

Written in English

Book Reviews

Memoirs

Essays

Translated into English

Stories

Poems

Essays

Memoirs

Novels

Plays

The Land Where

I Found It All-

পুত্রবধূর কলমে গৌরী আইয়ুব এবং প্রসঙ্গত

-

বিশ্বের ইতিহাসে হুগলি নদী

-

বেদখল ও অন্যান্য গল্প

-

Audiobook

Looking For An Address

Nabaneeta Dev Sen

Available on Amazon, Spotify, Google Play, Apple Books and other platforms.

-

পরবাস গল্প সংকলন-

নির্বাচন ও সম্পাদনা:

সিদ্ধার্থ মুখোপাধ্যায়)

-

Parabaas : পরবাস : বাংলা ভাষা, সাহিত্য ও সংস্কৃতি -

পরবাস | English | Novel

Share -

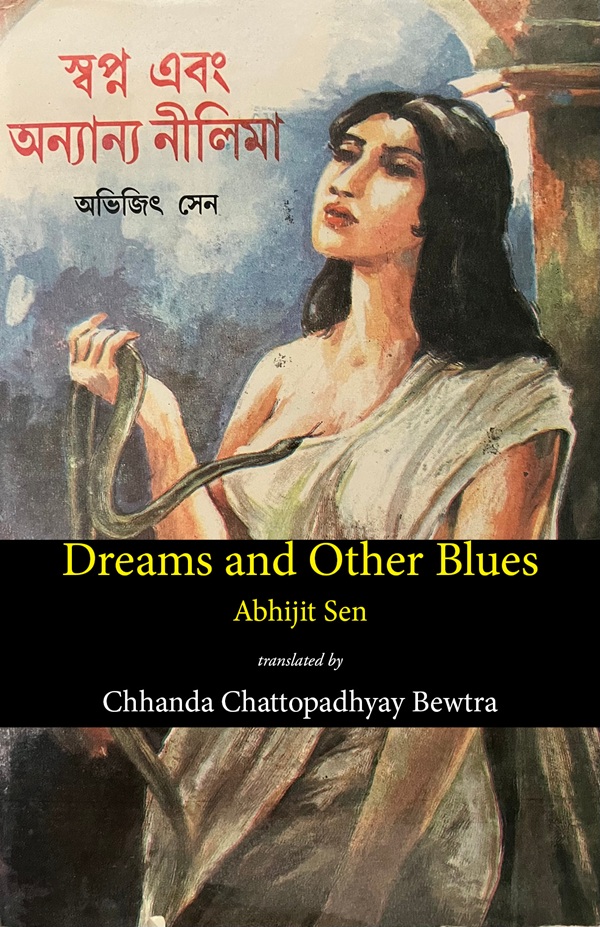

Dreams and Other Blues (4) : Abhijit Sen

translated from Bengali to English by Chhanda Chattopadhyay Bewtra

Abhijit Sen's novel স্বপ্ন এবং অন্যান্য নীলিমা (Dreams and Other Blues) first appeared about 28 years ago in a special issue of Pratikshan. After considerable revision, it was published as a book in 2000 by Dey's Publishing, Calcutta.

Abhijit Sen's novel স্বপ্ন এবং অন্যান্য নীলিমা (Dreams and Other Blues) first appeared about 28 years ago in a special issue of Pratikshan. After considerable revision, it was published as a book in 2000 by Dey's Publishing, Calcutta.

8.Hena and her comrades battled in the jungles and marshes. No, she didn’t follow a lover into the war. She had made her own decision.

She never thought of anybody greater, higher or more courageous than herself. She never thought herself weaker or lower than anybody else, either.

The Indian army led the Muktibahini soldiers in the border areas, as it did on the battlefields near Majher Bondor. Carefully sneaking into enemy territory, they would ambush the enemy and then quietly return to India. They had a good supply of arms, food, and all the modern communication facilities. Most importantly, they had the security of being able to run back home if attacked or chased. They knew what to do and what not to do, and, lastly, they knew why they were fighting.

But Hena’s group had none of these things. Their aim was to free the inaccessible, remote rural areas first, and from there gather enough strength to attack the towns and cities, and finally the capital, Dhaka. Throughout 1970, she was an active member of her party based in Dhaka. Early next year, in January of 1971, she went underground, ultimately settling in the impenetrable Jugi marsh in Faridpur. Major rivers were connected with these marshlands that were spread for miles across Faridpur and Barishal.

It was hard to keep track of all the numerous rivers and canals. Every village and town seemed to have its own namesake river, and those names changed at every turn, within ten miles or less. The monsoon rains would drown the entire area; the water would be shallow in some places and deep in others, where it stayed all year long. The mat-making reeds made an impassable jungle in the marsh of Kotalipara. And that was where they made their base camp.

In fact, Hena’s group had launched the struggle long ago, even before the March announcement. Following the Naxalbari uprisings, the Maoists in East Pakistan organized themselves and split off. In a similar guerrilla warfare, they attacked as a first step the landowners in small towns and villages, before bringing on the fight in the urban areas. Unlike their West Bengal compatriots, identifying the class-enemies was easier here across the border, as the law abolishing the landowners never really took hold in Pakistan. The new landowners had occupied the estates of the Hindu zaminders who left, and instead of distributing the land to the landless farmers, they became even stronger. As a result, the Maoists in East Pakistan right away managed to slay hundreds of landowners. But, to their disappointment, this movement didn’t culminate in an organized army like the Muktibahini.

Suddenly, at this time, the Awami League called for Independence and received roaring public support. The communists of East Pakistan erred in identifying the ‘main cause to fight for’. Instead, their guerrilla units got entangled in fighting the Pakistani Army as well as other groups that sought independence from Pakistan! Their leaders never considered severing the eastern region from Pakistan. So, even before independence, they were getting rapidly decimated by fighting on two fronts.

The base camp of Hena’s group in the marsh was quite secure. The attackers could swiftly invade the villages by motorboats and, after a quick barrage of machine-gun fire, return to their shelter. Sometimes they even dared to step on the ground, guided by the supporters of the Shantibahini and Rajakars who had gathered information beforehand. They went to those villages where people, seeking safety, had already fled to the camps of the communists or other armed groups.

Hena’s temporary base camp was in a guava grove inside the marsh. The base camp consisted of four platoons, each with twenty-five to thirty guerrillas. In this life-or-death guerrilla warfare, heroism and brutality often blurred together. Sometimes, brutality was considered even more desirable than heroic acts.

They didn’t have enough provisions for warfare. Neither arms nor food supply. In those terrible days, the only way to secure supplies was to loot an enemy camp or contact the Indian army for help. The latter method was more difficult: contacting the army across the border from the far southern provinces, earning their trust, and buying or otherwise procuring ammunition were next to impossible. Still, they did collect some. So, they had to venture out of their camp even though Albadar, Rajakar and Shantibahini had occupied the main towns and cities, even the prosperous villages. And they were the eyes and ears of the Pakistani army.

Hena traveled overnight from Faridpur to Dhaka, hiding in the hull of a large launchboat, swaddled in a burkha as the wife of some Chanu Mian. From there, she boarded a boat covered with a thatched roof and reached their secret destination, Jugi’s marsh, before dawn.

They all had promised not to die helpless in bed. She, Yakub, Arup, and Vilayat. They had pledged to die on the battlefield with rifles in their hands or celebrate victory in the capital. But returning to Jugi’s marsh, the old thoughts about death preoccupied Hena’s mind. Those thoughts visit one at puberty, suddenly overwhelming, surprising and saddening. She never had time to think if she could be confident in her decisions. A single copy of Thoughts of Mao inspired Hena as much as it could to the ideals of Communism, sacrifice, and being a committed revolutionary.

So, not lying dead next to her rifle, she instead remembered the war preparations in Dhaka, seven or eight years ago, during the India-Pakistan war. The warplanes were tearing up the sky, and the horrible pictures of war in the newspapers and magazines had imprinted on her innocent teenage mind. How clear was the blue sky over Buriganga, how colorful the waterway from Dhaka to Khulna or Barishal, the sea at Chattagram, the coconut or betel nut jungles in the west! She couldn’t tell anybody the state of her mind, nor could she explain her depression. She had written to her uncle, wailing: ‘Is India going to kill us all? Will we all perish in this war? Will they bomb Dhaka? Why? What have we done to them?’

That was when Abdul Kuddus first became aware of his niece. Trained in Marxist politics, Kuddus harbored certain opinions about religion. Islam had a kind of military discipline. Sikhism was similar in this respect. Religions based mainly on one or two texts, in Kuddus’s opinion, tended to stress military rather than moral discipline. Thus, the followers of these faiths developed pride in their physical valor and strength. The younger and less educated among them, with more passion, tended to become more insolent and pretentious. Kuddus was familiar with such people. Till then, he hadn’t realized that religious faith would again raise its head to support a specific political belief. Till the mid-sixties, he and many others like him felt that society and civilization were progressing appropriately on the path of class struggle. That most people in Pakistan didn’t harbor an iota of doubt about the invincibility of their religion made Kuddus feel unsatisfied and ill at ease. Even in Europe, people didn’t realize that certain revolutionary doctrine could fuel religious self-righteousness.

Thus, Hena’s letter offered him a sort of secret satisfaction. A hidden pride that only grows out of the feeling that one’s judgment must have been correct. It had to be. The new generation in Pakistan was at last coming out of religious passion and superstitious fog. The educated young generation seemed to be moving away from traditionalism. He felt very excited.

Kuddus was in Rongpur for his party's meeting. His reply to Hena’s letter was passionate as well as sincere according to his understanding at that time:

‘A revolution’s fire burns down to the ground all the counter-revolutionary movements. We shall all fight that last battle. And we’ll win. Yes, it’ll be a terrible battle. But are you scared? This war between India and Pakistan is only a subterfuge by the leaders of both countries to avoid their own domestic problems. They will resolve it in time, but not before a few poor people directly or indirectly lose their lives. I don’t think this war will last long. Why do you think of yourself as being alone? People from both countries face the same peril. You and I, too, are included among those people just as any other man on the street. If you can think of yourself as unified with other people, you will find the fear is gone.

Seeing the Himalayas from Rongpur was a once-in-a-lifetime experience. Just a brief glance at Kanchanjangha brought tears to my eyes. I felt selfish thinking of all of you. I do hope this war will end soon. Next year, we must come here and see Kanchanjangha together. At least try to.’

During the four months in Jugi’s marsh, Hena remembered her uncle’s letter whenever death terrified her and made her feel helpless, and that happened quite often. She read it so many times that the letter was lodged in her memory. It was the first time an adult had taken her seriously and written something of significance. All of a sudden, she felt grown up. But she didn’t understand why he included the bit about Kanchanjangha. She wasn’t old enough to question it, though she could feel something which she couldn’t quite grasp.

Seven months later, in December, when she was drifting in and out of consciousness, lying on a wet bed in a cold, damp room in Majher Bondor as Pakistani guns aimed at the town, she could see the golden spires of Kanchanjangha. As if someone with a large lens was reflecting the sun on the snowy peak, again and again. And as the peak glowed, she couldn’t tolerate the penetrating light and closed her eyes. At last, she saw the mountain flash brilliantly for the last time, and hundreds of cymbals and drums rang out. Kanchanjangha turned its glowing face; cymbals rang. It turned the other golden face; drums and cymbals rang out again. She was afloat in a golden flame that lit up the whole sky.

Shafi visited her about a month and nine days after her arrival in Jugi’s marsh. . Shafi wasn’t her lover but a very close friend. It was difficult to tell a lover from a very close friend like Shafi. Shafi was stuck in Jagannath Hall when the murders took place on the 25th of March. He had managed to hide on the roof, inside the water tank, behind a shelf of books, sometimes even feeling the breath of his murderers. He saw Pakistani soldiers in action—committing indiscriminate genocide. Folks who would be killed the next night had to bury the already dead bodies and the headless corpses. The soldiers—terrorized and violent—arbitrarily shot their rifles and machine guns at whoever came in front of them, raped without even ejaculating—such was their terror.

Even Shafi couldn’t tell how he survived—was it because of the steps he took, or was it just plain luck? He once fell from a height but wasn’t seriously injured. Bullets missed him, even soldiers missed him, when he crept in front of them. Like the Phantom or Spider-Man, he became invincible just so that he could stay alive. He felt like Joan of Arc -- ready to be the leader of the revolution.

Shafi brought them news of many more killings, destruction, rapes, blockades, and episodes of resistance. Hearing these made them even more enraged. They screamed, cursed, and fired at the surrounding bushes. Only killing someone could have sated their vengeance.

After ten days in the marsh, they were summoned to Annubhai. Anwar Choudhury was the commander-in-chief of the local revolutionary communist force. He was already famous in the entire country. He sat with his aides on a four-foot-high bamboo machan. He was tall and spare like a long-distance runner. His strong, bony build hinted at extraordinary mental and physical strength. The muscles of his jaw moved as he spoke. His sharp, mobile eyes under short brows were cruel but occasionally danced with humor, too. His hands were hard as fire irons. He quoted Mao in greetings and said, “Red salute, comrades. Revolution is not a feast or needlework party; hope you are already aware of it.”

One of Anwar’s aides was a man named Gagan Mallik. His habit was to encase each of Anwar’s sentences in a theoretical wrapper. Phrases like “Lenin always said...’ or ‘As Mao had noted...’ spewed forth from his mouth as long as Anwar spoke.

Hena didn’t like this pair. From the very beginning, she felt uncomfortable in front of them, like a woman feels with her sixth sense. But Shafi, Yakub, and others had become disciples of these harsh communists. Shafi had witnessed the ultimate in violence. He was eager and restless to do something.

9.

Manish took care of Saroj’s employment and left for Calcutta. The job was already arranged through Tridib. It wasn’t a typical job. It was temporary work for emergency situations only. Once the situation was resolved, you were dismissed. No use anymore. But during this uncertain time, when he had no contact with anyone, and none was possible, Saroj had no recourse but to accept the offer. At least he could live safely and keep an eye on the events.

By now, a ‘Refugee Camp Workers Committee’ had sprouted up. An enthusiastic leftist worker listed the workers' demands and planted the seed of a future movement, so that, in time, they could secure permanent employment. But the workers themselves weren’t sitting on their hands either. They had plenty of opportunities to earn money through illegal means, and no worker failed to take advantage of them. One colleague jokingly told Saroj something true. “There is a storm,” he said, “Tons of mangoes have fallen on the ground. If you don’t pick them up, only goats and cows will eat them.”

After hearing that, Saroj couldn’t muster any contempt towards his colleague. The man soon upgraded his house near the town on the other side of the river. Saroj was still not surprised. What surprised him was that his colleague erected a large temple before working on his own house. The temple was at least thirty feet tall, with a brass pitcher on top. The idol inside was, of course, goddess Kali. He even invited Saroj to the dedication ceremony.

Manish never came back after his marriage. From Calcutta, he worked out some tricks to move his job somewhere else. Saroj never guessed that he wouldn’t return. No one from southern West Bengal wanted to relocate to the north. The government officers considered it an exile. They tried every trick in the book to avoid such a fate. And if they had to move north, they would try their best to go back south as soon as they could.

Saroj was surprised to see such opportunism in Manish and that he had kept it secret from Saroj. T After failing twice the qualifying exam in Surgery, Manish couldn’t move to Calcutta to pursue higher degrees. So, he took the secret route. Yet since childhood, he had tried to remain honest and uncorrupted. This duplicity of character surprised Saroj but he couldn’t blame Manish either. Perhaps his gratitude to his friend stopped him. But his own weakness also made him uneasy. In fact, in the past five years, after getting away from all the mayhem, he had learned to analyze each event and character in detail and from different perspectives. This was quite a surprise to him. Even until recently, they were proud of the scientific truth of their politics and philosophy. Now it seemed there was some error somewhere. Why would Manish, even while supporting communism and related work, get interested in corrupt ways? Why would Bikash, being such a progressive in his thoughts, wear rings and amulets to propitiate various gods? Saroj no longer tried to analyze such things. Now he realized that each person could remain true to himself while coexisting with such contradictory ideologies, whatever that might signify.

After settling well, Manish finally wrote to Saroj after two months:

‘Hope this will not inconvenience you. The hospital people will tell you to move in a couple of days (if they haven’t already) because they have already received the papers of my transfer.--’

As a result, Saroj had to look for a new place. Manish’s neighbors Atashi and Krishnapriya had already moved away to another house. Atashi had retired, so they had to leave their hospital quarters. Saroj didn’t know anybody else in the town, so he ended up on Atashi’s doorstep. Krishnapriya welcomed him with his sad, childlike face, tearful eyes, and a helpless body. He tried to say in English, “You are most welcome, young man.” Even though his ‘most’ became ‘mosth’ and ‘welcome’ after stumbling twice became ‘oilcome’, Saroj felt overwhelmed with the assurance of a shelter. They both needed each other. Self-interest often proved more practical than human relationships when both parties acted wisely. In other words, a selfish relationship is also a humane relationship.

However, Saroj didn’t agree to become a member of their family. It was fine to be of help, support, and shelter each other but not belong to the family. His three brothers had separated while he was absent from the family. It was a painful memory. A single family can break apart, but the parts seldom come together.

Krishnapriya gave a toothless smile and said, “I get it. You don’t want to get entangled. Fine, just stay with us.”

Since then, he had stayed with them in one rented room. Once, he got a viral fever for eight to ten days. He felt so weak as if he could never again be able to stand up on his own. For the first few days, he didn’t want to accept help from Atashi, but later he was forced to. Every night, his fever would abate, and the sweat-soaked bedclothes would stink the whole room. He wanted to cry in helplessness. Despite himself, he would call Atashi. The fever had taught him the real meaning of loneliness.

After moving in with them, Saroj went to the schoolhouse the next morning in search of Sati. He had found a house for them. He needed to find out if she would like it.

Sati wasn’t in the camp. Abdul Kuddus said that she and Hena had gone to see another house. Many agents were working around the camp. Saroj thought of warning Sati’s mother and uncle about them but stopped himself at the thought of showing unwarranted interest.

Abdul Kuddus said, “Please have a seat. They should be home shortly.” But looking around, the man was disappointed. There was hardly any place to sit. There were people all around. Hundreds of them crowded in the partitioned barracks of the school compound. Even outside. Human trash, including feces and urine, was everywhere. Naked or half-naked children, teens, and even adults had lost their human modesty after malnutrition, disease, and desperation. Their bodies were emaciated, but their feet and legs were swollen from walking long distances. Saroj felt physically ill just looking at them.

He said, “No. It’s ok. Yesterday Sati had asked me to look for a house, that’s why--”

Abdul Kuddus came out with him to the street and said, “They had gone a long time ago. Should be here any minute.”

Saroj said, “It’s alright. I’ll look around the camp.”

In the schoolhouse, one family of four in a room on the west side had contracted enteric fever. Saroj was concerned that four of them were ill, but was reassured that it was only one family. If only one family, it was perhaps not cholera, just a food poisoning type. But he still felt nervous and made arrangements to transfer them to the local hospital. There was no vacancy in the hospital either. Saroj had already witnessed people lying outside with saline bottles hanging from log poles. He asked the workers to spray bleaching powders. As he came out, a blob of feces fell from the overhanging ledge just a few feet away from him. Looking up, he saw the naked bottoms of eight or ten boys about eight to twelve years of age collectively defecating on the narrow ledge of the roof. Defecation itself wasn’t a rare sight, but such collective work with the danger of falling was unprecedented. Saroj quickly stepped away before another hit and saw drips of dried-up feces along the walls like molten candle wax. He wasn’t as busy as on the days of distributing ration slips. So, he decided to visit the rows of barracks in the school's main compound.

From a shack in the barrack two young men stepped out. Although their outfits weren’t like the police's, both had SLRs on their necks. One sported a beret like Che Guevara's, with a matching mustache. He was over six feet tall and powerfully built. His companion was short and carried an ill-suited rifle. One more youth followed them. Saroj knew his name, Mannan. He lodged in this camp. The two newcomers were clearly Muktibahini. They talked as they walked to the street, where a dusty jeep waited, its driver at the wheel. The first two men got in front, Mannan entered from behind, and sat in the back. Saroj wondered if Mannan was joining the Muktibahini. He stood there for some time looking at the disappearing jeep.

Muktibahini’s politics were not very clear. The Indian army was training them before sending them in. They would harass the Pak army and run back. The overall politics were totally unclear to them. They vaguely understood that they were to make Bangladesh independent but had no idea who would be the leader or what type of country it would be. Such things didn’t interest them. Mujibur Rahman was the icon of this movement. History placed the burden on this unprepared man to lead a nation. Till the last moment, he had no idea what was going to happen. Indian army and Indian media provided Muktibahini with all the political, military, and ideological training.

A little distance beyond the road was a paddy field. The day was exceptionally bright. On a clear day like this in the month of Bhadra the blue of the sky was indescribable. The young paddy shoots had just started to turn dark green. It had been a good monsoon season; the paddy shoots were half submerged in water. The blue sky overhead was so bright and vast that staring at it made the memory of the four-hour-long gunfight of last night seem unreal.

Saroj walked on along the road and saw Sati and her sister returning. In normal circumstances both the sisters looked pretty but Hena was more attractive. He had seen Hena only once on the first day when both looked quite devastated. He kind of guessed then that they might be beautiful.

Today Saroj took a good look at Hena. She was beautiful no doubt. About twenty or twenty-two years old, she was taller than Sati by a couple of inches. For a slim girl, she had noticeably large breasts. Perhaps it looked large because of her height.

“Are you coming from our place?” Sati asked. “We had just gone to see a house. But it’s no good, can’t stay there. This is my sister Hena.”

Sati looked proud showing off her pretty young sister. There were dark circles under Hena’s eyes. Saroj looked closely at the dark smears on her eyelids and brows too. She looked like an exhausted dancer after spending long hours on stage.

Saroj, by habit, raised his hands in greeting but Hena already made her namaskar saying, “Namaskar, Apa still can’t forget her adab to do namaskar, yet she’s the one who lived in Calcutta. Wow! You are so handsome! You knew Apa from Calcutta, right?”

Saroj was startled. Before he could recover, Hena asked, “Did you guys have an affair, Apa?”

Behind Saroj’s back Sati pinched Hena hard, “What are you doing?” Sati scolded Hena in a subdued voice and then looked at Saroj saying, “Don’t mind her, Sarojbabu. She’s still a child.”

Hena caught her last words and said, “There’s nothing childish or old about a woman. The only thing to be judged is if she is a woman at all. You know this too Apa.”

Sati just said ‘Ah!’ in real pain.

Saroj was startled.

This girl reacted by trampling on everyone twice in this brief period of time. Why?

Aloud he said, “You are more attractive than me, Hena. Come, let’s sit in the office room.” She reminded him of his own younger sisters. He hadn’t seen them for a long time. After leaving home in ’68, he had briefly seen them a few times but they had never had a good conversation. Saroj would arrive at night and leave before dawn.

Sati was twenty-six or twenty-seven. Three or four years younger than Saroj. Besides the usual pleasure of meeting two pretty girls, Saroj had no other strong feelings yet. He didn’t know the details of their family. Already fifty or sixty thousand refugees had arrived in that small town. More were joining every day. The town had an air of festivity in daytime, but gunfire could be heard all night long. Occasionally there would be some rumors, some excitement. Occasionally the Muktibahini folks would catch some betrayers and would take them to the riverbanks to finish them off. The latest rumor was that a battlefield would be set up very near, at Hily. Late at night armored vehicles would go in that direction. Even among all such terrible happenings were these two beautiful women standing there looking at him!

Saroj tried to lighten the atmosphere by changing the topic. He said, “I’ve found a place for you. The floor is cemented but the roof is asbestos. Three rooms, a kitchen, a well, latrine all surrounded by a wall. Separate from others. I think you’ll like it.”

Sati said, “Let’s go right now! I can’t stay in this hellhole for even a minute more. See how filthy everything is!”

Hena said, “What’s the point in seeing, Apa? Let’s just go. But before that, listen to the figure for rent. You are acting like you already got a trunkload of the looted money from Habib Bank.”

There was a rumor in town that, across the border, some banks had been looted, and that the money had been brought here and into the surrounding area. The rumor mongers were guessing who the claimants were, and which political party, police or military. The town had been rife with speculations for the past week.

Saroj said, “The rent is one hundred. Couldn’t bring it down anymore.”

Sati said in despair, “One--hundred?”

As the population increased, so did the house rents. Besides, this town didn’t have many rental properties. People were renting even the courtyards and verandahs.

Hena said, “Why are you surprised, Apa? The house we saw just now shouldn’t be more than twenty-five rupees in normal times, but now they are asking for seventy-five. This is how it’s calculated—if demand is so many times higher, the rent should go up that many times too, but then it would be too high for most renters, so they just set it to double. On top of that, we are Muslim, so increase the rent some more. That’s how it became seventy-five.”

Sati said, “Would you stop it, Hena?”

“Why? Ask Sarojbabu if I am right?”

Saroj smiled, “You are totally right. Even before all this mess, it was hard for a Muslim to rent a house. Even for Muslim government workers. This town had almost no Muslims.”

Hena interrupted, “Yet there’s a huge mosque. The land is at least fifteen-twenty kathas. Undoubtedly, there were many Muslims here before the partition.”

“Of course.” Saroj smiled. “But why have you made me the opponent in your litigation?”

Sati said, “There! Serves you right! Talking nonsense all the time.”

Saroj said, “No, no. She is right. Here, people think only the Hindus got ousted from their homes. They tend to forget that as many Muslims were driven out of here, too. But we shall keep that in mind. Won’t we?” He smiled meaningfully.

Hena said, “Fine. I hereby release you from your role as the defendant. Now, pray tell, can we move in right now? We have hardly any luggage. We can move in right away.”

“Not right away. The owners are still there. You can take possession after they vacate it tomorrow. But you need to meet him and have a talk. Also, pay a hundred as an advance.”

Sati said, “I already have the money with me. Let’s go.”

10.

If anybody tried to force him to take a nap in the afternoon, Saroj wouldn’t be able to sleep that night. This started happening in his childhood when he was six or seven. Other kids –seven or eight siblings and cousins –next to him would fall asleep on the wide bed that almost filled the entire room. On one end of the bed would be his great-aunt Nalini, his father’s aunt (grandfather’s sister), who returned to the family after being widowed at fourteen years of age. She didn’t have a child of her own, but since then, she remained the head of this large joint family. Not just the head but the supreme authority in all aspects. All the hopes and ambitions of her brother’s family had merged with her blood so completely that it was difficult to separate them. Not just that, she would carry them forward in the form of fables and stories, and slip them into the memories and dreams of the sleepy, unformed boys and girls. On those nights, Saroj too would lose himself in the flood of Nalini’s storytelling. Nalini would unfold all the tales of her generations, careful not to let a single detail of hopes, ambitions, and grievances fade into oblivion. How the forests were cleared to make farmland, how they gradually acquired all the land, houses, elephants, horses, ponds and lakes, temples, mosques, grain silos, boats, trees, and other plants, how they owned neighboring washermen, barbers, potters, and blacksmiths—all those stories. Also, how various partners and part-owners arrived to lay their claims, those stories too. Even before them, about the foreigners, the sahibs, seths, and sheikhs, how the ocean flooded them, wiped out the towns and villages, farmland, people, and animals. In between, she would insert stories of the concubines of the sheikhs and sahibs, Sona Bibi’s tales, lovers of loose-haired Dechhelba, Parulbala becoming Suttee, the punishments of the great sinner Saralabala, re-marriage of widow Shashimani—what a scandal!-- the snakes, tigers, and crocs of Sundarban, and many, many such stories. Nalini herself wasn’t sure how all these people were part of her family, but she knew they were related in some ways.

They lived on the southern edge of East Bengal, barely twenty miles away from the sea. Yet Saroj never saw the sea until he turned thirty. His grandfather had seen the ocean. He owned a wooden house which served as his health resort in a village named Sohagpasha, right on the seashore. The building was actually once an office. The posts, beams, and joists were strangely shaped—just enough to do the job and make a habitable house. Saroj’s grandfather, Amiyanath, inherited the land from some ancestor and discovered the ruins of a Mughal-era shipwreck in the dense jungles. He fell in love with whatever survived of the ancient deck, the mast, and the posts for the sails. The ship must have been unmoored from its berth, pushed inland by a flood, and gotten stuck. Amiyanath cleared the jungle and built the house from the ship's timbers.

Amiyanath’s many odd habits became the stuff of the family saga. He wasn’t interested in looking after the family business. He became a disciple of a guru-like man who left the Brahmo Samaj for unknown reasons and returned to his own religion to form his own group. Perhaps Amiyanath wanted to see everything and establish himself as an honest spiritual man. That was the demand of his time. He left the noise and crowd of his double-storied house in his ancestral village and chose to live in the wooden cottage. He liked to write devotional poems and attracted followers from near and far. He used to get crates of Brook Bond tea, and tea lovers of the neighborhood villages would visit him to sip tea and discuss spiritualism. Thus, he wanted to step away from his forefathers’ stormy, perilous lifestyle. People called him a sadhu, but his wife Sharat would turn up her nose and say, ‘Ha! I’ve seen many such sadhus!’ Saroj hadn’t seen her.

Is there ever a husband whose claims are completely accepted by his wife? But Amiyanath’s fame as a ‘sadhu’ had spread far. Some even talked about his supernatural powers. The foundation of his cottage was quite high. The yard with flowering and fruit trees was fenced and had a couple of deer, like the holy ashrams of the Rishis. Even a poisonous snake basked in the sun before going into hibernation. Amiyanath sat and watched it. If anybody approached him, he would tell them to wait outside.

“Step away. Let him go first.”

He would clap his hands and direct the snake to move away. In those days, nobody questioned if a snake had ears. Snakes and humans had a daily relationship. Once, his pet deer shoved him to the ground with its antlers. While lying on the ground, he held with his weak hands onto the antlers and tried to call his servant. His only son Nikhilnath came to his rescue.

“Let go father.”

“You won’t be able to hold him back. Call Nabin.” He said weakly.

Nikhilnath was a hale and healthy man of thirty-five, father of four or five kids. He held on to the antlers and said, “Let go now.”

In the evening, his wife, Sharat, came to visit. Nalini had brought her, holding her hands. She alone took the full responsibility of looking after her older brother. She respected him like a god. His wife visited him only occasionally. Occasionally, he saw her around the main house, which was only three hundred yards from the cottage. Sharat was blind and didn’t need to come to the courtyard in the front, and Amiya couldn’t see her if she was in the backyard. The awful famine of the ’50s was two years behind. Their joint family was prosperous and at peace. Loneliness wasn’t an issue in those days. Meeting one’s husband and/or wife once a month was quite natural.

“Nabin took back the milk. Stomach upset?”

Amiya sat with his eyes shut. He was often meditative, thinking about God or poems, which for him were only next to God. He opened his eyes and said, “No.”

Sharat sensed slight rudeness in his ‘no’. Since becoming sightless, her other senses had become more acute. She hadn’t been so alert when she had her sight. Once she was sleeping with her long hair hanging from the bed. In the summer afternoon, when the world was dozing quietly, a large monitor lizard from the jungle next door entered the room and, finding nothing else, ate up almost half of her long hair. Sharat was still unaware till a maid screamed and rescued her. Her beloved long hair was half gone.

But such things never happened after her blindness. She didn’t even need any help to get around inside the house and do her chores.

“Did the milk get cold?”

“No.”

Amiyanath was seventy-five, yet sometimes a childish obstinacy got hold of him, which he wasn’t even aware of till it came out.

Sharat was surprised and tried to find the cause. She was six years younger than Amiyanath. She had long ago handed over the household duties to Nalini and her daughters-in-law. Did Amiya still expect her to look after everything like before? Keep everything well controlled? A few days ago, one young bride, her nephew’s wife, had managed to cool the boiling milk by blowing on it. This insignificant act came to her notice as it was considered unhygienic in her family. She was strict in the cleanliness of her religious rituals. This is what happened when one promised to stand in still water all her life. Amiyanath too spent the last sixty years like this. Any hassle regarding the assets and wealth was managed by his youngest brother.

Sharat said, “The deer is an adult now. Do you realize? He needs a mate. Send him back to the Sundarban.”

Now, Amiyanath looked at his wife fully. He hadn’t seen her closely for a long time. Even without sight, Sharat knew he was looking at her. He was an unruly lover. Sharat still remembered, even if Amiya did not. Nalini had released her hand and was standing on the verandah. Amiya looked at her too. Then said, “Yes, that’s true. Tell Nikhil to take him by boat to the jungle near Sohagpasha.” But immediately he felt an emptiness in his heart and, remembering a similar story in the Mahabharat, tried to control himself.

He had filled four hefty notebooks with quotations of spiritualism, prayer songs, and devotional poems. He wasn’t even aware of when the World War started and when it was over. Nor was he interested. When the deer fell him on the ground, he looked up at a group of planes in the sky. This was the third time he noticed the planes. He wasn’t concerned about the deer hurting him, but those mechanical birds in the sky had filled him with unknown dread.

A few days later, Nikhilnath told him, “Do you know India became independent last night?”

He didn’t know. Suddenly, he was confused. Two days ago, the deer was taken away by boat early in the morning. He usually sat in meditation at that time. Seeing the deer leave behind everyone’s backs, he felt overcome with grief. He couldn’t concentrate on meditation. Tears made his beard wet. Why so much pain? There were tigers around Sohagpasha; he was worried about that too.

Nikhil’s announcement turned his mind away from the deer. He immediately remembered Manindra, the son of his kinsman Shachindra. While dividing the property, Shachindra had claimed the house in town. He adored the sahibs. Before his death, he was awarded the title of Raybahadur. He occasionally visited the village for festivities but always spoke of worshipping the sahibs rather than God. It would be more helpful in this life, he thought. Amiyanath wasn’t into religious festivals either. All he needed was the mantra his guru gave him. But he didn’t object to others in the family observing such rituals. Just before Shachindra died, his son Manindra was arrested in a bomb attack and was exiled. Amiyanath was very fond of smart, good-looking Manindra. The boy was also very emotional. Exactly the opposite of his father.

“Would Manindra be released?”

Nikhil said, “For sure!”

He also added, “But sadly, the country is divided. Our district is in Pakistan.”

Amiyanath looked at his son, frightened. Twenty years ago, in Faridpur, while celebrating the birthday of his guru, he had experienced the religious riot between the Hindus and Muslims. He had never forgotten that gruesome experience, that crazed violence on both sides. He was pained to see even his non-violent Vaishnavite brethren caught up in the craziness. There were riots in Kishoreganj, Dhaka, and Barishal. Even though he didn’t get much news from the outside world, he did hear about the recent riots in Calcutta, Noakhali, and Bihar.

“Will they allow us to stay here?”

Nikhil stayed silent. The hatred had reached a point where staying in place was impossible. But where could they go? They had no other property anywhere else. After selling the property here, their share wouldn’t be enough to provide for them for even six months.

“We’ll have to leave our forefathers’ land?”

Amiyanath had tried to keep himself away from such problems. Perhaps he calculated that the short time left for him to live could somehow be spent here.

He only lived one year in independent Pakistan.

Nikhilnath wasn’t an enterprising man. He was smart and compassionate but not wise. Whatever emotion he felt about giving the news to his dad soon evaporated. By then, his first wife had died, leaving three children. There was an epidemic of beriberi at that time. Three people in the family fell victim to it.

His second wife, too, had borne four children by then. After the famine, most family members moved to Calcutta and found jobs to survive. The only exceptions were Nikhilnath and his cousin Shashankanath. They were close and had studied together in Calcutta. Beyond academics, Calcutta interested Nikhil in theater and football. Both got married during their first year of college. Soon after, Nikhil left his studies and came back home to settle. Like his father, he avoided any work related to their estate and handed over all responsibilities to Shashanka. For some time, he was crazy about the theater. He would erect stages and show various plays. He wasted a lot of money staging Shakespeare, Ibsen, and Bernard Shaw. Then he quit all that and decided to spend time with wheels, rods, and baits.

In the meantime, his oldest son got involved in Shambhu Mitra’s theater and the communist party in Calcutta.

11.

The asbestos-roofed house that Saroj had found for Sati and her family was a five to seven-minute walk from the bus stop. The house was owned by a man who depended on agriculture. Saroj knew him through Atashi and Krishnapriya. Krishnapriya owned fifteen or twenty bighas of land in a village named Basudebpur. It was mostly used in cultivating paddy. Santosh Mandal, the owner of Sati’s new house, was one of his prosperous farmers. Santosh was hired to cultivate Krishnapriya’s land. There was no one else to look after the land, so they had to rely on Santosh. He sold the paddy and paid Krishnapriya the money. Basudebpur was fifteen miles inland from Majher Bondor. One had to walk a good distance even after a bus ride. Three bighas of the land were recently sold off by Krishnapriya. Saroj had gone to Basudebpur to do the paperwork. That was when he came to know Santosh.

Santosh Mandal stayed mostly in Basudebpur, looking after his farmland. His wife stayed in the house in town with their school-going children. During the holidays, they went back to their village. Seeing the war situation and the state of the town, Santosh had decided to take the family to the village. Also, the school was closed for an indefinite period. Because of Saroj’s special request, Santosh agreed to rent the house to Sati. He was also worried about leaving the house vacant, in case the squatters occupied it permanently or stole the furniture, including the doors and windows. A few houses in the neighborhood had already been forcibly ‘rented’ this way. So, this arrangement was a win-win for both parties.

Sati and Hena both attracted Saroj in different ways. Sati’s downcast but compassionate character kept Saroj very conscious about what he said. He was a bit reserved and always on his best behavior with Sati. Yet he loved her calm, serene personality very much.

Hena was totally the opposite of Sati. So, Saroj was talkative with her too. Hena spoke as she thought. And she didn’t take too long to think before speaking. She had a childlike arrogance but also a sharp intellect. Saroj couldn’t understand why she was against everything that screamed establishment. She would attack any ideology, any person, whether family or not, always prepared with suppressed excitement to strike someone or something. She needed no preparation. It was against her nature to wait for something to happen. Her family was rather afraid of her. Hena had all the characteristics of a dictator mentality, and Saroj was afraid she would infect him with it. With Sati, he felt self-controlled; with Hena, for the opposite reason, he was terrified yet entranced.

After settling into the new house, Sati invited Saroj for tea one day. That’s when Saroj got to know Abdul Kuddus properly. Even though they couldn’t bring enough money across the border, they did bring some gold jewelry in secret. One by one, they started selling them. For that, they needed Saroj’s help and cooperation. Saroj was surprised to find himself gradually getting enmeshed in an opportunistic tangle with this family. He didn’t know what he could gain out of these grossly self-interested transactions. This made him uneasy, but he saw no way out of it. Still, his conservative, middle-class mentality balked at the situation.

Abdul Kuddus wore extremely loose pyjamas and a long panjabi-shirt. Both were old and worn out in places.

Sati introduced him, “My mother’s brother.”

Hena jumped in her typical style before Sati could finish, “Abdul Kuddus—communist, poet, nationalist. But not clear now if he is a follower of Moscow or China, Trotsky or Che.”

Saroj told Sati, “I did meet him once before.” Then he turned to Hena, “And you? Who do you follow?”

Sati said, “She is a true Maoist. Pure gold-- communist revolutionary.”

Her voice had some intolerance mixed in it.

Kuddus extinguished the flare-up between the sisters, “Is Saroj from West Bengal? I mean, your forefathers are from here, too?”

“No. Like you, my ancestors are also from your side. We came here in the ’50s.”

Kuddus laughed, “That means, both of us have been uprooted.”

“There you go. Now start talking about your motherland to your heart's content.” Hena said. “Let the competition begin as to who had larger land and who had elephants tied in his yard.”

Saroj jokingly said, “Has this bad habit also afflicted people who migrated from here?”

Hena pretended surprise, “Bad habit? How can you call it a bad habit? Do you know my uncle’s house had a mammoth tied in the yard?”

Sati reprimanded, “Hena, stop being childish.”

Hena’s exuberance was suddenly turned off. She flashed an angry look at her sister and walked out. Obviously, she felt disgraced. Suddenly, she stomped back in, telling Sati, “Shut up and don’t teach me!” Then she stomped out again.

Sati was hurt but tried to laugh it off in front of others. Her fading smile held both indulgence for Hena and contrition for her own indiscretion. In fact, no one appreciated her unnecessary scolding. Henna was most definitely not a child.

“Let me bring the tea for you,” Sati said to lighten the atmosphere.

As she left, Kuddus said, “These two sisters love each other yet fight all the time. Even here, they can’t stop. Just look at them.”

Abdul Kuddus was born in Bardhaman. He spent much of his childhood and early youth in India. Then came the partition, and his family left to look for homes in Khulna, Dhaka, and Chattogram. Where was his home? Abdul still hoped for some sort of revolution. He considered Sati and her father (who had been missing since last March) to be simple-minded in politics. He was enlisted in the Awami League, the most opportunistic political group. He believed in the ascendance and popularity of opportunism.

Most people had a tacit conflict with rules and regulations, law and discipline. These took away one’s personal freedom, said the first lesson in politics. A lawless, unruly person would justly be criticized by others, but at the same time also sympathized with by them. He knew that he, too, was a potential sacrifice. That was why the Awami League, or the Congress party, which was more relaxed in this regard, received more popular support than the Communist Party. For this reason, the communist parties had now loosened their rules and disciplines worldwide, and in the ’60s this created polarization within the parties. The Naxal movement in this subcontinent was the direct result of these changes. Kuddus said all this with the childish pride of an irrefutable logic.

Sati had gone to get the tea. Hena was sitting outside on the veranda, still sullen with Sati’s rebuke or her counter-rudeness. She got another chance to vent her heat at her uncle’s commentary and asked from outside, “Is Sarojbabu a communist also?”

“Are you suspecting me?” Saroj asked with mock trepidation.

From Kuddus’ friendly tone, Saroj had wondered how much Sati had revealed about her family to him. He was amazed to detect no trace of worry or terror about this, as he would have felt before. Subconsciously, he realized that being at ease was the right thing to do at this time. Any kind of uneasiness would provoke suspicion.

Hena spoke out with surprising maturity, “This foreign country… one that was a complete enemy of our country till very recently, and there is still no reason to consider it otherwise… the way uncle is talking to a citizen of this country is making me worried.”

Saroj was impressed by the speech of this young girl. He had not thought that an impatient, talkative, young girl could talk so logically and convincingly. She had a surprising blend of personalities. She again said, “But Sarojbabu, the truth in uncle’s idea is very old. Now in our countries, the communists are as bad as others. Besides, their egotism and ruthlessness are unparalleled.”

Even though Saroj couldn’t see Hena from inside the room, Abdul Kuddus could see her, and he looked at her affectionately.

But the reaction to her speech was mixed. Saroj was affected by her quickness and acuity. He could feel an opposing reaction building within himself. This girl was carelessly blowing away the ideas he had earned with blood and sweat over a long period of time. How much experience did she have? She was perhaps just trying to get back some face lost by her sister’s rebuke.

Saroj said, “If ever the communists come to power in this subcontinent, I will look for the proof of your sentiment. But, so far, nothing like that had happened.”

Hena stood up and came to the door; her nostrils flared. Saroj understood only later the reason for her sudden excitement.

Kuddus said, “Come, sit down, Heni, then speak.”

Hena didn’t sit. She said, “I don’t know what you mean by ‘coming to power’. But if we can hold power over five villages, or even one village---”

Kuddus gently interrupted her, “But Heni, people act differently during wartime than when they are at peace.”

“Exactly, I agree. But the difference in the ideology does not affect their actions.”

Kuddus softly said, “But Heni, if we believe this, we have to negate the entire past of socialism.”

With barely suppressed emotion, Hena replied, “Why the past? Negate our entire future, too. Only after bayonetting seven soldiers to death, I understood what I was doing, what they were trying to make me do.”

She quickly turned away to exit and collided with Sati, bearing the tea tray. The next moment, she screamed and fell on the ground like an axed banana tree.

Saroj stood up in alarm. Abdul Kuddus got off his seat. Hena was mourning and thrashing her entire body, scattering everything around.

From his experience, Saroj recognized Hena’s epileptic attack. But he had never seen such a severe one before. Sati and her mother tried to hold her down but were more concerned about her modesty than any injury. Saroj stepped outside.

- 1 | 2 | 3 | 4

- মন্তব্য জমা দিন / Make a comment

- মন্তব্য পড়ুন / Read comments

- কীভাবে লেখা পাঠাবেন তা জানতে এখানে ক্লিক করুন | "পরবাস"-এ প্রকাশিত রচনার দায়িত্ব সংশ্লিষ্ট রচনাকারের/রচনাকারদের। "পরবাস"-এ বেরোনো কোনো লেখার মধ্যে দিয়ে যে মত প্রকাশ করা হয়েছে তা লেখকের/লেখকদের নিজস্ব। তজ্জনিত কোন ক্ষয়ক্ষতির জন্য "পরবাস"-এর প্রকাশক ও সম্পাদকরা দায়ী নন। | Email: parabaas@parabaas.com | Sign up for Parabaas updates | © 1997-2025 Parabaas Inc. All rights reserved. | About Us