-

পরবাস

বাংলা ভাষা, সাহিত্য ও সংস্কৃতি

Parabaas, a Bengali webzine since 1997 ... ISSN 1563-8685 -

ছোটদের পরবাস

Satyajit Ray

Rabindranath Tagore

Buddhadeva Bose

Jibanananda Das

Shakti Chattopadhyay

সাক্ষাৎকার -

English

Written in English

Book Reviews

Memoirs

Essays

Translated into English

Stories

Poems

Essays

Memoirs

Novels

Plays

-

পুত্রবধূর চোখে গৌরী আইয়ুব এবং প্রসঙ্গত

-

বিশ্বের ইতিহাসে হুগলি নদী

-

বেদখল ও অন্যান্য গল্প

-

Audiobook

Looking For An Address

Nabaneeta Dev Sen

Available on Amazon, Spotify, Google Play, Apple Books and other platforms.

-

পরবাস গল্প সংকলন-

নির্বাচন ও সম্পাদনা:

সিদ্ধার্থ মুখোপাধ্যায়)

-

Parabaas : পরবাস : বাংলা ভাষা, সাহিত্য ও সংস্কৃতি -

পরবাস | Rabindranath Tagore | Essay

Share -

Universalism of Tagore: The Specificities of Portuguese Reception : Sovon Sanyal

From the first issue of India Nova (May 7, 1924)

The First World War had just been over. Europe wasn’t yet out of its stupor. Portugal was passing through one of its most turbulent periods of history. In Portugal, Monarchy ended with unprecedent violence and the king was assassinated. The country became a republic (1910), but continued to be in political instability. With the rise of new imperial powers in Europe, militarism merged with patriotism under the strong presence of the State. Man died for ideology, man was sacrificed for ideology. In peace, nations prepared for more wars. Stable government in Portugal became a dream. In the mean time fascism was spreading fast and jingoism was as common as wind. A group of sensible writers and intellectuals worked voluntarily to save the country from this spread of hydra-like heads of violence and hatred. If we say that this group of writers was busy only with the problems of their country, it would certainly be injustice. They thought that the writers must participate intellectually in the social construction and the arena of politics should not be left completely in the hands of the politicians. It was not new nevertheless. During the movement for a Republic, writers actively addressed all questions of the society together with those of literature in the construction of their society. Here one could find the influence of socialism of the nineteenth century. It was sheer coincidence that Tagore was introduced to Europe immediately before the First world War and his message of love and compassion and universal unity of Man was suppressed with the sound of war drums. Tagore was introduced to the Portuguese readers in fact in the same year of the war.

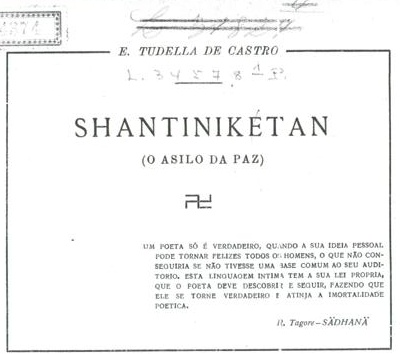

Lecture on Shantiniketan

Tudela de Castro, a Portuguese scholar, delivered on 11 May, 1923 a lecture at the Theosophical Society of Portugal on Shantineketan, that is, Tagore’s university which is an expression of the ideas of self-reliance that he strongly advocated for his countrymen under the foreign rule. In his lecture, he read this translation of the poem “Where the mind is without fear...”

Lá, onde o espiritu está sem receio e a fronte erguida;

Lá, onde o conhecimento é livre;

Lá, onde o mundo não foi dividido por estritas paredes;

Lá, onde as palavras dimanam das profundezas da sinceridade;

Lá, o esforço infatigável estende os braços para perfeição;

Lá, onde a razão clara não se afastou mortalmente para o arido e triste

deserto da convenção;

Lá, onde o espirito por ti guiado se alarga na expansão continua do pensamento e da ação;---

N’ste paraizo de liberdade, meu Pae, (1) permite que a minha patria acorde.

(1) Referencia a Deus

Article with translation in India Nova

We come across another translation of the poem in the first issue of India Nova, the journal of the Instituto Indiano founded at the famous CoimbraUniversity, by Goan poet-intellectual Adeodato Barreto (1904-1936). Adeodato and his friend, a fellow Goan, Telo de Mascarenhas (1899-1979) undertook translation of Rabindranath’s works into Portuguese. In fact, it assumed a very special significance in the context of passive cultural resistance offered by the native Goans to the Portuguese imperial politics of assimilation. It was the time when some Goans started questioning the political and moral rights of Portugal to hold on to their land which had been culturally a part of India. Who was the translator of this poem that appeared on the first issue (7 May, 1928)? It is slightly difficult to answer, since in that issue the translator’s name was not mentioned. The published collection of Adeodato’s writings does not mention this translation. Is it Mascarenhas’s translation? We may find out in the future. For the time being we pay attention to the fact that it appeared on the first page of the first issue of India Nova. It not only reminds its readers tangentially the absence of freedom in their political and cultural life under the military government, but also the aspirations for an inter-civilization dialogue. Both Tagore and Barreto were located in the same socio-political situation and, earnestly desired to alter it through dialogues with genuine respect and recognition for attaining higher level of universal understanding.

Lá onde a fronte se ergue aliva e

O espiritu vive tranquilo;

La’ onde o conhecimento é livre;

Lá onde o mundo se não fragmentou ainda entre estrietas e acanhadas muralhas;

Lá onde as palavras se brotam das profundas da sinceridade;

Lá onde o esforços incansável estende os braços para a perfeição;

Lá onde a corrente limpida da Razão não sofreu ainda um letal desvio

Para o arido e sobrio deserto do costume;

Lá onde espirito guiado, por Ti,

Avança para o largamento

Continuo do pensamento e da acção;

Nesse paraiso de liberdade, meu

Pai, permite que a minha

Pátria desperte !

In 1969, a translation of Gitanjali was published from Brasília. The translator is Gasparino Damata. In fact, I was, for certain reasons, extra curious about the translator, as there was, in the contemporary Brazilian literary arena, a little known social activist-writer with the same name. Anyway Gasparino realised the timelessness of Tagore’s work, though initially he argued with himself why the youth of his time who adore liberty in every aspect of life and are steeped in the pleasure of carnal love would read Gitanjali He dedicated the translation for the ‘Year 2021’!

Onde o espírito vive sem mêdo e a fronte se mantém erguida;

Onde o saber é livre;

Onde o mundo não foi dividido em pedaços por estreitas paredes domésticas;

Onde as palavras brotam do fundo da verdade;

Onde o esfôrço incansável estende os braços para a perfeição;

Onde a fonte clara da razão não perdeu o veio no triste deserto de areia do hábito rotineiro;

Onde o espírito é levado a tua presença em pensamento e acção sempre cresentes;

Dentro dêsse céu de liberdade, ó meu Pai, deixa que se erga a minha pátria.

Besides these three translations of “Where the mind is without fear...”, from time to time, its Portuguese rendering was done by the readers who felt a sort of inner urge to spread its message or simply to share it with others. Thus several translations appeared in different literary magazines and newspapers in Goa in the past century.

- এই লেখাটি পুরোনো ফরম্যাটে দেখুন

- মন্তব্য জমা দিন / Make a comment

- মন্তব্য পড়ুন / Read comments

- কীভাবে লেখা পাঠাবেন তা জানতে এখানে ক্লিক করুন | "পরবাস"-এ প্রকাশিত রচনার দায়িত্ব সংশ্লিষ্ট রচনাকারের/রচনাকারদের। "পরবাস"-এ বেরোনো কোনো লেখার মধ্যে দিয়ে যে মত প্রকাশ করা হয়েছে তা লেখকের/লেখকদের নিজস্ব। তজ্জনিত কোন ক্ষয়ক্ষতির জন্য "পরবাস"-এর প্রকাশক ও সম্পাদকরা দায়ী নন। | Email: parabaas@parabaas.com | Sign up for Parabaas updates | © 1997-2025 Parabaas Inc. All rights reserved. | About Us