-

পরবাস

বাংলা ভাষা, সাহিত্য ও সংস্কৃতি

Parabaas, a Bengali webzine since 1997 ... ISSN 1563-8685 -

ছোটদের পরবাস

Satyajit Ray

Rabindranath Tagore

Buddhadeva Bose

Jibanananda Das

Shakti Chattopadhyay

সাক্ষাৎকার -

English

Written in English

Book Reviews

Memoirs

Essays

Translated into English

Stories

Poems

Essays

Memoirs

Novels

Plays

The Land Where

I Found It All-

পুত্রবধূর চোখে গৌরী আইয়ুব এবং প্রসঙ্গত

-

বিশ্বের ইতিহাসে হুগলি নদী

-

বেদখল ও অন্যান্য গল্প

-

Audiobook

Looking For An Address

Nabaneeta Dev Sen

Available on Amazon, Spotify, Google Play, Apple Books and other platforms.

-

পরবাস গল্প সংকলন-

নির্বাচন ও সম্পাদনা:

সিদ্ধার্থ মুখোপাধ্যায়)

-

Parabaas : পরবাস : বাংলা ভাষা, সাহিত্য ও সংস্কৃতি -

পরবাস | English | Story

Share -

The Haunted Mine : Sailajananda Mukhopadhyay

translated from Bengali to English by Santanu Banerjee

A doctor of medicine by profession, my job was always full of challenges. From ordinary labourers to managers, all the employees seemed to depend on me for their lives and well-being. As if I controlled their fate. If someone had a small injury on his leg, he called the doctor. If any sick person had breathed their last inside any hovels, the doctor would be summoned again. A coolie had died inside the mine – I must rush to the place before anyone else would turn up. Anyway, there was no point in feeling bad when one had decided to accept this profession.

My residential quarter was not bad: two pairs of rooms covered with a tiled roof. There was a slightly raised terrace in front of the rooms. And just beneath it was a courtyard where cooking was done.

There was plenty of open space on all sides. Initially, I thought it was a good idea to come to this place. The previous colliery I had worked at was huge, almost the size of a small town. There I was choked by smoke, and there were slums in all directions. Here at least, I could breathe a little clean air.

The manager of this colliery was a Bengali gentleman, an amicable person. Since I was new at this place, I had to make his acquaintance. I visited his bungalow during my evening walk that day. A pot-bellied, short, dark man suddenly stopped before me and greeted me with a namaskar. His moustache was hanging down to his lower lip, and he wore a spectacle with a white nickel frame on his nose. He looked sternly at me for some time and then asked, "You are the new doctor, right? I am, in fact, the head clerk.”

I did not know how to reply. Nodding my head and managing a faint smile, I too greeted him back with a namaskar and started on my way. But the man followed me. He said, “Do you mind walking with me that way for a while? I have something to discuss with you.”

While walking, he began to talk about himself. He had been working here for nearly a decade but never absented himself for even a single day. His home village was about a mile away. He went home every day before dusk.

I had not asked him anything, yet he started warning me, “See, this is the sort of rule here. Never get out of your residence after dark! You are new here. I caution you as you know little about this place.”

“But why?” I asked.

Immediately his reddish teeth stained with betel juice peeped through the bushy moustache. I realised that it was a smile.

He replied, “You should not ask this question. This is a horrible place! Do you believe in ghosts?”

I answered him in the negative.

“Damn! Here ghosts are everywhere. The entire colliery is densely populated with ghosts. You would not find a single human figure here in the evening. People are afraid of getting down into the mines, even in the daytime. And all activities cease after dark. At night you will come across weird things. From your residential quarter, you may hear engines rumbling, sounds of digging, and the roars of coal wagons pushed along the tram lines. But go near, and you will hear nothing! You will see nothing happening. In the evenings, you may not find any coal dust in the depots, but in the morning, you would see four to five wagons, fully loaded with heaps of coal."

I said, “It sounds good. After all, the ghosts are so helpful here.”

The gentleman exposed his teeth once again in a smile. He replied, "Say what you may, but people are often seriously wounded or even killed here. Not a single month passes by without some people getting murdered. Earlier, everything happened inside the mines. But the ghosts have all come out in the open for the last six years. Do you know what happens to the registers and papers in my office? I may put them under lock and key today, but come tomorrow, you will see everything disorganised, topsy-turvy, all messed up. But they do not destroy anything; that must be granted, and we all have become used to it."

I smiled and asked, “Is that why you try to reach home before dark?”

The man nodded and said, "Certainly, you will quake in fear if I start telling you what happened the other day. But I am already late for home. I will tell you all in another meeting. See you then. Namaskar." Bidding me goodbye with his folded hands, he suddenly turned right and walked out of view.

I had a long conversation with the manager on that day. I asked him, "I hear

about ghosts in your colliery. Is it true?"

He laughed, "So, you've heard already?"

"Yes, of course, I have heard. But do ghosts really exist? I never believe in them.”

"You must not take it seriously," replied the manager, adding, "But the condition of the mine is not good. Ceilings hang loose. People must be extremely cautious while digging coal or some slab may crash and cause fatal injuries. Some years, no, actually many years ago, before I was appointed here, the Singharon river had flooded dangerously. The water level rose so high that it reached the pit's opening. Water flowed down inside the mine through the chanok. Who could stop the flow? It was daytime, so mining activities were going on in full swing. It took a lot of effort to save the people. Water had been flowing in all the while until the flood stopped on the third day. Then, the entire mine was filled with water. After pumping the water out and getting down to the bottom with great difficulties, almost fifty people were found dead. From then on, it is believed that ghosts must surely be infesting a place where so many people had lost their lives.” Again he giggled loudly.

Though I laughed as well, I thought, "Alas! So many human beings were drowned crying, in vain, to be rescued! Some of them might have had aged parents in the hovels waiting for their return, some perhaps their sons or daughters, wives or husbands. Alas!" My smile faded from my face – I could see the tragic scene in front of my eyes.

The evening thickened while we were talking. The manager's servant came and placed a lantern near us. I was about to take leave when he requested, "Have some tea." When I finally left, it was eight already.

The manager said, “My servant would accompany you back to your place with a lamp.” Perhaps he thought whether I would feel troubled by the ghosts. I smilingly assured him, “That is not needed at all. I am really not afraid of ghosts.”

He then happily bade me goodbye with a namaskar.

As I crossed the main gate of his bungalow and came out on the road, I noticed the hushed darkness. I could not hear any noise of human presence around. I looked up into the sky full of stars and moved forward in their dimmed light.

My quarter was not very close. I had to cross two or three slums to reach an orchard of mango and jackfruit trees and then take another path made of packed coal dust. A dilapidated house stood a little distance from where I had to turn right to pass under a neem tree and stroll a couple of minutes further to arrive at my door.

I cannot recollect right now what I thought as I walked down the narrow path when I heard footsteps behind. A dog suddenly began to bark at the hovels I had just left behind. Hardly the noise had stopped when a tall, dark figure landed in front of me, crunching the dried leaves under the trees. I was startled and a bit afraid. Before I could ask the man any question, he came closer and pleaded, "Doctor, please come along with me." Perhaps the man was a Santhal.

“Why, what happened?” I asked him.

“You have to save my son, doctor!” He replied, “If you refuse to come, he would certainly die. Come with me, please!”

“What happened to your son?”

“No idea,” he said. “You come and see yourself. I will bring you back to your home.”

His voice sounded as if he would break into tears. I could not say no. "Let's go," I replied.

Crossing the orchard, we took another road. The man was walking in front of me. I asked him, "What is your name?"

“Tuila Majhi.”

“How far do we need to go?”

He pointed with his raised arm, “Right there.”

Since it was impossible to walk silently, I tried to start a conversation, “Do you dig coal inside the mine?” “Yes, Babu.”

“How many sons do you have?”

“Only one.”

“How old is he?”

“He is grown up now.”

“Yet – what exactly is his age?”

“Who knows? I have no idea.”

We were walking while talking to each other.

The coolie hovels he had pointed out to me earlier seemed to recede farther away as we walked.

I inquired, “Why Tuila, you said it is very near?”

Tuila answered, "Indeed, Babu. Don't you think it is close?"

Nevertheless, the path seemed unending. To pass the time, I started talking again, "What happened to your son?"

Tuila remained silent.

“Tell me, what happened to him?”

This time, he seemed irritated, "The whole mine was flooded."

Flooded! At once, I recalled what the manager had told me about the flood. I said, "When did it happen? Many years ago?"

Tuila replied, “Yes, many years.”

“Then?”

"Then there were so many of us inside the mine, all digging up coal."

I questioned, "But none returned alive from there, I have heard. How are you still

living?"

No answer came from Tuila.

A strange feeling gripped my heart. I said, "Tuila, I was told that people here are afraid of ghosts. Is it true?"

Suddenly I found Tuila nowhere around. First, I thought he had moved ahead of me, and I could not see him in the dark because of his dark complexion. I called out aloud – "Tuila! Where are you, Tuila?"

I looked back and forth at the left and the right, but I failed to trace him anywhere. I heard only the hedge crickets singing. My head reeled, and the blood in my veins turned into water.

I could not remember how far I walked, which way, and how long. I was walking till the darkness dissipated by the light of early morning. There was no energy left in my body, no strength in my legs. I was only alive because I had not died – that was my only impression. Seeing some people coming toward me at a distance, I sat down on the roadside. But I could hardly trust anybody anymore. Weren't they all ghosts?

In the early light of the day, I saw a small group of coolies going to the colliery, carrying baskets and axes. I asked them, "Domorna, which way?”

One of them replied, “You think it is here? Look there, far away, see the

chimney?”

What a disaster! When I reached home, I walked three miles, completely exhausted and nearly dead. I saw the wails and worries writ large on the faces of my family members. Neither my daughter nor my son, not even my servant, had slept throughout the last night. This was a place new to them. They had no clue how to get help. Depending solely on God's will, they waited for me while looking eagerly toward the road.

Lest they be afraid, I disclosed nothing to them, only informing them that I had to spend the whole night at the bedside of a seriously ill patient. Soon after, I applied to the company’s head office for my transfer and was waiting for a reply when another accident took place.

It was almost one o'clock at night. I received a call from the manager – someone had died inside the mine, and I must visit the place. I replied to the messenger that it was impossible for me to move. Let the manager be requested to come to me. Very soon, he came, with a couple of servants, all carrying torches. He asked me with a characteristic smile, "Afraid of ghosts?" I had not told him about that night's experience with Tuila. In fact, I was ashamed to tell him about it. I replied, “No, not exactly. But nobody works here inside the mine at night, right? Then how can someone die?”

The manager explained. "Some coal was urgently required, so we offered them drinks and doubled their wages. I have informed the police already. Before they reach the place, we must go there and check ourselves."

We cautiously went down into the mine with a group of people. The coal was dug in the opening of the seventh kanthi. The man died right there while a slab had fallen on his skull. His companions all went up to get help, leaving the body. Yet when we reached, there was no trace of the corpse. We took the Sardar of the coolies with us and, with many torches and men, started searching for the dead body. After almost an hour's effort, we found the corpse smeared in blood in the middle of a huge 'goaf'. There was hardly any possibility for the dead body to be carried there. We brought it back near the seventh kanthi and climbed back up. There was little chance to take it outside the mine until the police could make their visit. But none of our men agreed to guard the body even after being promised large rewards.

The manager himself accompanied me to my quarter. But I was to get down once again into the mine along with the police force.

I could not recollect the exact time at night when the police arrived. We went down the mine again, this time with fewer people. A lot of men did not agree to come with us. The manager laughed again and said, "The cops are going with us; what is there to worry about? Even the ghosts are afraid of the cops."

I smiled despondently and went down. Be what it may in my lot. The darkness of night was added to more darkness in that netherworld of black coal. It was dark everywhere. But this time, we had more than sufficient light with us. Each one of us was carrying an acetylene lamp. The police inspector was also equipped with his flashlight.

We were all following the Sardar, but waiting for us was a strange sight!

Again, the corpse was missing. Only some blood had pooled thick upon the black coal. We looked at each other in silence. Only the noise of small coal pieces dropping here and there mixed with the sound of dripping water. We hardly knew what to do!

The inspector said, "I cannot trust my eyes. Come, let us find the body."

It was indeed unbelievable. How could the same thing happen again?

We began searching. The inspector was a courageous man. He led us with a torch in his hand, casting light ahead.

I was afraid to stay at the back. Somehow I did manage to pass others and went in the middle of the search team.

Even after much searching, the corpse was not found.

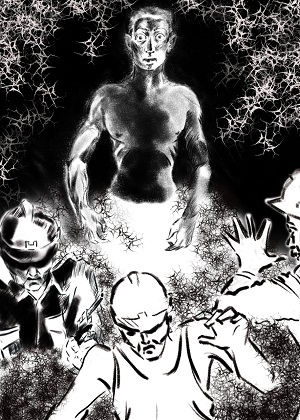

While passing through a narrow tunnel, we heard a loud scream. It was the sound of someone hurt in a serious accident. The cry came from a place near the inspector. We all shuddered and tried to walk back hastily, colliding with one another. I was so afraid that I could only hold the manager tightly. My hairs stood on end as I shivered in fear. We were doomed, and there was little hope for a rescue.

The inspector bravely focused his flashlight and found himself standing on the corpse's chest.

“Oh my god!” He suddenly leapt on me. I fell on the manager at once, and he, in turn, stamped the feet of a constable. While we were busy disentangling, the inspector's flashlight went dead. Even after pressing the switch several times, it could not be lit. Then the lamps in our hands too were strangely extinguished one by one.

There was no hope for our lives!

Standing motionless in the dark for some time, we finally decided to light matchsticks and go up by grabbing onto the tunnel's walls. Escape was the only option besides losing our lives!

The Sardar proposed, “I know the way out. Give me a box of matches.”

I had one box in my pocket. With trembling hands, I gave it to him.

As he lit a matchstick, we saw a demon-like, dark Santhal in front of us. Stretching his long arms forward and blocking our path, he said, "Where would you escape? Save my son first, and then you may go."

The inspector had a revolver in his pocket. He whipped it out and fired. The cracking noise deafened our ears.

Immediately, we heard the inspector cry for his life, "O god! Leave me, I say. Leave me. Leave me, please. Or I will die."

It was a battle between a ghost and a human being. We heard the inspector groaning in pain. Perhaps he was dragged into a distance from us. Gradually the sound of his gasps and struggle stopped. We heard the angry voice of the Santhal, "Would you fire anymore? Come on; let me see what a man you are?"

At that moment, we were all tightly holding one another and shaking in fear.

"You had drowned me in flood like a rat. My son was alive, but you killed him too." Saying this, Tuila turned towards us and asked, "Where is your manager?"

The manager started to weep and pray for mercy, "Please spare my life; I am

not guilty."

"Fine, I am leaving you. But where is the doctor?" Saying this, he caught hold of

my neck and shouted at me, "Come, let's see if you can survive."

I was almost choked by then. Unable to speak out, I could only whimper in pain and fear.

I did not know how I came back alive.

Since I had placed an application for transfer, I decided to visit the manager to see whether any reply had arrived. After reaching his office, I came to know that he had been strangely missing since last night. He could not be traced anywhere, either outside or inside the mine.

My God! I trembled once again. Where had he vanished?

The original story 'ভূতুড়ে খাদ' ('Bhuture khaad') is included in Sailajananda Mukhopadhyay'ys collection of short stories 'Sunirbachito Koilakuthi Golposongroho' (Ed. Baridbaran Ghosh); New Age Publishers; Kolkata, 2004. - মন্তব্য জমা দিন / Make a comment

- মন্তব্য পড়ুন / Read comments

- কীভাবে লেখা পাঠাবেন তা জানতে এখানে ক্লিক করুন | "পরবাস"-এ প্রকাশিত রচনার দায়িত্ব সংশ্লিষ্ট রচনাকারের/রচনাকারদের। "পরবাস"-এ বেরোনো কোনো লেখার মধ্যে দিয়ে যে মত প্রকাশ করা হয়েছে তা লেখকের/লেখকদের নিজস্ব। তজ্জনিত কোন ক্ষয়ক্ষতির জন্য "পরবাস"-এর প্রকাশক ও সম্পাদকরা দায়ী নন। | Email: parabaas@parabaas.com | Sign up for Parabaas updates | © 1997-2025 Parabaas Inc. All rights reserved. | About Us