-

পরবাস

বাংলা ভাষা, সাহিত্য ও সংস্কৃতি

Parabaas, a Bengali webzine since 1997 ... ISSN 1563-8685 -

ছোটদের পরবাস

Satyajit Ray

Rabindranath Tagore

Buddhadeva Bose

Jibanananda Das

Shakti Chattopadhyay

সাক্ষাৎকার -

English

Written in English

Book Reviews

Memoirs

Essays

Translated into English

Stories

Poems

Essays

Memoirs

Novels

Plays

-

পুত্রবধূর চোখে গৌরী আইয়ুব এবং প্রসঙ্গত

-

বিশ্বের ইতিহাসে হুগলি নদী

-

বেদখল ও অন্যান্য গল্প

-

Audiobook

Looking For An Address

Nabaneeta Dev Sen

Available on Amazon, Spotify, Google Play, Apple Books and other platforms.

-

পরবাস গল্প সংকলন-

নির্বাচন ও সম্পাদনা:

সিদ্ধার্থ মুখোপাধ্যায়)

-

Parabaas : পরবাস : বাংলা ভাষা, সাহিত্য ও সংস্কৃতি -

পরবাস | Rabindranath Tagore | Essay

Share -

Freedom in Tagore's Plays : Bhaswati Ghosh

Bairagyasadhane mukti, se amar noy.

Asankhyabandhan-majhe mahanandamay

lavibo muktir swaad.

My freedom lies not in

pursuing detachment.

Amidst a thousand fetters

shall I savour the taste of freedom

in delirious joy.

At various stages in his life, enriched by ever new experiences—both mystical and material—Tagore celebrates a sense of liberation. In all the genres of his literary oeuvre, the subject of freedom appears again and again—sometimes evidently, at other times in a nuanced fashion. His personal philosophy, which includes the idea of freedom or mukti, drew a lot from the ancient Indian Upanishadic texts. That and his own realizations led him to believe that true freedom does not come from the pursuit of individualism, but in the coming together of minds and hearts. At the same time, Tagore remains a staunch votary of exercising individual exploration as a key to finding freedom.

On a temporal level, Tagore uses the notion of freedom to decry narrow nationalistic boundaries, governed by myopic ambition and greed. We look at four of Tagore’s plays—Dakghar (The Post Office), Achalayatan (The Immovable), Muktadhara (The Waterfall) and Raktakarabi (Red Oleanders), which bring out different facets of his broader abstraction of freedom.

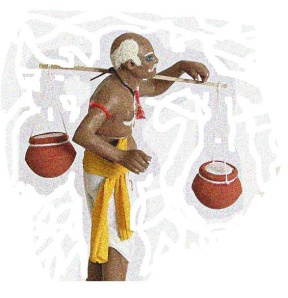

In Dakghar (The Post Office), young Amal, the protagonist, bonds with numerous strangers with the spontaneity and guilelessness typical of most children. The play cleverly unravels Tagore’s thoughts on freedom. Being ill, young Amal is confined to his bed by the kaviraj’s orders and isn’t allowed to step out of the house. Lying on his bed, he watches the world go by, as he makes friends with passersby—a curd seller, a watchman, a flower girl, and an old man.

Even though Amal is physically bound, he isn’t a prisoner in the spiritual or creative sense. His flourishing imagination, coupled with his disarming affability, connects him to the hearts of seemingly disparate people. For as Tagore writes in his foreword to S Radhakrishnan’s The Philosophy of Upanishads [1]: “When our self is illuminated with the light of love, then the negative aspect of its separateness with others loses its finality, and then our relationship with others is no longer that of competition and conflict, but of sympathy and co-operation.” Young Amal is an embodiment of the child heart that has not yet been contaminated by man-made divisions of social or economic class. Thus Amal can mingle with his fellow humans with complete ease and no sense of separation.

Even though Amal is physically bound, he isn’t a prisoner in the spiritual or creative sense. His flourishing imagination, coupled with his disarming affability, connects him to the hearts of seemingly disparate people. For as Tagore writes in his foreword to S Radhakrishnan’s The Philosophy of Upanishads [1]: “When our self is illuminated with the light of love, then the negative aspect of its separateness with others loses its finality, and then our relationship with others is no longer that of competition and conflict, but of sympathy and co-operation.” Young Amal is an embodiment of the child heart that has not yet been contaminated by man-made divisions of social or economic class. Thus Amal can mingle with his fellow humans with complete ease and no sense of separation.Amal: Honestly, Doi-walla, I haven’t ever been there. When the kaviraj allows me to go out, will you take me to your village?

Curd seller: Sure, my dear, I will take you!

Amal: Please teach me how to sell curd like you do. Carrying that long pole like you do on your shoulders—through far-away places.

Curd seller: Goodness! Why should you sell curd, my child? You will be a learned man after reading many books.

Amal: No, no, I shall never be a learned man. I will go by your red road down the banyan tree in Goalpara to bring curd and then sell it in far-off villages. The way you say it—”Curd, curd, delicious curd.” Tell me how you sing it.

Curd seller: Woe be me! Is this something to learn?

Amal: Believe me; I love hearing that. Just the way the heart feels sad when the song of a distant bird comes—when I heard your call through that row of trees on that turning, I felt as if—who knows what I felt!

Curd seller: My child, have this cup of curd.

Amal: But I don’t have money.

Curd seller: Oh no, no—don’t talk about money. I will be so happy if you took a bit of my curd.

Panchak: Listen, Subhadra, I have no idea what happens because of what. But whatever happens, I am never afraid. Freedom in Tagore’s book also means the liberty to make mistakes and learning from them. “Those in authority are never tired of holding forth on the possibility of the abuse of freedom as a reason for withholding it, but without that possibility freedom would not really be free. And the only way of learning to use a thing properly is through its misuse

[2]. Achalayatan (The Immovable) is a classic manifestation of this joy of learning from one’s own fumbling. The play is eponymous with a school that puts excessive emphasis on dry, ritualistic learning, imposed with punishments and devoid of life. Young Panchak is a misfit in this environment and doesn’t mind facing the unknown risks of his wrongdoings.

Freedom in Tagore’s book also means the liberty to make mistakes and learning from them. “Those in authority are never tired of holding forth on the possibility of the abuse of freedom as a reason for withholding it, but without that possibility freedom would not really be free. And the only way of learning to use a thing properly is through its misuse

[2]. Achalayatan (The Immovable) is a classic manifestation of this joy of learning from one’s own fumbling. The play is eponymous with a school that puts excessive emphasis on dry, ritualistic learning, imposed with punishments and devoid of life. Young Panchak is a misfit in this environment and doesn’t mind facing the unknown risks of his wrongdoings.Subhadra: You have no fear?

All boys: You aren’t scared?

Panchak: No. I always say, let me see what happens.

All boys (closing in): Dada, have you seen a lot?

Panchak: Of course, I have. Last month, on the Saturday when Goddess Mahamayuri’s worship was held, I put some soil from a rat’s hole on a bell metal plate, then topped that with five shealkanta leaves and three lentil grains and blew on it eighteen times.

All: Oh no! Eighteen times!

Subhadra: Panchak dada, what happened to you?

Panchak: The snake that was supposed to definitely bite me after three days has still not found me.

First boy: But you have committed a grave sin.

Second boy: Goddess Mahamayuri must be very angry.

Panchak: I did all this only to see what her anger looks like.

Subhadra: But, Panchak dada, what if the snake had bitten you?

Panchak: Then I won’t have any doubt on this matter.

First boy: But Panchak dada, the window on the north side...

Panchak: I’ve decided I must open that one too.

Subhadra: You will open it too?

Panchak: Yes, brother Subhadra, that way you will have one more member in your camp.

...

Second boy: That’s dangerous.

Panchak: What fun is it if it isn’t dangerous?

Third boy: That’s a terrible sin.

First boy: Mahapanchak dada has told us, that is tantamount to killing one’s mother; because the north side belongs to Goddess Ekjata.

Panchak: I am very curious to find out the fun of committing the sin of killing my mother without actually murdering her.

Assimilation, as opposed to individualism, is at the core of Tagore’s interpretation of freedom. For him, liberty isn’t about the more conventional notion of choosing one’s own way in life. Rather, true freedom, Tagore insists, comes with the conjoining of souls. “The most individualistic of human beings who owe no responsibility are the savages who fail to attain their fullness of manifestation…Only those may attain freedom…who have the power to cultivate mutual understanding and co-operation. The history of the growth of freedom is the history of the perfection of human relationship[3].”

In his play Muktadhara (The Waterfall), Tagore robustly employs this element of freedom. The play relates the story of an exploited people and their eventual release from it. By setting up a dam, Ranajit, the king of Uttarkut, attempts to penalize the citizens of neighbouring Shiv-tarai, who have failed to pay their taxes. Abhijit, the crown prince, differs with this harsh stance and steps forward to help the people of Shiv-tarai by opening a passage that links that state to the wider world. His vision is a broad one—a reflection of Tagore’s own—encompassing the good of all people, regardless of nationalistic boundaries.

Messenger: The crown prince has sent me, Royal Engineer, Vibhuti. Vibhuti: What is his command?

Messenger: For a long time, you have been attempting to reign in our Muktadhara waterfall by building a dam. It broke so many times, took the lives of so many people, and several others were washed away in the floods. Now, at last...

Vibhuti: Their deaths have not gone in vain. My dam is complete.

Messenger: The people of Shiv-tarai still don’t know about this. They wouldn’t believe that the water that God gave them...

Vibhuti: God gave them only water, he has given me the strength to restrain that water.

...

Messenger: Don’t you fear curses?

Vibhuti: What curse! Listen, when there was a labour shortage in Uttarkut, by the King’s decree, we brought over boys who were older than eighteen years from every household in Chandapattan. A lot of them never went back. My machine has come out victorious against many of their mother’s curses. What does the one who fights with divine powers care about human curses?

As it courses through his consciousness, freedom, for Tagore, becomes a vital reference point in his political discourse. He openly censured the increasing materialistic and mechanical nature of the human condition, often paralyzing a person’s mind to the extent that it cannot free itself from narrow compartments, conventional or self-imposed. He observes, “The freedom of unrestrained egoism in the individual is licence and not true freedom… For his truth is in that which is universal in him. The idea of freedom which prevails in modern civilization is superficial and materialistic[4].”

Nandini: Can you hear that song in the distance? A classic example of such a confined mind is Raja or King in Raktakarabi (Red Oleanders) written shortly after Muktadhara. Packed with symbolism and metaphors, Raktakarabi unveils the veiled life of a king incarcerated in his own web—of accumulating wealth at all costs. In contrast is Nandini, a young girl, unfettered and fearless, whose only possessions are her surging life-force and Ranjan—the love of her life. Raktakarabi proceeds to its end with the dramatic act of Ranjan (never seen during the course of the play) getting killed by the king, without the latter having recognized his victim. Filled with remorse, the king ultimately comes out of his shell, and joins Nandini as she becomes the leader of the masses.

A classic example of such a confined mind is Raja or King in Raktakarabi (Red Oleanders) written shortly after Muktadhara. Packed with symbolism and metaphors, Raktakarabi unveils the veiled life of a king incarcerated in his own web—of accumulating wealth at all costs. In contrast is Nandini, a young girl, unfettered and fearless, whose only possessions are her surging life-force and Ranjan—the love of her life. Raktakarabi proceeds to its end with the dramatic act of Ranjan (never seen during the course of the play) getting killed by the king, without the latter having recognized his victim. Filled with remorse, the king ultimately comes out of his shell, and joins Nandini as she becomes the leader of the masses.Background: What song?

…

Nandini: You too come out, dear King, let me take you to the fields.

...

Background: To the fields? What use will I be there?

Nandini: Field work is much easier than your Yakshapuri work.

Background: What is easy is difficult for me. Can a lake dance like a waterfall that wears foam anklets? Go, go, no more talk, I don’t have time.

Nandini: Your power is strange. The day you allowed me to enter your treasury, your wealth of gold didn’t surprise me, but I was awed by the tremendous force with which you so easily piled it up into a mountain. I still ask you, does a glob of gold respond to that strange rhythm of your hand in the way a paddy field would do? Tell me, dear King, aren’t you scared of constantly meddling with the world’s dead wealth?

Background: What fear?

Nandini: The earth pours out her riches of her own volition. But when you rip her chest apart to dig out dead bones as treasure, you bring along the curse of a one-eyed demon. Don’t you see how everyone here is angry, suspicious or frightened?

Background: Curse?

Nandini: Yes, the curse of grabbing, killing, snatching.

Background: I don’t know about curses. I know that we bring might. Aren’t you happy with my power, Nandin?

Nandini: I feel very happy. That’s why I am asking you to come out in the light, to step on the earth, so the earth feels happy.

All these different strands of the theme of freedom are often concurrent, sometimes even converging into each other in Tagore’s analysis and in his works. In the present times, the situations Tagore highlighted in the plays discussed here are manifest in different variations. Entire tribal populations across India are being uprooted with impudence so dams can replace their homes; children’s imagination, especially in urban areas is fuelled more by video games, television, and the internet and less by direct human interaction; education for a lot of societies means little more than students cramming recycled information inside boxed classrooms, pushing for higher grades and bagging lucrative jobs; and capitalist economies all over the world are being remote-controlled by avaricious, profit-minded corporate houses, which care little about the development of those who need it most. In such a scenario, Tagore’s message of freedom, in all its shades, is of utmost relevance.

Bibliography:[1] Foreword to S. Radhakrishnan’s The Philosophy of Upanishads by Rabindranath Tagore

[2] Tagore's quotation taken from "Tagore on the banks of River Plate" by Victoria Ocampo, included in Rabindranath Tagore: A Centenary Volume 1861-1961; Sahitya Akademi; 1961; (p: 42)

[3] The Philosophy of Rabindranath Tagore by Kalyan Sen Gupta, Ashgate Publishing Ltd. 2005 (p:14)

[4] The English Writings of Rabindranath Tagore; Volume Two, Edited by Sisir Kumar Das; Sahitya Akademi

Play Excerpts: Source: Rabindra-Rachanabali (Complete Works of Tagore—Bengali) Translated by Bhaswati Ghosh.

Published in Parabaas, May 9, 2011.

অলংকরণ (Artwork) : Ananya Das - এই লেখাটি পুরোনো ফরম্যাটে দেখুন

- মন্তব্য জমা দিন / Make a comment

- মন্তব্য পড়ুন / Read comments

- কীভাবে লেখা পাঠাবেন তা জানতে এখানে ক্লিক করুন | "পরবাস"-এ প্রকাশিত রচনার দায়িত্ব সংশ্লিষ্ট রচনাকারের/রচনাকারদের। "পরবাস"-এ বেরোনো কোনো লেখার মধ্যে দিয়ে যে মত প্রকাশ করা হয়েছে তা লেখকের/লেখকদের নিজস্ব। তজ্জনিত কোন ক্ষয়ক্ষতির জন্য "পরবাস"-এর প্রকাশক ও সম্পাদকরা দায়ী নন। | Email: parabaas@parabaas.com | Sign up for Parabaas updates | © 1997-2025 Parabaas Inc. All rights reserved. | About Us