-

পরবাস

বাংলা ভাষা, সাহিত্য ও সংস্কৃতি

Parabaas, a Bengali webzine since 1997 ... ISSN 1563-8685 -

ছোটদের পরবাস

Satyajit Ray

Rabindranath Tagore

Buddhadeva Bose

Jibanananda Das

Shakti Chattopadhyay

সাক্ষাৎকার -

English

Written in English

Book Reviews

Memoirs

Essays

Translated into English

Stories

Poems

Essays

Memoirs

Novels

Plays

The Land Where

I Found It All-

Buy in India and USA

-

Audiobook

Looking For An Address

Nabaneeta Dev Sen

Available on Amazon, Spotify, Google Play, Apple Books and other platforms.

-

Cautionary Tales

BookLife Editor's Pick -

পরবাস গল্প সংকলন-

নির্বাচন ও সম্পাদনা:

সিদ্ধার্থ মুখোপাধ্যায়)

-

Parabaas : পরবাস : বাংলা ভাষা, সাহিত্য ও সংস্কৃতি -

পরবাস | Translations | Memoir

Share -

A Scrapbook of Memories and Reflections: by Ketaki Kushari Dyson [Parabaas Translation] : Ketaki Kushari Dyson

A Scrapbook of Memories and Reflections Ketaki Kushari Dyson

Me in 1960 on Magdalen Bridge, Oxford

In 1959, after I had proudly brought out a star-studded issue of the college magazine, Presidency College Patrika, with contributions from many of my contemporaries whose time at Presidency College overlapped with mine and who would, in due course, go on to achieve distinction in different fields, certain things happened to me which had far-reaching consequences in my life.

One day I became aware that something rather strange was happening to the vision of my right eye. It was a holiday, and I was attending a performance of classical Indian music at a music festival. I was finding it difficult to focus on the faces of the performers. I came home for lunch and splashed my face with water. I wondered if the kohl under my eyes had somehow got smeared all over the eyes and was blocking my vision. But no, washing my eyes with generous splashes of water did not solve the problem. I was having difficulty in seeing my plate and the food on it. In the end I had to admit to my parents that I was experiencing something bizarre in my vision. Needless to say, that was the end of their peaceful lunch-time. ‘I suppose I had better ring the doctor,’ said my father.

I had of course been short-sighted since about the age of seven and had grown up wearing glasses on my nose. But so far, I had managed to do most things reasonably well by wearing glasses. One of my father’s favourite ways of checking my eyesight when we came to live in Calcutta was to ask me to read this or that sign when walking in the street. ‘What does it say on that tram-car?’ — he would ask.

‘Drink delicious Ovaltine for health,’ I would reply with confidence.

But things were by no means financially easy for us. As my short-sightedness increased over the years, it was my father who had to pay for the new lenses at each stage. There was no National Health Service for us. Once, as I was playing on the topmost roof-terrace of the apartment block on Rasbihari Avenue, my glasses, newly bought at that time, fell from my nose and one side got a few scratches. They were all glass lenses in those days, not plastic. My father was very upset and cross with me because he didn’t have the money to replace the lenses immediately. I had to carry on wearing the scratched glasses for a little longer. When he was ready to replace them, my myopia had gone up again.

That’s precisely what can happen to short-sighted children. At one stage my myopia doubled and then stabilized. I eventually ended up being under the care of Dr Nihar Munshi, one of the noted eye specialists of Calcutta. He checked my vision at intervals and prescribed lenses for me.

On that fateful day in 1959, my father left the table and phoned Dr Munshi. Dr Munshi seemed disturbed by my symptoms. He said to my father, ‘Ask your daughter to cover her left eye and look in front of her with her right eye.’

I did as I was told and tried to focus on my mother’s face. I was shocked by what I saw. My mother’s face looked like a face cut in two by a railway line. One half was on one side of the track and the other half lay on the other side. The railway line was at the centre of my vision. Appalled by what I saw, I tried to describe it as faithfully as I could, and my father relayed it back to the doctor. Dr Munshi asked my father to bring me to his chamber the same afternoon.

My father drove me there; my mother came along with us to give us support. We were then living in accommodation under the control of the West Bengal government. It was the ground-floor of a two-storeyed building from British days — on Hungerford Street. We were downstairs and some air hostesses lived upstairs.

After his examination, Dr Munshi told me that I had to go home and lie down with my head tilted in a certain way. The first thing I would have to do in the morning would be to get admitted to the Eye Infirmary in the Medical College Hospital, not far from my college. But what about the music festival I was attending, and for which I had tickets? Could I not attend the vocal recital of Sunanda Pattanayak before going to the hospital? Dr Munshi made it crystal-clear that attending any such event was out of the question for me now. He gave my father a chit which would get me admitted to the hospital immediately. It was an emergency. I would need an operation, and the name of what had happened to me was ‘retinal detachment’.

We all knew about the retina, of course, but till that day none of us had heard of a condition known as ‘retinal detachment’. I had seen diagrams of the eye in books, perhaps even in my Elementary Physiology by Bhatia and Suri, and in other books on Psychology which I had had to scan for my Pass course in Philosophy. But the diagram of a healthy eye in a book does not necessarily convey much to a non-specialist. We don’t know what to expect when something goes wrong. Somebody like me usually doesn’t. I have always had difficulty in interpreting diagrams, in moving from two dimensions on the page to three-dimensional reality.

‘Can it not be treated with medication?’ — asked my father. ‘Is there no road to recovery except through an operation?’

‘None, I’m afraid,’ said the doctor firmly. ‘We have to be thankful that nowadays there is at least a viable form of intervention. In the past there was none. People just went blind. And now drive home as slowly and carefully as you can, Mr Kushari, without jerky movements. I shall recommend that the operation be performed by Captain Kiran Sen, the best man in town to do the job. I’ll give you a letter to ensure that.’

I took it all in. While my father was talking to the doctor, my mind was racing, pondering my options and possible strategies. Is this what had happened to blind poets like Homer and Milton? One could be blind and still compose poetry. But I might want to write in other genres as well. I would have to learn Braille. Was some kind of Braille available for Bengali as well? If not, one would have to dictate lines to another person. In short, there was no question of giving up. The question was how I was going to adjust to the new situation.

There were so many obstacles on the way, both major and minor. They had to be cleared. On arrival at the Eye Infirmary I was initially admitted to a general ward as a ‘bed case’, someone who had to lie in bed all the time and was not allowed to get up at all. In those days lying in bed ‘to settle the eye’ was a major requirement prior to retinal detachment surgery. It had to be done, however long it might take. In this bedridden condition, when I was not allowed to move, I promptly caught dysentery, a most unfortunate predicament. In that period my father was allowed basic medical expenses for family members who were financially dependent on him. Anything on top of that would have to be covered by him personally. He was advised to have me moved to a room where I could be on my own. As soon as such a room became available, I was moved there. Meanwhile I was being pumped with antibiotics to get rid of the dysentery. No eye surgery could be done until my eye had ‘settled’ and my gut had been cleared of the dysentery bug.

This took some days, but eventually it happened. I was regularly monitored by the hospital staff, both doctors and nurses, who were exceptionally kind. I was introduced to Captain Kiran Sen, who checked me regularly in his rounds. The patient information sheet at the foot of my bed said: ‘Bed case/ Professor’. Captain Sen was the Professor of Ophthalmology and I was in his charge, which was a blessing for me.

The only intervention available in those days for this condition was ‘diathermic coagulation’. ‘I am going to singe your eye,’ said Captain Sen colourfully, ‘but once it heals you will be OK.’ There was no ‘cryo’ or laser available yet.

As a young man who had just graduated, Captain Sen had served as an army doctor during the tail-end of the First World War. Most cases of retinal detachment he had seen then were among soldiers who had received head wounds. Many soldiers used to get bullets in their heads, which led to eye injuries. Clearly, the case of a nineteen-year-old girl who had not received any such injury was different: perhaps it was something more structural. Some eyes could be more at risk than other eyes, and in the case of a teenager a ‘spurt of growth’ could destabilize the eye and trigger the condition. Apparently that’s what had happened to me. And years later that’s what also happened to my younger son. I was nineteen when this happened to me; he was eighteen when it happened to him. I suppose, being a tall boy, he experienced a ‘spurt of growth syndrome’ a little earlier than I did as a girl.

The hospital where I was treated, the Medical College Hospital, was very close to both Presidency College and the post-graduate departments of Calcutta University, within a few minutes’ walk. Those of us who had graduated from Presidency College had the privilege of a double affiliation — both to that college and to the post-graduate classes of Calcutta University. I could receive visits from fellow students in the visiting hours without any problem. I also received a visit from Professor Subodhchandra Sengupta, the Head of the English Department at Presidency. I was deeply grateful for that visit. When I expressed my gratitude, he reminded me in a firm voice that it was his ‘duty’ to come and see me. There was a remarkably touching mixture of sternness and affection in the teachers of those days. They took their responsibilities as guardians of the students very seriously.

When I was a patient in the hospital, a state scholarship from the West Bengal government was announced in the papers, which would enable a student to go and study abroad. I was encouraged to apply, even by Professor Subodhchandra Sengupta, who wrote a wonderful testimonial for me. Of course, others had to draft and type the application on my behalf. I just managed to put my signature on it from my hospital bed. A few years later I had the good luck to have Professor Sengupta as the Head of the Department of English at Jadavpur University when I worked in that Department briefly — for about a year in 1963-64.

It is worth noting that Prof. Sengupta did not regard my encounter with retinal detachment as a serious bar against an academic or intellectual career. OK, so I had had a brush with an illness which might have led to blindness in at least one eye. But the worst did not happen; I had gone through a successful operation, was cured, studied at Oxford, and was able to pursue a career which needed intensive and extensive use of the eyes. What was remarkable about that generation of teachers was that they expected us to overcome serious obstacles and achieve something in spite of such struggles. There was no suggestion that a deity had punished me for my sins or that this misfortune had befallen me because of my transgressions in this or a previous life. If I had been lucky enough to win a challenge thrown at me by my fate, I had to do something with that victory, achieve something in this or that field. In short, I had to show my mettle. It was a remarkably modern, forward-looking attitude. In 1964 I had once met Prof. Sengupta in the street and he had said to Robert about me: ‘Get her to do research; she is trying to run away from it.’ My ability to do research was verified in his eyes by an article I wrote for him. It was called ‘A Note on Shakespeare’s Language’ and was written for the 400th anniversary of Shakespeare’s birth. Prof. Sengupta thought highly of it and included it in a book published by Jadavpur University for the Shakespeare quatercentenary. I sent a copy of the book to my Oxford College, St Hilda’s, and in the 1970s, when I was formally doing my doctorate, found to my pleasant surprise that my old tutors at St Hilda’s thought very highly of it too. I found that they had made several photocopies of the article and placed them in the college library, urging students to read it. Several students said to me: ‘Oh, so you are the author of the article on Shakespeare’s language!’ That was certainly a gratifying experience. If only my Shakespeare-loving paternal grandfather could have witnessed it!

In 1997, when Robert and I went to see Professor Sengupta after many years, I gained a further insight into the wider perspective of his generation. He was bed-ridden, but he remembered us. I assured him that in my life I had not run away from doing research. He on his part reassured me that he was aware of it. He told us how much he appreciated the fact that while pursuing my vocation as a writer I had continued my life as a wife and a mother. Being able to combine a so-called career with family life was the real height of achievement in his eyes.

Let me return to my narrative. With the surgeon who operated on my eye — on both eyes in the end — I developed a very special relationship. He was like a father to me. He was determined that I would get better, claim my scholarship and go to Oxford for further studies. After the hospital let me go home, I used to visit him in his chamber at home for check-ups, and he was invariably supportive and reassuring.

I only wish that he had taken greater care of himself. As I have indicated before, how bad smoking is for health was not very clear to people in those days, not even to medics. Many men smoked. Nor did people realize how bad smoking was for people around the smokers, those whom we now call ‘passive smokers’. Smoking was frowned upon only by those who had a kind of spiritual objection to it, perceiving it as a nesha or addiction. Addiction to alcohol or cannabis was regarded as not wholesome, but neither public nor expert opinion as yet put tobacco in quite the same category. Indeed, smoking was viewed as a ‘manly’ thing to do. The Coffee House near our college was permanently hazy with cigarette fumes. When Captain Sen checked my eyes with his ophthalmoscope, I could hear his heavy, wheezy, asthmatic breathing. He said he suffered from a condition known as ‘emphysema’. He seemed to know that it had some connection to his smoking, but he clearly had not been able to kick the habit.

Surgery for retinal detachment was done under local anaesthesia. The patient would be conscious, able to hear all the ambient conversation, and also of course to see something with the very eye that was being operated upon. It was a most curious and special experience. I felt like a person who had been shipwrecked and was lying on the ocean-floor. The doctors milling round me were like divers looking at me. The first phase of local anaesthesia must not have been strong enough, because I could feel something, and winced and grunted. Captain Sen told off his assistants and more of the local anaesthesia had to be applied. After some time it was OK and the operation went ahead without any further hassle.

Captain Sen once told me of his frustration with female students who would not show enthusiasm for ophthalmology. ‘They are all fixated on one thing, gynaecology,’ he told me. ‘They think they would be equipped to help other women more effectively that way. But things are not as simple as that. Eye surgery needs fine and precise work. I think girls would be good at it. On the other hand, assisting women in labour and childbirth can be strenuous and heavy-duty work, and men may well manage it better.’

Captain Sen would say such things ostensibly for my hearing, but of course such statements would also be his ‘thinking aloud’ or speaking to himself.

At the end of 1959, when it was clear that the surgery on my right eye had been a success, I began to detect a slight cloud in a corner of the vision of my left eye. My father rushed me to Captain Sen’s home clinic, where he confirmed that a small detachment had indeed occurred in the left eye. I had been so brave before, but this time I broke down and wept like a child. Well, I was just nineteen and a half. The thought especially of lying down again for days ‘to settle the eye’ was most upsetting and unnerving. I asked him why this bilateral detachment had to happen to me.

Captain Sen asked me if I believed in the notion of the sins of a previous birth. ‘Do you believe in that sort of stuff?’ — he asked me.

‘No, I don’t!’ — I said with some vehemence.

‘Nor do I,’ he assured me, ‘but that’s just the kind of thing people used to say in the past and might say about your predicament now.’

Having established that neither of us believed that illnesses were caused by the sins of one’s previous existence, Captain Sen got down to business. He assured me that this was a marginal damage which he could easily repair and once that was done, it would not affect my vision at all.

Captain Sen was determined that I would overcome this latest hurdle and go to Oxford in the autumn of 1960. I was re-admitted to the hospital in January 1960. This time, because the damage was minimal, it did not take long to get the eye ‘settled’. During the operation Captain Sen talked a lot to his ophthalmology students, encouraging them to come close and watch the procedure carefully. ‘Learn, learn now,’ he exhorted his students. ‘I won’t be here for ever, and then you people will have to manage such cases yourselves. So watch me and learn now!’ He waxed eloquent and spoke with great self-confidence. As before, the operation was done without general anaesthesia. Only local anaesthesia was applied.

‘See this girl on the operation table — she is one of our best students. She has won a scholarship to go to Oxford this autumn. But how can she do that with a detached retina? We must fix it for her, mustn’t we? Her going abroad depends on our skills. What do you think, guys, can we do it?’

With another Bengali, Ranjana, on the Canton coming to England in 1960

After I left for England, Captain Sen remained in touch with my father — over the telephone, I presume. Of course, there was no e-mail in those days. In 1961 he came to Oxford for a conference and established contact with me, treating me to a grand meal at the Randolph Hotel. The Randolph of course was beyond the means of students. We sometimes peered through the windows, but never stepped inside. I was curious about its cuisine. How different would it be from the institutional cooking which I had experienced until then? Indeed it was significantly different. I especially noticed how the green beans had been chopped into fine and slender slices and gently fried in butter. It was French haute cuisine.

After the grand dinner Captain Sen said to me that he would like to see my ‘digs’, that is to say, my lodgings. At the time I used to live opposite the Roman Catholic church on Iffley Road. Captain Sen insisted on walking instead of getting a bus and walked slowly all the way with me. It must have been a walk of one and a half to two miles. He was in a very relaxed and chatty mood, and clearly delighted to see that I had settled down to my life as a student at Oxford, thanks, of course, to his surgical skills which had snatched me back in time from the shore of sightlessness. He told me emphatically not to try to do my degree at Oxford in two years. As I already had a degree from another university, I was technically allowed to cover the Oxford course in two years, but Captain Sen wanted me not to strain my eyes. My scholarship was for three years, so what was the rush? I should take my time and spend three full years pursuing the course. I was truly grateful for his advice.

Another advice of his which I heeded was to avoid contact lenses and stick to spectacles. He told me that there were often complications with such lenses and the trouble was just not worth it. I agreed. To me the most important thing was that I had got my sight back through Captain Sen’s skills. I had no wish to fiddle with my eyes for the sake of how I looked. In any case I had grown up with spectacles on my nose.

That day when he came to my lodging on Iffley Road, opposite the Roman Catholic church, Captain Sen was in a happy, chatty, very relaxed mood. I remember that at some point in my interaction with him he did tell me briefly about his experiences in the First World War, and it might well have been that day. As a young man who had just graduated, he had served on the Salonika front. That’s how he had become ‘Captain Sen’ and that’s where he had seen soldier after soldier with head wounds which had led to detached retinas. When he eventually became a full-time ophthalmologist, retinal detachment surgery became his speciality. The paradox of life is that out of the suffering of one set of people, succour can come to another set. From the suffering of those soldiers a new therapy emerged which would help many others whose problems were not directly related to war wounds.

Two eminent ophthalmologists who looked at my eyes in the sixties, one in Ireland, whose surname was Condon, and the other in Canada, whose surname was Cambon, were profoundly impressed when they looked at my eyes. Their verdict was: ‘The surgeon who did these operations on your eyes in Calcutta was one of the very best. There can be no doubt about that.’ They were particularly impressed when they looked inside the right eye, where the damage had been more serious and where therefore the surgery required had also been more extensive.

Sitting in my room that day, Captain Sen asked me what I did just as a hobby. He meant a simple activity — nothing very specialized or serious, something I did just to amuse myself. Indeed I had acquired one, precisely after my detachments, when I couldn’t do a lot of reading. I had had lessons in how to play tunes on the Hawaiian guitar, which was extremely popular in Calcutta in those days. I had found a teacher named Mr Pradhan, a Bengali Muslim who worked for the embassy of Pakistan as it then was. His wife was called Juthi-Bibi. As far as I remember, they lived in the Dharmatala area, which was actually their home territory, and by clinging to which they had managed to survive. Mr Pradhan was an expert in the instrument and well-known for his spirited renderings of waltzes and other catchy dance tunes. We loved to hear him play the ‘Blue Danube’. A Hawaiian guitar was bought for me and arrangements were made to ferry me by car to Dharmatala and back. I even learned the basics of Western-style notation, though I found it much easier to play by the ear. When I came to Oxford, I left that guitar with my sister Karabi and at Oxford, following the advice given to me by Mr Pradhan, bought myself an electrical model of the instrument. I bought it at the High Street shop Russell Acott. On this I played tunes of songs.

So when Captain Sen asked me about my hobby, I happily got out my guitar and played the tune of a Tagore song on it. The eminent ophthalmologist was as thrilled as a teenager. It made my day. My guitar teacher and his wife eventually emigrated to London, where I met them many years later.

To my great regret, I did not get to see Captain Sen after my return to Calcutta from Oxford. This or that event intervened. My sister Karabi got married. The West Bengal government did not offer me a job immediately after my return, so I found myself one in the English Department of Jadavpur University. My Presidency College teacher Professor Subodhchandra Sengupta was the Head of English there at that time and he snapped me up. Formally it was the Rector, Dr Triguna Sen, who appointed me after I went to see him. I had to cope with my first job and prepare lectures and organize tutorials. The question of whether the government of West Bengal would ever offer me a teaching job loomed over me. If they did, I would have to work for them for five years. As it turned out, they made no job offer for a long time, though I had broken records by being the first Indian woman to obtain a First Class degree in English Literature at Oxford University. By the time the government of West Bengal made me a job offer, any obligation I had had to work for them had been rendered irrelevant. They should have made a job offer within three months of my return to India, but very strangely, they didn’t. Which meant that I was free of any obligation to work for them. It was this totally unforeseen circumstance that made it possible for me to get married to Robert in August 1964. Obligation or no obligation, I have of course served Bengal all my life by writing and publishing extensively in Bengali.

When my father got ready to invite Captain Sen to my wedding, we heard that he had passed away just four months prior to that time. So to my keen disappointment I never had the opportunity to introduce Robert to him. I know how happy he would have been to know that I was getting married. And he would have been delighted to meet Robert. I vowed to myself that if I ever published books, I would dedicate my first book to Captain Sen, which I did. My very first book, Bolkol, which was my first collection of poems, was dedicated to his memory.

In this connection there is one memory pertaining to 1963 which I must not omit from this narrative. It concerns my return voyage to India in the autumn of that year. My Oxford friends, the Canadian Jon Wisenthal, the Australian Andrew Deacon, the half-Tamil and half-British Leslie Holden, and Robert, of course, came to the Tilbury docks to see me off. The bulk of my baggage had gone ahead to meet the ship, as was customary in those days. Jon Wisenthal drove us to Tilbury. We squeezed ourselves into his Mini Minor and Robert managed to squeeze himself between a back window and me. He had pieces of fruit, apple or pear, which he was eating, and every so often gave me a piece to eat.

The story of how I became a member of this group of friends may not be amiss here. In the Christmas of 1961 I went to the Lake District for a holiday, under the auspices of the British Council, who used to run such holidays for the benefit of students from the Commonwealth. It was there that I met the Canadian Jon Wisenthal. After returning to Oxford from that holiday in the Lake District, some time in early 1962, I went to say ‘hallo’ to Jon in his college, which was Balliol College. A rather conservative fellow student at my own college later told me that I shouldn’t really have done that. A girl should never visit a bloke unless she has been formally invited by the man to do so. Fortunately, I was blissfully unaware of such rules of etiquette. Jon introduced me to his half-Indian friend Leslie Holden, who was also at Balliol. Leslie’s parents worked in Sierra Leone; they had bought a house in North Oxford where they hoped to live after retirement. Until that happened, the house was being looked after by Leslie. It was in that house that I met Robert a little later, in the summer of 1962. I also met the Australian Andrew Deacon through this group of friends: he was at New College.

Something rather funny happened at the British Council holiday for Commonwealth students over Christmas 1961. The foreign students were asked to present some entertainment in the shape of a ‘song and dance together’, representing their country of origin. There was a Sikh student desperate to show off India’s riches in this respect and he roped me in. He wanted to sing a song and needed a girl to dance to it. He would not take ‘no’ for an answer; I simply had to dance to his singing. I had to do it for India’s sake. I improvised the steps and gestures as best as I could, on the basis of Indian folk dancing and of course Rabindra-nritya, the style of dancing as in Tagore’s dance-dramas. The song was a man speaking to a woman, asking her not to cling to a man who was a foreigner and had to depart. It was pointless trying to bind him with her anchal. The Sikh guy sang it with much feeling; the message of the song clearly meant a great deal to him. Again, it is astonishing how much I remember of the words and the melody of that Hindi song. Perhaps it was a film song of that period.

Ruminating on the past as I am doing in these pages, I wonder if there was, in the students of our times, a sense that we were living in a special historical period. This, after all, was the sixties. Amongst my exact contemporaries at St Hilda’s was Catherine Reeves, the daughter of the famous Bishop Ambrose Reeves of Johannesburg. We often talked about the menace of racial politics and the futility of apartheid.

I had come from India on the P & O boat ss Canton. The Canton was a smallish boat. But I went back on P & O’s ss Himalaya, a very grand ship indeed. It was an extremely comfortable journey. The food was excellent. You could not fault it. The younger passengers were frequently doing rock-n-roll or cha-cha-cha on the deck. Cha-cha-cha dancing had become very trendy at the time, and at the insistence of a young Indian fellow passenger, I had to join in. I had no other option as I was perceived to be a member of the younger generation. The guy explained the steps to me!

On the last night of the voyage I got up very early and went to the deck facing the east. It was dark, and one or two other passengers were there. We all wanted to view the coast of India as it approached.

Slowly, slowly, piercing through the blackness, a few spots of light appeared, and then got brighter and brighter: a chain of lights against the total blackness of the sea and the sky. It was a unique experience, and I did a namaskar to the view, to the coast-line of Bombay. I was back in India, my country of origin. It was an emotional moment. I reflected that I could not have experienced such a unique moment if Captain Sen had not intervened between me and the darkness that surrounds us all. It was thanks to his intervention that I could see the garland of lights which told me that I was approaching India’s coast.

At the time of my journey to the Tilbury docks to catch the boat back to India, it was not clear to my other Oxford friends that Robert and I would eventually get married. Indeed, it was not quite clear to Robert and myself. Things were developing, but we were not quite there yet. In those days in British society a man had to formally ‘propose’ to the woman he wanted to marry, and he hadn’t done that yet. But when a year later Robert flew to India for six weeks, the canny Leslie Holden suspected that something was afoot. By that time Jon had got married to Christine whom he had met in Britain and had returned to Canada. Shortly after Robert’s return to England from his quick Indian trip, Leslie and Andrew came to visit him in Brighton, where Robert was based, pursuing his doctoral research at Sussex University. Many postgraduates at Sussex lived in Brighton, the city closest to the official campus. Leslie had a shrewd suspicion as to why Robert might have gone to Calcutta for six weeks. He came to Brighton with Andrew to find out what was going on. He was carrying a book entitled Love, War and Fancy, by Victorian explorer Richard Burton, to give to Robert in case his suspicions proved to be correct. I believe the book is still lurking somewhere in our house.

The repair job that Captain Sen did on my right eye in 1959, using the only technique that was then available, lasted for half a century without any problem. I lived a full life, raised a family, travelled as and when necessary, and wrote extensively in those years. In 1997 I even had a cataract operation on that eye at Oxford’s Eye Hospital.

After fifty years of diligent service, the repaired eye came undone in the summer of 2010 when I was at an international gathering of Bengalis abroad at Nashville, Tennessee. I was meant to be the chief guest or guest of honour there, but I could fulfil only a part of my scheduled programme. I realized that things were coming undone in my right eye. When I looked out through the window of my hotel room l saw the beautiful building which was there swaying and shimmering like a building in Venice seen from the canal. Maybe there was a pool there which strengthened the Venetian illusion. It was an incredibly surreal visual experience.

Well, that afternoon I was rushed to the local eye hospital, the Vanderbilt Eye Institute, under the charge of an extremely competent delegate to the conference who looked after me as a brother would look after an elder sister. Another delegate to the conference, a young woman, accompanied me and held my hand throughout. The guy under whose overall charge I was definitely needed to have his wits about him, especially when we were leaving that hospital. There was an assistant at the departure point who made a significant fuss over who was going to pay for that particular visit of mine to that hospital. This kind of protocol was completely new to me, with my experience of the British system. If there is a genuine medical emergency, then surely, first of all, one has to find out what exactly has happened. The question of treatment comes afterwards. In this case I did not have any treatment — it was an exploratory visit to ascertain what precisely had happened to me. It seems that in the USA one is expected to pay even for such a visit. This was new to me. The guy who was escorting me left details of the conference where I was a special guest and assured the woman who was making a fuss that the conference would pay for that visit if necessary. I don’t think they had to in the end, but the fuss made by the ‘lady at the gate’, if we may call her that, was extraordinary for me to witness.

The expert who saw me at the Vanderbilt Eye Institute was a doctor of south Indian origin called Rahul K. Reddy. He confirmed that my right retina had become detached again and when made aware that I had no insurance for treatment in the USA, offered to operate on that eye first thing in the morning at no cost. People can be so generous, so wonderful in their humanity, more than we usually give them credit for. It was a great offer, but the problem with current detachment treatment is that one needs approximately six weeks of recuperation after surgery, during which air flight is not allowed because the eye has gas in it that has to be absorbed. Who would look after me for several weeks there? So, after a telephone discussion with Robert, the decision was reached that the best option for me was to go back to Oxford and have the surgery there under the auspices of our National Health Service. Dr Reddy had assured me that though ideally such an operation should be done immediately, it could wait a day or two. Eventually, I was operated on by Prof. Robert MacLaren at Oxford’s Eye Hospital. I returned on a Sunday and had the operation on a Wednesday. On Monday and Tuesday, with one eye shielded, and with Robert’s help, I managed to go through some proofs which had been sent to me. These were the proofs of the second edition of my Tagore translations, sent by Bloodaxe Books.

Some people reading these pages may be wondering how I could be so feckless as to go to a conference in the USA without buying some kind of insurance policy. But the fact is that a conference has some sort of minimal cover in case there is an emergency. Without some such cover, an international conference cannot go ahead. And since such events cause us to be away only for a few days, we tend to rely on that for events in the USA. In the European Union British delegates to a gathering are covered by the protocols of the Union, while in India I can provide for some initial treatment myself from what I earn there from my writings.

Subir Paul, the chief organizer of that conference, whose invitation had brought me there, was himself a medic by profession. He stayed up all night to make the necessary alterations in my travel schedule, and took me to the local airport in the morning. I would have to fly to Chicago first and catch my flight to Heathrow from there. The initial flight was in a draughty and noisy little plane where I was in the care of an air hostess who looked after me as a nurse would look after a patient. She worried that I might feel cold, as the draught in the cabin was pretty strong, and covered me with an extra blanket. I kept my eyes closed and tried to relax as best as I could. When I had to get off at Chicago, the air hostess tried to persuade me to take with me the blanket with which she had covered me. But I did not feel I could do that. What if someone thought I was stealing a blanket from the air line? ‘Nobody will think that,’ she assured me. But I could not bring myself to do that. My experience at Chicago airport fortified my conviction that one had to be very careful in a society dominated by the culture of having to pay for everything. When I was waiting for my next plane, sitting on a bench as close as possible to the people queueing up, the woman in charge told me in a rough tone, without looking up at me, that I must stand in the queue. I then told her that I couldn’t, because I had a medical problem. I was supposed to be in a wheelchair, but the man who had brought me there had dumped me there and gone off somewhere else with the wheelchair. He hadn’t come back. After I made this complaint the woman at last looked up at me and dealt with me directly.

The story of my connection to ophthalmology and ophthalmologists does not, of course, end here. Dr Jyotirmay Bose, an ophthalmologist who had been taught by Captain Kiran Sen, came to see me once when I was in Santiniketan. He left me a copy of his paper done jointly with Ruth Pickford. It was from this paper that I gathered that Rabindranath Tagore had in all likelihood had a problem in viewing the colour red and in distinguishing it from green, the condition known as protanopia. The paper created many reverberations in my mind and in the end led to the major inter-disciplinary research project which I undertook along with Sushobhan Adhikary of Santiniketan, with Robert Dyson and Adrian Hill acting as our scientific advisors. After half a decade of work, the project led to the publication of our award-winning book Ronger Rabindranath (1997). I used to phone Mrs Ruth Pickford at Glasgow from time to time to give her messages from Jyotirmay Bose. Dr Bose had once been involved in surveying the case of the conch-shell workers of Bishnupur in West Bengal, who were complete achromats and didn’t see any colour. To achromats the whole world is black and white and many shades of grey. They have resolutely stuck together as a community, not marrying outside their own caste, perhaps thus perpetuating their achromatic vision.

Let me make an amusing ‘aside’ comment at this point. Do Bengalis have a special love affair with first names which refer to light, illumination, or heavenly bodies that emit or reflect some light? Think of Rabindranath Tagore or his brother Jyotirindranath Tagore. Is it a pan-Indian trait, or more noticeable among us Bengalis? Captain Sen’s first name fits the picture, because ‘kiran’ means ‘light, ray of light’. Likewise ‘jyotirmay’ means ‘radiant’. An ophthalmologist I met recently is called Purnendu, which means ‘full moon’. Purnendu was also the first name of one of our best known cover designers for arty books, including poetry books. Of course, he was an artist and writer in his own right, but it was a special privilege for us to have a book cover designed by him. I was lucky to have the covers of three of my books designed by him.

Once I sat down to ponder our fondness for first names which suggest light in some form or another, dozens of such names began to twinkle in my consciousness. Didn’t my father have a friend who was called Jyotsnanath Mallik, who was the son of the poet Kumudranjan Mallik? Similar names began to tumble down on my lap like autumn leaves. Kiranbala, Kiranabho, Indubala, Deepali, Deepanvita, Deepika, Jyoti Basu, Jyotibhushan, Arunlekha, Arunabho, Pradeep, Pradeepan, Sudeepto, Shashibhushan, Shirshendu, Aalok, Surya Sen, Chandrima, Chandreyi, Chand Sadagar, Purnima, Chandrashekhar, Yaminiranjan, Arun, Aruna, Ardhendu, Deepak, Deepti, Ujjval and Ujjvala, Prabhabati, Bijoli, Prabhat, Angshuman, Rudrangshu … You can add other such names known to you to the list. The phenomenon does suggest a love affair with light and its sources in our language and culture, does it not?

Such is the division of interests between those who pursue the sciences and those who pursue the arts — despite the overlap between those communities in Bengali society through their common pursuit of Tagore’s songs — that it took a few more years before professional ophthalmologists found out about our award-winning book on Tagore’s colour vision. Finally, in November 2011, we made a presentation to the Ophthalmological Society of West Bengal and received a formal recognition of our work on Tagore’s colour vision.

§Sadly, my stay in the ‘digs’ opposite the Roman Catholic church on Iffley Road, Oxford, where I entertained Captain Sen, ended very unhappily. The landlady was going through financially hard times as her husband was out of a job. She rigged up a plan whereby she accused me of stealing some of her cash — something of the order of thirty pounds, as far as I can remember. When I resolutely denied the charge, she threatened to inform my college if I didn’t pay up. I told her to do just that if she wanted to. Then I told the college myself what was going on. The college realized that following due process would be the best and quickest way to deal with the woman who was trying to bully me. My tutors made sure that I would be interviewed by the police in front of one of them. I was interviewed by a policeman and a policewoman in my tutor Miss Elliott’s room, in her presence. She was supposed to be my ‘Moral Tutor’ as well. This business of having a Moral Tutor was also an Oxonian feature. After due investigation, which included looking at my bank account, money going in and out, the police concluded that in no way could I have stolen thirty pounds from my landlady. I was a well qualified foreign scholar with a reputation to maintain, both my own and that of my country. I had a decent scholarship and enough money in my bank account. Why would I suddenly jeopardize my own reputation and that of my country by stealing a relatively small sum like thirty pounds? Of course, thirty pounds was a bigger sum of money in those days than it would amount to now. Nevertheless, it was not credible that a young woman from India would compromise the reputation of her country of origin by stealing that amount of cash. In my mind I thanked the Oxford police for their commonsensical approach and the West Bengal government for granting their students decent enough scholarships. The size of the scholarship mattered a great deal to the police in their final conclusion.

The college authorities informed me that there was a spare room inside the college and I could move there for the rest of that academic year if I wanted to. Which is precisely what I did.

I had of course to tell my parents what had happened. My father asked me to forgive the landlady within my own mind. Poverty can make people behave like that, he said. It can tempt the not so well educated to get through a financial crisis by deceiving someone else and getting some money through that deception. He said he had come across such behaviour as a magistrate in rural Bengal. I was grateful for his realistic, level-headed approach, which helped me to be at peace with myself. I am not making any comments here on those who are super-rich and still defraud others!

After a short spell at St Hilda’s College’s own premises I finally moved, for the rest of my time at Oxford, to the House of St Gregory and St Macrina at 1 Canterbury Road, Oxford, where I stayed until my return to India in the autumn of 1963. It was while I was staying at St Gregory’s House that I witnessed the ferocious winter of 1962-63, which was a spectacular event. Everything froze. The toilets were unusable. We had to go across the road to the public toilets in Parktown. No one who has witnessed that winter can ever forget it.

Group photo in St Gregory’s House, Oxford

At St Gregory’s House we were in the care of Dr Nicolas Zernov (Oxford University Spalding Lecturer in Eastern Orthodox Culture) and his wife Militsa, a distinguished ‘White Russian’ couple settled in Oxford. Dr Zernov belonged to Oxford’s academic community, and he and his wife had been to India. They knew a great deal about Eastern Christianity. I have written about this house and some of the people I met there in my book Nari, Nogori. A few years back, when that little book was given a new lease of life as a part of the collection Ei Prithibir Tin Kahini, published by Chhatim Books, I tried to find out what had happened to Tamara Revenko, the Frenchwoman of Russian-Armenian origin who is at the centre of that narrative, but sadly could not trace her — not from my present perch. It would have required going to Meudon and Paris and undertaking some systematic research, beyond my current capabilities. And to speak the truth, I have written about such a diverse range of people in my books that there would be little point in my chasing, across space and time, the originals behind the portraits presented. They have to remain as I have portrayed them. Countries and cultures, maps and political landscapes have sometimes changed dramatically. In my books people are portrayed as I found them when I interacted with them. I am proud to have portrayed an Algerian woman and a Northern-Irish woman in my first novel. Indeed there are important characters from both Northern Ireland and Southern Ireland in my work, largely modelled on people I have met in life; and I hope Bengali readers will remember them for some time. I am especially grateful to Caroline and Eric, to Djamila and John, and to Daniel who belongs to both Ireland and Thailand.

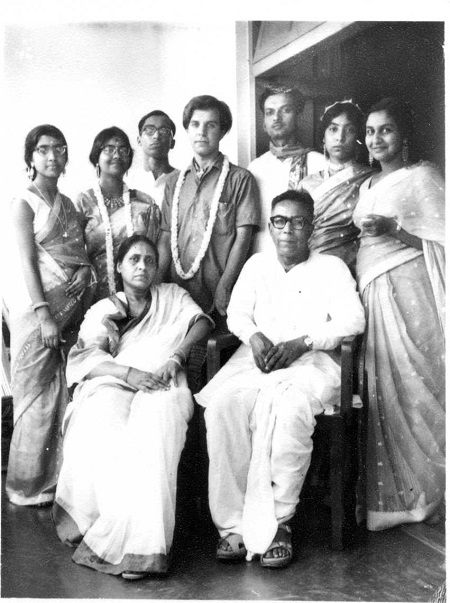

Marriage 1964, Calcutta Front: my mother and father Back: Sister Koyeli, me, brother Amit, Robert, brother-in-law Baren Sen, sister Karabi, cousin Urbashi Dasgupta

In my Brighton days I did hear from my friend from Belgrade who is briefly referred to in the Nari, Nogori narrative and to whom I dedicated my poem about the winter of 1962-63. I dare not now write her name as it was officially spelt, though I knew it once. It was pronounced roughly like ‘Yelitsa Miyatovich’. She sent me a beautiful piece of Serbian lace as a wedding present, which is still in my drawer. It breaks my heart to look at it, because I do not know what happened to her in later years. I tried to contact her a few times, but had no success. Until Nicolas Zernov died in 1980, I used to hear from time to time that Yelitsa was alive and well. But after that, no other link remained. Yelitsa was such a good friend to me at 1 Canterbury Road, and for me she was a personal link with Eastern Europe. She always insisted that she and I belonged to the category she called ‘Eastern people’. ‘We Eastern people’ — she always said with considerable pride. I also remember her telling me with some pride: ‘We are communists in this kitchen.’ She meant that we could use any saucepan or frying pan that was available there, provided we took care of it, and washed and put it away after use. There was an Englishwoman in that house, however, whom we could never train to wash any pans after she used them. She systematically left her dirty pans in the kitchen sink for others to wash.

Yelitsa and me in St Gregory’s House

Yelitsa's Serbian lace

My stay at St Gregory’s House sealed my special connection with ‘Eastern’ people. Already in my first year at St Hilda’s College I had met Sara Joseph, a Malayali who studied PPE (Philosophy, Politics and Economics) and belonged to the community of Syrian Orthodox Christians. Thanks to knowing her, ‘Syria’ and ‘Syrian’ meant so much to me. The knowledge that a fellow Indian’s religion had a connection with that distant land thrilled me. It incarnated the magical processes of history and geography for me. Was that a hopelessly romantic attitude? Maybe. But it was true for me. At the chapel of St Gregory’s House, services were conducted every Sunday morning in Old Russian. I occasionally attended, to the great delight of the Zernovs. There was once a service in Malayalam, conducted by a Malayali priest all the way from Kerala. I attended it, to be in touch with my friend Sara’s background. She was back in India by that time. She eventually had a distinguished teaching career, based mostly in Delhi. Now when I hear about what is going on in Syria, I remember that Sara’s Christianity came originally from Syria, and the carnage there hurts me so much.

At Oxford in the early sixties I knew Badruddin Umar, at that time an ‘East Pakistani’, and I introduced Sara to him. Umar-da’s family’s roots were in Burdwan in West Bengal and he became a prominent intellectual in Bangladesh.

My special connection to ‘Eastern people’ received a further boost when we returned to Oxford from Canada so that I could do my doctorate here. In a few months we bought the house where we have lived since then, where we still live. One day I was startled to hear the distinct call ‘Baba’ in a child’s voice. Our new next-door neighbours on one side were from Greece. The man was Greek and his wife half-Greek and half-Armenian. The children addressed their father as ‘Baba’ just as we Bengalis do. And they prepared stuffed vegetables, as we do, calling them ‘dolmas’. Greeks also prepare and eat live yoghurt. The historical interactions which make such developments possible have never ceased to fascinate me. The Greeks have a quarrel with the Turks about some of these food-related issues. For instance, about the process of making live yoghurt. Both sides claim to have developed it. Many human groups may well have experimented with the process in suitable climatic conditions. Did my ancestors in India learn the art of making live yoghurt (dadhi, dahi, doi) in another geographical region and then bring it over to India through the mountain passes in the North-West? As for the dolma, there may well have been, for us, a live Turkish link in the chain. Anyway, Dennis Balodimos and Emmy Balodimou became our good friends. In addition to dolmas, they also made meat balls very similar to our koftas, and I learned to make their special green bean and tomato stew, called fasoulaiki, which we still make.

From left: Emmy, me, Virgil, Dennis, Haroula, Maria, Igor. Robert took this photo on a subsequent visit they made in 1979.

Inevitably, there is an international slant both in my personal friendships and in my artistic interests. In my writings I have been able to depict or write about a wide range of humanity from diverse backgrounds. My artistic interests have always been international. I take pride in the fact that in the sixties I was the first person to write about Jorge Luis Borges in Bengali. Many contemporary thinkers and writers are discussed in my writings, either in Bengali or in English. Some I have known personally; others I knew only through their books. Eminent fellow Bengalis I have known are of course there, personalities like Sagarmoy Ghosh, Annadashankar Ray, Sibnarayan Ray, Amlan Datta, Ashok Rudra, Satyendranath Roy, Nemaisadhan Bose, Shanu Lahiri, or Indranath Choudhuri. It is a privilege indeed to be able to claim both Sibnarayan Ray and Ashok Rudra as friends! They may have disagreed with each other on many issues, but I can truthfully claim both of them as my friends!

A British Jew like Devra Wiseman has been a steady friend to me since 1960, the very beginning of our student days at Oxford. And I have depicted European Jews, both Ashkenazy and Sephardic, in my Bengali writings. It goes without saying that since my student days at St Hilda’s College, Oxford, I have had British friends from many backgrounds, as for instance, anthropologist Judith Okely, now retired from Hull University, whom I first met in 1961-1962.

St Hilda's alumni get together in 2010, Devra next to me in beige

I have written about British and American writers such as Sylvia Plath, Ted Hughes, Thom Gunn, Vance Packard, Anne Stevenson, Tom Rawling, and Kim Taplin. I have so much enjoyed and appreciated writing for the English ‘little magazines’ Tears in the Fence, edited by David Caddy, and Fire, edited by Jeremy Hilton. I used to enjoy very much the residential poetry workshops organized by David Caddy first in Blandford Forum in Dorset and subsequently in Dulwich College in outer London. I have certainly learnt a great deal about the workmanship needed to write poetry effectively from the poetry workshops I have attended over the years. I do think that the poetry workshop is a very worthwhile tool for honing skills in the art of writing poetry and for the sheer pleasure of enjoying the company of fellow poets. We can meet at each other’s homes for that purpose; we need not hire a hall.

If I open the Contents page of a book of mine like Bhabonar Bhaskarya (= The Sculpture of Thought), published in 1988, in which there are essays, reviews, and interviews, I see that I have written about a host of issues and eminent men and women. The book begins with an account of seeing the performance of Badal Sarkar’s Bhoma, which, I gathered later, had delighted the playwright — at the time I wrote it, I did not know him personally. But let me look at the articles which cover, from the point of view of the Bengali readership, international issues and personalities. These include: a detailed portrait of the Anglo-American poet Anne Stevenson, including an interview I took of her; a consideration, based on a scholarly television programme and the book accompanying it, of the question what kind of historical personality was behind the figure of Jesus; a long conversation with Dr Nicolas Zernov about Solzhenitsyn; the family letters of Sylvia Plath; the impact of television on modern Western life; contemporay British women poets; translated poetry; the eminent dancer Dame Margot Fonteyn; the Faroe islands and their very own poet, William Heinesen, who wrote in his native Danish, and whom I read in Anne Born’s English translation; Karen Blixen, the Danish author who wrote from Africa; Marina Tsvetayeva, the great Russian poet and Edith Sodergran, the Finnish poet who wrote in Swedish, speakers of Swedish being an important minority in Finland; further thoughts on women’s liberation; and the minimalist American composer Philip Glass, two of whose operas, on Mahatma Gandhi and the Egyptian emperor Akhnaten, I saw on television (the very first item in Glass’s opera-trilogy is about Einstein and sadly I missed it when it was shown). Of all the articles I have enumerated here, the one that generated the most heat was the article on the historicity of Jesus. Certain readers, all Bengali Christians, could not accept the conclusion reached in the TV programme and accompanying book that I was reviewing, Who was Jesus? The programme and the book were saying that Jesus was a human being, a historical Jewish figure about whom we can gather a certain amount of reliable information, but whose divinity or supernatural acts we cannot prove. Those readers who were faithful Christian believers could not accept this conclusion and were critical that I was endorsing it. But given the structure of my own beliefs, there was nothing else that I could do.

I am truly grateful to Anne Born for her consistent, unfailing support on issues of literary translation, and to Sita Sheer for giving me a valuable insight into the world of Sephardic Jews. And despite our intellectual exchanges, it was also possible to be perfectly at home with them in their kitchens, discussing cherished recipes and making tea. Anne Born’s Danish-style leek and potato soup became a staple in my kitchen, and Sita Sheer introduced me to taramasalata.

There is an interesting parallel between the inability of certain believing Christians to see Jesus as a fellow human being and the similar refusal of some Bengali Tagore-lovers to see Tagore as one of us. To them, he is always a god.

I have always striven to make my arts reporting international. To bring home to Bengali readers the personality of the eminent French intellectual Simone de Beauvoir, I once translated into Bengali a substantial interview she gave to British television. I obtained the whole script of the interview and the necessary permissions to do the job.

The diverse social anthropologists I have met through the Centre for Cross-Cultural Research on Women at Oxford, led by Shirley Ardener, have left their marks on me. I have also interacted with a range of interesting intellectuals who bridge the imagined East-West divide. For instance, someone like Martin Kaempchen, a German who lives in Santiniketan and knows India well, who helped Sushobhan Adhikary and me to find hospitality in Germany when we did our Tagore-related grand art tour of German museums and art galleries. A Hungarian like Imre Bangha, who teaches Hindi at Oxford and knows several other languages including Bengali has been a good friend for a long time. At a conference in Budapest in which he was one of the organizers I met Liviu Bordas, who corresponds with me by e-mail from Romania. At the same conference I finally met the Finnish writer and translator Hannele Pohjanmies, with whom I had corresponded for some time. Also at the same conference I met the Russian Sergei Serebriany, some of whose queries I was able to answer by e-mail. Susanne Klengel had read and admired my English book on Tagore and Ocampo long before I finally met her when she invited me to a conference in Berlin.

I have reviewed a contemporary like Shanta Acharya whose roots lie in Orissa, who lives in London, and who writes poetry in English. The poet Debjani Chatterjee who lives in Sheffield is of Bengali origin and involved in diverse literary activities, in some of which I have gladly participated. I am deeply grateful to the support I have received as an English-language poet from the eminent Indian English poet Keki Daruwalla.

I knew the American Jewish academic Marshall Berman since my student days at Oxford and once translated one of his essays into Bengali. I also knew his one-time wife Meredith Tax and translated one of her essays into Bengali as well. Both were published in the magazine Jijnasa.

I have known eminent Argentines from Eduardo Paz Leston and Rafael Felipe Oterino to Sonia Berjman. I wrote an article for Berjman which was translated into Spanish and incorporated in her book on Victoria Ocampo and her special interest in gardens. Currently I am in frequent contact with Juan Javier Negri, head of Fundación Sur, about the project to publish a Spanish translation of my book on Tagore and Ocampo.

I have been lucky to know a Slovenian scholar like Ana Jelnikar, who has some knowledge of Bengali and through whose initiatives I have twice had direct experience of Slovenia and through whom I also met the writer Iztok Osoynik.

Likewise I have been lucky to have met and interacted with the Finnish writer and translator Hannele Pohjanmies, with whom I maintain regular e-mail correspondence. The Romanian writer and translator Olimpia Iacob I have never met directly, but we have collaborated on projects by means of e-mail correspondence.

My efforts to translate the poetry of Tagore have taught me both the joys of the actual task and the troublesome politics associated with the job because the poet in question has been made into a god. That leads to the frustration of having to rub against the opinions of those who think that their way of doing things is the best or only valid way. But the truth is that whatever the field, none of us can claim that our modus operandi is the only valid one.

In every area of work, few can know or memorize or demonstrate every relevant detail. Gaps will remain, and we have to learn to work through them as best as we can. It was because I translated a substantial number of Buddhadeva Bose’s poems into English that Hannele Pohjanmies was then able to re-translate from some of my versions into Finnish. And the project to get the poetry of Bose translated, initiated by his daughter Damayanti Basu Singh, brought me closer to her: I had known her in childhood, but she became a genuine friend in my adult life.

Sounak Chacraverti used to work for Damayanti Basu Singh in her Vikalp publishing house and has been like a brother to me. Robert has recently been able to re-establish contact with him through the medium of Facebook.

There are so many others I would like to remember, who have helped me with my projects: all my publishers in India and England; all those who have enabled me to diversify the genres in which I write; all those who, like my good friend Ashoke Sen, now deceased, who have read and admired my books and followed my evolution over the years; those who have pushed me towards the writing of plays and enabled me to publish or translate or stage them. They include Sunil Das of Sangbarta, Ashoke Basu of Pratyasha, and their teams, the actors and actresses who poured their energies into incarnating my lines. For the Bengali production of my first play they include Swati Ganguli, Swati Lahiri, Samrat Sengupta, Debkalpa Das, and others. They have all touched me. Thanks to Peter Bush of the British Centre for Literary Translation, my first play could find the funds needed for its production and tour in English in 2000. With the support of Tom Cheesman and Marie Gillespie the play could be performed at the Taliesin Theatre as part of the Writing Diasporas conference of the University of Wales, Swansea. Gail Rosier and her colleagues put so much of themselves into the job of incarnating my first play in English that Ann Heilmann was inspired to make it a part of the course she taught. She taught Night’s Sunlight first at the University of Wales at Swansea and then at the University of Hull. Gail and her team also did a remarkable ‘rehearsed reading’ with Night’s Sunlight at the University of Bath. This brought me into special contact with the microbiologist Alan Rayner and I was a member of his philosophical ‘Inclusionality group’ for many years.

I haven’t forgotten Sankalita Das and her friend Zulfia who made it possible for my second play to be performed in Bangalore in my English translation of the script. Nor have I forgotten William Radice’s unstinted appreciation of my first play. Thanks to Prabhatkumar Das, my third play, not staged yet, could be published in the magazine Bohurupee. I would like to thank all of them. Sumana Das Sur of Rabindrabharati University, who is pursuing a substantial project on writers of the Bengali Diaspora, has put my three plays together into one edition. I am deeply grateful to Sumana and her husband Anirban for the hospitality they have extended to Robert and me during several of our visits to Calcutta.

While in life, I have always striven to bridge big distances, it is not always so easy to persuade publishers to face mailing costs!

I really believe that in the realm of intellectual and artistic culture we achieve little as lone individuals. Behind every achievement that receives recognition, there is a group that has made contributions. I gratefully remember all those who came to the apartment of Jharna Bose on Southern Avenue, Calcutta, in January 2016. They included old friends from my student days like Esha Dey (born Mukhopadhyay), Krishna Koyal, Chandra Chanda, and the girl who introduced me to ‘Vishwashree’ Manatosh Ray so that I could learn yoga techniques from him to fight asthma.

I began writing down these recollections to enable my English family to visualize my early years in better perspective. As I travel towards the end of my journey, and continue to struggle with a weakening eyesight, I am haunted by the anxiety that I may have forgotten to acknowledge friends who have actually meant a great deal to me. Let me at least mention some names as they come back to me. Debashis Pal lives in Jadavpur and has been reading my books carefully for many years. Dr Ranjana Sidhanta Ash had been trying to help our literary activities gain publicity in England for a long time indeed. The writer and scholar Ghulam Murshid and his wife Eliza, whom I met here in England keep going back and forth between this country and Bangladesh. I have Czech and Slovakian friends whose roots lie in the former Czechoslovakia — Zuzana Slobodova and Franta Nepil, and later on, Andrea Lewis. Let me remember specialists in history and social anthropology whom I initially met through the old Centre for Cross-Cultural Research on Women at Oxford (CCCRW), which was later subsumed under the International Centre for Gender Studies (IGS) — Soraya Tremayne, whose roots lie in Persia and whose husband is British; Camillia Fawzi el-Sohl, who is half-Irish and half-Egyptian and is married to a Lebanese; and Alaine Low, who is British.

I am struck by the wide range of people I have met and interacted with. My friendships have definitely been very international. Let me recall a few more of such contacts.

Sigthor Peterssun, now deceased, was from Iceland; his British wife, Colleen, is still going strong. Joachim Utz I first met when I was briefly resident at the University of East Anglia; his wife Ingrid I met later; and they became good friends. Wangui wa Goro came originally from Africa, while Amita Sen and Dwijadas Banerjee, who have been professionally very helpful to me, I of course first met in Santiniketan. Alastair Niven made it possible for me to find out what the famous Cumberland Lodge was all about. Dai Colven and Celia Wilson have been good friends for many years and expanded my understanding of what it means to be British. Our family friendships have of course expanded through our children. Robert Rowles tells us about life in Japan; Nikou Collis has told us about the Bahai community; Jochen Sokoly has extended our understanding of modern Germany; thanks to Peter Jackson, another friend of our sons, I received an invitation to speak at a TOEBI (Teachers of Old English in Britain and Ireland) conference and gave a lecture on my translations of Old English poems into alliterative Bengali; Steve Keene has deepened our perception of what it means to belong to this part of rural Oxfordshire, and Edward Warrington has brought us scents of Malta. I have been touched by many contacts who are not in any academic or literary professions at all, but have a deep humanistic respect for such activities and have tried to respond to me accordingly. Once, returning to my home base from a trip to Calcutta, I sat next to a man who described himself as a Polish seaman. I could not have had a more convivial travelling companion. He was extremely knowledgeable about the contemporary world and its politics, and we talked pretty much non-stop from Calcutta to Dubai, where we had to go our separate ways. He was touched by the fact that I liked Polish wiejska sausage. After returning home he looked at my website and sent me a mail to say that he had done so. How can we forget such interesting characters we meet accidentally in course of our life’s journey? This is what makes life a memorable adventure.

The news items which currently hit our ear-drums sound dismal. After post-colonial and post-feminist transactions, we are apparently moving into the post-fact or post-truth age. Will the distinction between truth and falsehood fade away for good? What will that mean for us as literary writers? Or indeed for our ethics? But climate change is already here, undeniably: what shall we do about that? For some time now we have been members of a local group based in our village called Kidlington versus Climate Change and gained new friends there who are deeply committed to environmental issues.

Here in the house where we live, neighbours on one side are an ex-policeman and his wife who worked in a supermarket and has now retired; the neighbours on the other side are people retired from the army.

I haven’t forgotten Mishtuni Bevins, herself a denizen of two worlds, to whom I dedicated a long poem in Bengali. Other expatriate Bengalis who have been supportive include Karabi Matilal, the widow of the eminent Prof. Bimal Matilal; Amitabha Chakrabarti, the philosophical physicist who e-mails me from France; Anuradha Roma Choudhuri and her late husband Prof. Bishnu Choudhuri, who were once based in Cardiff but chose London as their place of retirement; the people associated with the Tagore Centres of London and Glasgow; academics like Rafi and Kamal whose roots lie in Bangladesh; Tirthankar and Mandakranta Bose, distinguished academics who have made Vancouver their home.

I remember Dr Aroup Chatterjee, the doctor whose book on Mother Teresa I reviewed; also a young woman who used to sign herself as ‘Soumi Princess’. I have been lucky to have received the blessing of an artist like Shanu Lahiri — I was able to use an acrylic painting of hers on one of my book covers.

Presidency College old students’ reunions in London enabled me to interact with Premen Addy, Deepak Ray and Anup Basu. Saurin Chakrabarti had given me the recommendation which enabled me to get to Argentina with funding from the ICCR. The help I received in Argentina from Mr Jagannathan was crucial to me.

Under Indranath Chaudhuri the Nehru Centre became a place buzzing with activity. Many cultural programmes were organized there that meant a lot to me, such as the release of our book on Tagore’s colours. The British Museum too hosted an important event for me with Sona Datta in charge. Dr Nirupam Chakraborti is an engineering academic by profession whom I have never met directly, though he did speak to me on the telephone once, but who sends me poems from the most exotic locations. The friendship of Dr Parul Chakrabarti, a scientist dedicated to the task of keeping alive the memory of the eminent Sir J. C. Bose, has been a special gift to Robert and me in recent years. This year, 2017, she sent us Holi greetings dyed, as she puts it, in the colours of the palash and nagkeshar flowers. In return, I would like to send her my memories of the remarkable train journey Robert and I made in May 1967 when we went to Vancouver, where Robert was starting as a ‘post-doc’ at the University of British Columbia. First we flew to Montreal, where we spent a few days with Jon Wisenthal’s parents. Then we took the train to Vancouver by the ‘northern route’. It was May, officially spring turning into summer. But through the train’s window we could see a decidedly snowy landscape. The journey through the Rockies was simply spectacular. One can never forget such a journey.

I would like to end this section with a photograph to encapsulate, as it were, the present moment for me. A long time back I had seen, through our kitchen window, a reddish fox in our back garden. It was, of course, a momentary sight, and the animal disappeared within seconds of our exchange of glances. I assumed that the animal had been foraging for food in the back gardens of houses and along the railway line that runs not so far from here. I wrote a poem about the incident: what else could I do? It is in my collection Katha Bolte Dao (= Allow me to speak) and now in the first volume of my Kabitasamagra. But now I want to end with a photograph taken by Robert just the other day.

I had to see the nurse at our GP surgery in North Oxford for a few minutes. There is no parking for patients there, who must find somewhere to park in the vicinity. Robert found such a spot, and there, sitting in his car, looking through his car window in the afternoon sun, he saw, in the middle of urban North Oxford, this fellow citizen of ours, whom he was able to photograph with his mobile phone. I want this image to symbolize the questions that are tormenting me. Let us imagine that fox-kind are as intrigued by mankind as I currently am.

A fox intrigued

/>Any progress we might have made in how to deal with quarrels between nations seems to be swamped by the latest surges of violence between individuals and between groups. I cannot believe what a group of young men coming out of a pub in London recently did to a 17-year-old asylum-seeker. I believe there were one or two girls in that drunken gang too. How can any human being do that kind of thing to another human being? How can any human being deliberately drive a lorry through a crowd? Or blow off a civilian aeroplane flying in the sky? Or plant a bomb inside a plane or train or any other form of mass transport?

I will return to more positive thoughts in the next instalment.

- Cover | Part 1 | Part 2 | Part 3 | Part 4 | Part 5 | Part 6 (Last): Manipur Memories

- এই লেখাটি পুরোনো ফরম্যাটে দেখুন

- মন্তব্য জমা দিন / Make a comment

- মন্তব্য পড়ুন / Read comments

- কীভাবে লেখা পাঠাবেন তা জানতে এখানে ক্লিক করুন | "পরবাস"-এ প্রকাশিত রচনার দায়িত্ব সংশ্লিষ্ট রচনাকারের/রচনাকারদের। "পরবাস"-এ বেরোনো কোনো লেখার মধ্যে দিয়ে যে মত প্রকাশ করা হয়েছে তা লেখকের/লেখকদের নিজস্ব। তজ্জনিত কোন ক্ষয়ক্ষতির জন্য "পরবাস"-এর প্রকাশক ও সম্পাদকরা দায়ী নন। | Email: parabaas@parabaas.com | Sign up for Parabaas updates | © 1997-2025 Parabaas Inc. All rights reserved. | About Us