-

পরবাস

বাংলা ভাষা, সাহিত্য ও সংস্কৃতি

Parabaas, a Bengali webzine since 1997 ... ISSN 1563-8685 -

ছোটদের পরবাস

Satyajit Ray

Rabindranath Tagore

Buddhadeva Bose

Jibanananda Das

Shakti Chattopadhyay

সাক্ষাৎকার -

English

Written in English

Book Reviews

Memoirs

Essays

Translated into English

Stories

Poems

Essays

Memoirs

Novels

Plays

The Land Where

I Found It All-

পুত্রবধূর কলমে গৌরী আইয়ুব এবং প্রসঙ্গত

-

বিশ্বের ইতিহাসে হুগলি নদী

-

বেদখল ও অন্যান্য গল্প

-

Audiobook

Looking For An Address

Nabaneeta Dev Sen

Available on Amazon, Spotify, Google Play, Apple Books and other platforms.

-

পরবাস গল্প সংকলন-

নির্বাচন ও সম্পাদনা:

সিদ্ধার্থ মুখোপাধ্যায়)

-

Parabaas : পরবাস : বাংলা ভাষা, সাহিত্য ও সংস্কৃতি -

পরবাস | Translations | Memoir

Share -

A Scrapbook of Memories and Reflections: by Ketaki Kushari Dyson [Parabaas Translation] : Ketaki Kushari Dyson

A Scrapbook of Memories and Reflections Ketaki Kushari Dyson

Posing with a doll

Since I developed glaucoma some years ago, John Salmon of the Oxford Eye Hospital has been looking after me and has performed the operation known as trabeculectomy on both my eyes to slow down the vision loss. I dedicate these rambles and recollections to him with gratitude.

Chasing old memories may be like chasing the tail of an animal with a distinct will of its own. Sometimes one can see the animal and its tail resting peacefully within one’s field of vision. At other times the animal curls up its tail and rolls and moves about in such a fashion that it becomes difficult to guess what tricks it may be up to. I will begin by saying a few words about the genesis of the present writing project. How did I get here?

From time to time Robert, my husband, has urged me to write down a few pages in English touching my early memories, so that he and our children might form a reasonably reliable picture of those days of mine, with details that could bring them to life.

The request is fair enough. Inside most families we do tend to talk, from time to time, about the past. Indeed, we may talk about it quite a bit. But there’s no denying that writing down our recollections instead of just talking about them does give the past a location, a shape, a name, endowing the bygone with a new lease of life. Being a writer myself, I cannot deny the diverse roles that memories do play in our lives. After all, I myself gave the title Memories of Argentina and Other Poems to one of my own books. Life is a continuous journey and our experiences are gelling to form memories all the time, all the time. Much of what is repetitive does not leave its traces. Imagine what a burden it would be on our brains if we had to remember literally everything that happened to us. Mercifully, we don’t have to do that. We have evolved to retain some memories and to discard others.

Additionally, scenes from the past do not come back to us and live within us in an orderly, chronological, sequential fashion. More often than not, they tumble down into us and move about in a helter-skelter fashion, living tangled, complex, unruly lives within our minds. We try to impose some sort of order on them when we narrate them to others. I sometimes hear them flying past me like clamorous migratory birds. When the clamour dies down, I may say to myself: ‘Well, that’s it. They’re gone now. They’ve left me. I won’t hear them again.’ But that’s not what seems to happen. They tend to come back. Names from some areas of the past may fade a little, but the personalities behind those names, the substance of our interactions with those people: these things do not seem to wither so easily. Indeed, they may persist against all the odds, pursue us with a dogged determination, acquiring independent lives of their own. I dare say that very tragic memories may hound some unfortunate people, both individuals and groups, for the rest of their lives.

My life has been lived both in and in between continents. My personal and literary lives have necessarily meshed and developed patterns of their own. Shall I call those patterns ‘inter-continental’, or ‘trans-continental’, or perhaps, following the language of certain academics, ‘axial’, that is to say, travelling along a certain axis?

Whatever terminology we may employ, it is true that my literary life has been dominated by certain special patterns. Editors and publishers based in Calcutta have kept me incredibly busy. The exigencies of my life have put so much pressure on me that I have never really had a breathing space in which to sit down and write something specifically for my English family. I have received streams of requests from Bengali editors to write about my experiences wherever I might be, not necessarily in a direct manner, but maybe via the other genres in which I might be writing. Also of course I have written articles or conference papers for specialized inter-disciplinary audiences, such as for Translation Studies, or Diaspora Studies, or Tagore Studies. Snatches of my early memories have inevitably escaped into such discourses and, generally speaking, into whatever I may be writing in either Bengali or English at any given time. It is indeed fascinating to watch, in a process of introspection, how our memories guide and shape us. In that way we gain worthwhile psychological insights into the very process of remembering things.

I should have probably paid more attention to Robert’s suggestion much earlier. I feel that I have now entered the last phase of my journey through life. I am frail; most crucially, my eyesight is compromised. If I don’t attempt to write a few things down now, along the lines suggested by Robert, the job will never get done. The fact remains that my earliest memories are set in India, while those of my English family pertain to England. So at least for those stages of life there is definitely some scope for bridging various gaps for better mutual understanding. Subsequently different criss-crossings are inevitable. So why not make a start? I shall probably find that I am talking about the near past as well as about the distant past, and sometimes thinking aloud about the future, asking in which direction we are going.

Let me say right away that I have decided not to use any diacritical marks for either Indian or European terms, because I cannot access them easily with my greatly reduced vision. It is a reluctant decision, but the only sensible option for me now, given the state of my vision and the very basic keyboard and software now available to me. Catering for people with disabilities and who therefore have special needs does not seem to figure very high on the agendas of those who provide us with goods and services. I have a QWERTY keyboard where the keys are marked in a larger than usual size, but the cursor I have to use as I write these lines is as thin as a strand of hair. Here in England, where I live, we now hear more and more about what a burden we old people have become to society. Currently we are hearing this on the news every day. Why worry about diacritical marks when we have entered the Twitter age? This is a hard medicine to swallow for someone who got used to submitting to her publishers very reliable camera-ready copies or PDF versions of whatever she wrote in either English or Bengali.

But my special request to anybody who cares to read these pages is as follows. Please do not look for too much order here. Because of my impaired vision, I can only write in a very large font and view the screen in very high magnification. This means that I can no longer edit my material and impose order on it as effectively and confidently as I could in the past. For that I offer my sincere apologies. The photographs do not always illustrate directly some event in the text, but fit into the period being remembered. It could be that not just my immediate English family, but also a few others in the wider human family to which we all belong, might take an interest in these recollections and re-constructions. Mind you, listening to world news, I sometimes wonder if some people have actually opted out of the notion of a common human family to which we all belong. But let us not, for now, get bogged down in such a dismal marshland.

A caveat here also to readers who may be allergic to the repeated use of the pronoun ‘I’. In the course of my life I have gathered that some people do indeed have such an allergy. But I cannot figure out how, in the context of the English language, the use of this pronoun can be avoided if I am writing about my own experiences. The structure of the English language simply does not permit it. If instead of saying ‘I think’ I just say ‘think’, it no longer refers to me, but becomes a request or command to someone else.

In linguistic communication, the medium and the message are so intimately, inextricably intertwined that unless one has some detailed understanding of the interlingual territory under discussion, one can become thoroughly entangled in misrepresentations of historical realities. The resulting errors can be subtle as well as hilarious. Nowadays in the Western media we often come across a phrase such as ‘Kolkata, formerly known as Calcutta’. I cannot but smile wryly to myself each time I come across a statement like that. Reporters do not usually betray any awareness that they have entered a complicated territory which lies in between languages, the different scripts in which they are written, and the different models of pronunciation they represent. The ongoing historical processes underlying such systems of nomenclature are complicated. The basic Roman script, without any added diacritical marks, cannot even give us a fair indication of how such names are pronounced in the different Indian languages. When did those who speak English decide to write the name of the city in question as Calcutta? Whose pronunciation were they representing? Were those people native speakers of Bengali? Probably not. Were they perhaps speakers of ‘bazaar Hindustani’, a kind of lingua franca prevailing especially among the Marwari mercantile classes settled in that region, which they used to deal with the foreign merchants trying to do business there? ‘Calcutta’ does bear a resemblance to the way the name might have been pronounced in ‘bazaar Hindustani’.

Do today’s Western journalists writing in English know the difference between dental consonants and cerebral consonants, between aspirated and non-aspirated consonants, between diphthongized and non- diphthongized vowels? Would they know how to pronounce my first name as it would be pronounced in Bengali? Without further delving into linguistic realities, a phrase such as ‘Kolkata, formerly known as Calcutta’, is as hilarious as ‘Napoli, formerly known as Naples’.

As far as I know, there were three villages in that region which went into the making of the city in question, They were called Sutanuti, Gobindapur, and Kolikata. Eventually the entire conglomeration came to be called Kolikata. Kolkata is the colloquial version of that name. So it is likely that this version of the name precedes ‘Calcutta’, not the other way round.

In my English nuclear family of four members, Robert was born in Yorkshire and attended school there; our elder son Virgil was born in Vancouver on the west coast of Canada, but retains no memory of his early life there because we left Canada and returned to England when he was about one year old; Igor was born in Oxford; and I was born in Calcutta in pre-partition India. Robert and I met at Oxford as students. As a child, Virgil thought for a while that the place-name Vancouver simply meant ‘birth-place’. His classic childhood statement on this was: ‘But everybody was born in Vancouver, weren’t they?’ Very touching indeed, and the comment indicates the many loopholes through which we willy-nilly acquire language and gather and share information. Let me cite another childhood statement of my first-born to illustrate the point. The first time he saw a hedgehog making its way across the back garden he didn’t know quite how to describe it. Its motion vaguely reminded him of the erratic progress of a spider. But it wasn’t quite like the movement of a spider either. For a start, this was a much fatter creature. So he ran to me to inform me breathlessly that he had seen ‘a hanky-panky spider on the grass’. A creature whose motion had a vague resemblance to a spider’s, but otherwise the creatures were really very different. Hence a hanky-panky spider. In pursuit of a language to describe our ordinary and extraordinary experiences, we often make choices like that.

§My memories begin in a small rural location called Meherpur. If we were to look at the place, as it was then, with today’s eyes, we would call it nothing but a village, at best a biggish village. In the undivided Bengal of the forties of the last century it was a mohokuma, the smallest unit of administration. Meherpur was one such unit in the then Nadia district of undivided Bengal. During my visit to Bangladesh in 2011-12 I was informed that Meherpur had been re-allocated to the neighbouring district of Kushtia, where it was no longer a mohokuma but was a sadar shahar, a town functioning as a bigger centre of administration. It is possible, indeed very likely, that during the early British days the name was written in English as Meherpore.

W. H. Sleeman, nicknamed ‘Thuggee Sleeman’ because of his crucial role in the suppression and eradication of the practice of thuggee in India, called his major book about India ‘The Rambles and Recollections of an Indian Official’. Following that model, I could call these pages ‘The Rambles and Recollections of a Woman between Continents’. But then some people might find that too presumptuous.

Some time in 1942 my father, Abanimohan Kushari, was posted to Meherpur as the SDO or officer in charge of the subdivision. In the 1930s he had been a brilliant student of Economics at Dacca University — Dacca was the way the name was written in English in those days — but found it impossible to obtain an academic job because of the Depression. He had therefore decided to stop chasing the jobs that did not exist and enter the administrative service.

The earliest memory of my life is that of my father, my mother, and myself, their first-born, reaching the bungalow that was to be our home in Meherpur. We must have travelled by train prior to that, but I have no memory of that journey. My memory dawns on that arrival at the house where we were going to live. We arrived in a horse-drawn carriage — from a railway station, I presume. The rhythm of the carriage was making me feel sleepy. I was dozing. Maybe I hadn’t slept much the previous night on the train.

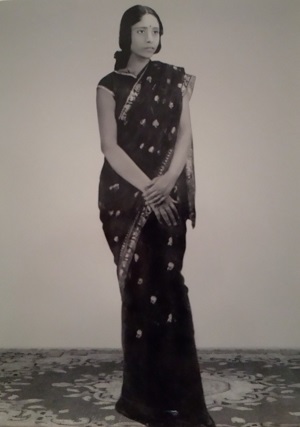

My mother sometime before her marriage

My mother, Amita, nee Dasgupta, had studied in the morning sessions of Ashutosh College in Calcutta for what in those days was called a Pass degree, that is to say, one that was a degree at a general level, but did not involve studying any subject to an Honours level. This was often deemed quite sufficient for a girl’s higher education, after which her guardians could start looking for a suitable groom for her. That was exactly what had happened to my mother.

Although so distant in time, the house in Meherpur is reasonably firmly imprinted on my mind. It was a bungalow with front and back verandas. A bungalow, let me remind those who are reading these pages, literally means a house in the Bengali style. Standing on the front veranda, one could see, at a little distance from the house, what in Bengali we call a shishu tree. The official botanical name of this tree used to be Dalbergia sissoo.

Beyond that shishu tree, in the distance, was my father’s office, housed in some low white buildings. He walked there and back every day. I sometimes made a huge rumpus about my father’s attire when he left for work in the morning. He wore the usual gleaming white cotton trousers, starched and stiff, which were de rigueur in those days. At some point in the winter months he acquired a white cotton jacket to go with it. But winters are so short on the Bengal plains. Soon the need to wear a jacket would be over. My father would try to leave in his shirt sleeves. I would cry and implore him to don his white jacket. Clearly, I thought that he looked so smart in his white jacket that he would be somehow incomplete without it. I would cry and protest vigorously, and had to be restrained.

Many years later, when Robert and I were living in Brighton on England’s south coast, and about to go to Canada, I bought myself an off-white woollen overcoat from the fashionable London store Aquascutum. It was a lovely coat, and I now wonder if my childhood obsession with my father’s white jacket had somehow lived within me and had at last found an outlet.

Standing on the front veranda of the Meherpur bungalow, I knew we had a river quite close to us on the left side, called the Bhairab. Its banks sported thick bushes of flowering kaash, which looks a bit like pampas grass. We sometimes went there for walks in the late afternoons or early evenings.

Looking from the front veranda of the bungalow towards the right, one could see a spectacular jhaau tree. This, I believe, is the casuarina tree. It stood really within the bungalow’s own grounds. Its rustling used to captivate me. This was a very important tree in my early life.

In June 1943 my father bought me a gramophone for my third birthday. It was made by the Company known as Columbia. When it arrived from Calcutta, it was put on a portable cane centre table underneath the casuarina tree and my father played 78 r.p.m. records on it for my musical education. I remember listening on this machine to the ghazals of the husky-voiced Begum Akhtar (or Akhtari Bai as my mother called her), the notes of Love’s Joy and Love’s Sorrow by Fritz Kreisler, as also snatches of Beethoven’s Moonlight Sonata. I could not manage the gadget myself at that age, and was afraid of scratching the surface of the record. I depended on my parents for placing the records and playing them for me.

I think another record that we acquired in this period was of a man and a woman singing in East Bengal dialect. For me it is simply amazing how much I remember of their song-dialogues, which were certainly tuneful, but also, at the same time, dramatic, cheeky, and full of good-humoured banter. This is roughly what happens.

A girl is having a riverside bath. The radiance of her beauty is lighting up the whole ghat, that is to say, the masonry steps leading down from the river-bank to the water’s edge. When I was growing up, this word had become very much a part of the English language as it was used in India. Everybody knew what it meant. Now, I suppose, in the West only specialists know about it, especially in the context of geographical terminology, referring to the Deccan plateau of South India descending in steps to the seashore, as in the Western Ghats and the Eastern Ghats.

To return to the song, as the girl is bathing at the riverside ghat, a man arrives in his boat and tries to strike up a conversation with her. ‘In which country have I now arrived, maiden? You are lighting up the ghat with your radiant beauty — whose daughter might you be? Pray can you tell me that?’

‘And who are you, boatman of the waves,’ she retorts, ‘you who want to know about my home background? Stop this pretext of idle talk and please push off quickly!’

‘Maiden,’ the guy replies, ‘I want to build my home-nest, but I have no companion in my home. I go from country to country, seeking a companion after my heart.’

The girl retorts: ‘Does a companion after one’s heart lie here or there on the road? You are pestering people indiscriminately and for no good reason.’

‘Why, why are you getting so cross, maiden?’ — replies the man. ‘Have I made a terrible mistake in speaking out what is in my mind?’

The girl answers: ‘Keep your thoughts within your own mind and just go back to your home. I have not come across another fellow as cheeky and shameless as you.’

Days pass. The girl says to herself: ‘That day he went away. Since that day I come to the ghat every day. But he does not come back. ... [Singing in the distance] ... Hang on. Isn’t that him singing?’

‘I have come back again, maiden, I have come back! As I was going away, I realized that you had captivated my heart.’

The girl expresses mock anger. ‘The style of your speech infuriates me! As if I had nothing better to do than to chase your heart!’

The man assures her: ‘It is not you who has captured my heart! It is your eyes that have done it! O bird of my heart, why do you seek to find faults with me needlessly? I am unable to move away from this country.’

‘Your hope is huge,’ says the girl, ‘and your words drizzle honey. What can a modest girl like me from a decent, ordinary family offer you?’

‘Smile, maiden, smile,’ the man replies, and join me in my boat with a smile upon your face. We shall sing and sail back to my village.’

The girl exclaims: ‘Then bring, bring, O bring your dinghy close to me, my friend! Let me float on the ocean waves and check out what fate holds in store for me!’

I am amazed to note how clearly I recall both the words and the tune of this song. They seem to sail to me across the years, but of course that is a figure of speech. They are recorded in my brain, and using a recorder, I sang the whole song from start to finish before translating it.

My parents sometime after their marriage

Let me return to the bungalow where my memories begin. Under the casuarina tree was where my parents drank tea in the afternoon when the weather was fine and mild, sitting on cane chairs. Sometimes visitors came to socialize with them there. The tree also looked magical under moonlight and I simply loved gazing at it.

A harmonium was also purchased for me so that I could learn to sing in accompaniment to it. I am pretty sure that this was at my mother’s insistence. It was an expensive German instrument. Like the gramophone, it arrived from Calcutta. My mother was very keen that I should learn to sing. I would sing and she would accompany me on the harmonium.

I recall that some people, most probably my father’s chuprassies (attendants), made amused comments on the fact that we were supposed to be at war with Germany. But my parents always made it clear that the war was between holders of political power. We were not against the German people. Apparently the Germans made the best harmoniums in the market, and as far as my parents were concerned, it had to be the best available instrument for the musical education of their eldest daughter.

When I look back now, I realize that I must have imbibed a certain love of music directly from my mother. For certain reasons, which I shall have to touch on later, I could not become a serious singer or instrumentalist myself, but attraction to music lived deep within me. It probably played a part in the attraction I felt towards Robert when I met him at Oxford. He played on the piano and talked about music. I was also determined that our own children should learn to love music, and I am happy to be able to say that indeed they do. Thanks to the British educational system prevailing when they were growing up, both our sons learned to sing in choirs and our younger son learned to play on the violin, and he has been in one or another amateur orchestra for most years since then.

A little while ago I was talking about cane furniture. In England such items tend to be referred to as wicker furniture because the material is woven. The round cane centre table was a sturdy item of furniture and survived for a very long time indeed in our household. My mother often said that she and my Uncle Shonu, my father’s youngest brother, used to measure my height against it.

Standing on the back veranda of the Meherpur bungalow, we faced our own back garden, where my mother made a diligent effort to grow vegetables, with the help of a gardener, of course. The aubergine plants with their dangling purplish fruit were my special favourites. There were also bushes of gleaming red chillies. At that age I had not graduated to the appreciation of their hot flavour, but I appreciated the contrast between their gleaming red colour and the bright green of the fine leaves. When I refer to the hot flavour of chillies, I mean of course what in Bengali we call jhaal. The heat of temperature and the heat of pungent flavour, two very different qualities, have to be indicated by the same word in English.

Further off, there were large orchards of mango and jackfruit trees. In the height of summer we feasted on the fruit. My mother told me how in a good year villagers would often live on such fruit, without bothering to cook any hot dinner in the evening.

There were many other trees in the back of the house, and the place was alive with the calls of birds: pigeons, crows, doves, kites. An owl — or it may have been a pair of owls — lived in the sissoo tree in the front and made sombre hootings at night. My mother kept some hens in the back, so we had a regular supply of fresh eggs. I remember having coddled eggs for breakfast from a very early age. This dish was associated with a piece of white and pink crockery, which was undoubtedly British. I think we had no ceramics of our own in those days. There were, of course, reddish bowls of baked clay, khuris and cooking pots. Bengal Pottery would be established after Independence. In my early childhood all items of ceramics tended to be British-made. My parents had a beautiful bone china tea set, white with black diamond shapes, clearly given to them as a wedding present. One by one, all the items got broken. Only the covered sugar-bowl survived, and I recall it vividly.

As far as I remember, we ate off kansa or bell-metal thalas and batis, but an exception was made for the breakfast egg. I did have a set of one thala, one bati, and one tumbler, marked for Khukumoni or the Little Miss. As the first-born child of my parents, I also had a silver jhinuk made for me. The word jhinuk imeans a shell. A metal jhinuk is a special deep-bowled spoon with a tipping lip for feeding milk to a baby when the child is weaned to cow’s milk. The silver jhinuk was used to feed my other siblings as well. It stayed in the drawer of my parents’ almari or almira for years and years, until it disappeared. I don’t know what exactly happened to it.

The trees absolutely fascinated me. I loved to see them swaying during storms and shaking their heads angrily in the rain. I used to sit and watch them from the back veranda, which would get lashed by the rain. On moonlit nights they presented another bewitching spectacle, holding the moon in their tangled hair. Sometimes on moonlit nights my mother would sing Tagore songs, including the well-known one on the moon’s laughter’s dam bursting open and the light spilling out. The memory of my mother singing this song was so potent within me that I simply had to include this song when I came to translate Tagore’s poems and songs later in my life.

But what about mosquitoes when sitting on the veranda? I have no clear memory of what was done in this respect precisely in those days, but people were certainly frightened of malaria. Later on in life I gathered that my father had actually sought a transfer from his previous place of posting because malarial fever was raging there. I certainly remember taking quinine at some point in my childhood. I just don’t remember exactly when that was. But I do remember its bitter taste.

When we were in the Meherpur house, my mother was very ill once. I recall a scene in which she was lying down; the illness, whatever it had been, was over; and she was having her hair washed by streams of water poured over her head. The water was going from her hair into a big bucket. For some reason I thought that she was recovering from malaria. But now I wonder if she was simply recovering from chickenpox. We were all very scared of certain diseases in those days, including malaria, smallpox, typhoid, and tuberculosis. I knew about quinine from an early age, and my parents were religious about not drinking unclean water and about vaccinations and inoculations whenever they were available.

Meera who died long before I was born

A first cousin of my mother, Meera, a ‘mamato bon’ of hers, did succumb to tuberculosis at a young age. She was the first child of my mother’s maternal uncle and his wife. I think she died before I was born, but I cherished a photograph of her sitting on a chair. The photo meant a lot to me. It encapsulated for me the process of history. The mother of the dead woman was my mother’s ‘mamima’, the wife of her sole maternal uncle K. C. Sen. There is an opinion sometimes aired in the Western media that women’s lives are not valued or remembered in India. But India is a subcontinent, and while there are some pockets in that vast land mass where this may be true, it is not true of the community within which I was born and raised. My mother’s ‘mamima’ did care deeply about the memory of her dead girl and had a small trunk in which she had saved some of her saris. On fine days she would open the trunk and lay the items out on the top roof terrace of her house to expose them to the sun and breezes, so that they did not get musty. After the sunning and airing she would fold them again and put them back in the trunk. I witnessed the ritual when I was staying in their house on Palit Street, opposite Maddox Square, while studying at Presidency College in the fifties. I was deeply moved and the experience did generate one of my poems in that period, though I carefully veiled the experience and blended it with other strands of reflection, including a reference to my own prematurely dead maternal grandmother and to one of my own contemporaries.

My maternal grandmother who died

when my mother was five years oldAnother of my mother’s first cousins, the daughter of one of her mother’s sisters, caught tuberculosis, but luckily lived to see the days when appropriate medicines were coming into the scene. She survived and I did meet her. I have a clear memory of her. Her family too paid meticulous attention to her health needs and her overall welfare.

When I went to school I found that many girls had had typhoid. I was one of those who had never had it. Nor did any of my siblings. But we had whooping cough and measles when we came to live in Calcutta after Independence. After starting school at the age of eight I developed asthma. But let me not anticipate that time yet.

Very vivid in my mind is the memory of seeing lightnings in Meherpur. I used to be extremely scared of seeing them and would close my eyes. Sometimes the lightning flashes were quiet, just displaying light. Sometimes they were followed by thunder. My mother explained how lightning could sometimes reach us as thunder. As soon as I saw a lightning-flash, I would close my eyes in terror and wait to find out if it would reach us as sound. Sometimes it did, sometimes it didn’t. I used to count the moments anxiously. My mother had explained about the transit of sound taking longer than that of a visual display. Sometimes there was no sound, just the snake-like motion of the light. I was scared of both snakes (which I hadn’t yet seen) and the motion of light in lightnings. Sometimes, after counting the moments with closed eyes, I would at last hear the rumbling of thunder in my ears. The end of the waiting would be an enormous relief. The fear of lightning and thunder lived within me for a very long time indeed. Late evening rain would be listened to from indoors, with a lantern burning in the living-room and frogs croaking loudly outside.

Through the long hot afternoons I would stubbornly refuse my mother’s invitations to come and have a siesta with her indoors. I would sit on the chowki or four-legged wooden platform that was permanently left standing on the back veranda. This was my home in the daytime. It was where I perched. Sitting on it, I learned to read and write. I watched the world from it. During the day I stared dreamily at the dense orchards of fruit trees outside. I never tired of staring at them. I watched the washed saris drying in the sun on the grass, the hens pecking at the ground for food, the crows eating the lunch left-overs given to them and cawing listlessly from time to time. Ants fascinated me too. I watched them journeying along the cracks in the veranda floor with minute particles of food in their tentacles, sometimes passing on their luggage to another ant. They clearly communicated very well with one another. But I had to be careful watching red ants, because I had been told that their sting could be venomous. Red ants did sometimes wander over the washed saris laid out flat on the grass to dry. Of course, I wasn’t wearing saris yet. The frock was my costume in those days. The saris drying on the grass would have been either my mother’s or the maid’s. I suppose they shook them thoroughly to make sure that they were not ferrying any ants indoors, especially the naughty red ants, who could apparently do much mischief.

Then there was that unseen enemy, the tiger. I never saw one, just heard stories about tigers from the maid Shibu — I suppose her name must have been Shibani and that she was called Shibu for short.

Shibu found it extremely convenient to lull me to sleep at night with stories of the tigers that, according to her, roamed along the river-banks at night, passing by the clumps of the kaash that grew there. She would just have to utter the word baagh (‘tiger’) to strike terror in my heart. Especially at night. The tiger apparently came over to the veranda for shelter on rainy nights. He sniffed us through the doors to find out which naughty children were refusing to go to sleep. ‘Be quiet and go to sleep right now,’ Shibu would whisper, ‘the tiger will come to the veranda and find out by sniffing and listening through the closed doors that there is a naughty girl in this room refusing to go to sleep.’ My younger sister would fall asleep pretty fast. Listening to my parents having their dinner in the adjoining room, I would desperately try to fall asleep.

One afternoon when I was dawdling on the veranda, my mother, anxious that I should have a siesta, called out to me to come indoors to do so. ‘Or else the tiger might come and get you,’ she added. Keen to avoid an encounter with the dreaded beast, I hurried towards the bedroom, only to trip on the chowkath or the bottom part of the door-frame. The metal catches for closing the doors from inside would also have been there. I fell and cut my chin. It bled and had to be stitched immediately. The fear of infections was absolutely paramount in those days. My parents were as afraid of infections as I was of encountering a tiger. The slight dent on my chin from the cut and the stitch remained for most of my life. My mother learned her lesson and from then on avoided such drastic tactics to persuade me to come indoors. I dare say that my father must have told her off for using such a strategy!

Looking out from the back veranda, where I spent most of my waking hours, the casuarina tree would have been to my left, and somewhere on the right side lived a security guard and his young wife in their own cottage. I think they must have been Biharis. We called the young woman ‘the sipahi’s wife’. It is from this word sipahi, often softened to sepai, that we got the Anglo-Indian word sepoy, as in the expression ‘the Sepoy Mutiny’. The young woman wore the sari in the ‘up-country’ fashion, as we called it, that is to say, with the anchal or sari-end in the front. She wore dangling nose-rings, but most of her face was usually hidden by her dangling sari-end. She looked so very shy, but she was pretty keen that my mother would try some of her home-made chutneys and pickles. They were actually delicious. She was also a keen gardener herself, and her neat little fenced garden sported aubergines and jhingas.

The rooms in the bungalow were sparsely furnished. My father’s job was transferable, so our life-style had to be simple. In fact, until I came to live in England I did not really understand or appreciate what a European-style bourgeois life really meant. The concept of ‘interior decoration’ did not hit the Calcutta media till the mid-sixties. The enormous importance given to furniture and wall-paper in England puzzled me. Indeed, I did not fully appreciate such details until I visited Yorkshire after my marriage and heard my mother-in-law and her friends talk at length about such things. Since then I have understood that there is a basic difference between hot and cold climates in such matters. There is no way you can possibly survive in a cold climate by lounging on a chowki on the veranda all day. In cold climates the fireplace and the mantelpiece evolved to become the focus of attention within a living-room.

There was indeed a fireplace in the lounge in the Meherepur bungalow. The room was used by my father as a study. We never lit a fire there ourselves, but we were assured by my father’s chuprassies that indeed the sahibs used to do so.

In our Meherpur home there was the beautifully woven cane suite, the round centre table and chairs of which could be taken outside on fine days. And there were a few other essential items of furniture made of beautiful solid wood, which my mother had been given by her family at her wedding. These travelled with us from place to place, as was the custom in those days. The dressing-table mirror was an early victim of this modus vivendi and got broken in one such transit even before our days in Meherpur . In my childhood I only saw its bottom part. Later on, when we were in Calcutta, my mother had to persuade my father that with three daughters growing up, a tall mirror was needed so that the girls could learn to drape their saris in front of it. Yes, I remember learning how to drape a sari at the age of fourteen in front of the newly acquired mirror. I did it as neatly as I could, tucked the sari-end to my waist, and off I went, by public transport, to Lady Brabourne College at Park Circus to begin my Intermediate Arts course.

For me at Meherpur, a curiosity greater than the fireplace was the huge punkha in what was our dining-room. It was not in regular use. We had no punkha-puller in attendance as such. Some attendants just demonstrated how it was worked, more to amuse me and my sister than for any other reason. Thinking about it now, it must have been pretty dusty for lack of regular use! I presume that a punkha was in regular use in my father’s real office, but I never went there. We came to Meherpur in 1942, and I suppose that by that date the administration could no longer afford to give the SDO a punkha-puller both in the office and at home. If the officer was just a native, not a pucca sahib, he would just have to fend for himself!

In those days, in houses not connected to electricity, light was provided mostly by the sturdy hurricane lantern or the humble little lamp called the kupi.

I have some special memories relating to the different rooms of the bungalow at Meherpur. Towards the end of 1942 Uncle Shonu, my father’s youngest brother, came to visit us, and he had to get some extra care for what I was told was a ‘carbuncle’ on his back. Not any old boil, mind you! The English word ‘carbuncle’ was used to underline the gravity of the situation. The beast had to be opened up by repeated hot compresses. My mother did this at regular intervals until it opened up. My uncle got better and left. Pretty soon thereafter one day my mother occupied that very room. And what was quite incomprehensible to me: she got into that room and I was not allowed to go there and talk to her! This was an unprecedented crisis in my little life. I had never experienced anything like this. What! I could not go inside that room and talk to my mother! I was barred access to her? Why? What had happened to her? The doors were not bolted from the inside. The curtains were in situ. A few strangers in white saris were going in and out of the room. But I was not allowed to go in. This was an outrage. What was going on in that room?

I could hear muffled noises. I sensed that they were making a fuss over my mother. I reached a conclusion. That was the very room where Shonu-Kaku had been ill with his ‘carbuncle’. That must be the room, I thought, in which people had to be segregated when they fell ill. That was a sick-room, I told myself. But what was my mother’s illness? Nobody had told me that she was ill in any sense. The only way I could deal with this sudden crisis in my life was to yell with all the might in my little lungs. I was restrained by a maid who held me tightly in her arms — was it Shibu? — but I struggled to break free, without success, of course. I kept yelling, ‘Ma, why are you hiding in Kaku’s room? What’s the matter with you?’ I must have been given assurances that she was not too poorly, but I was inconsolable. Nothing like this had ever happened in my little life before. I was sure that something terrible must have happened to her.

At some point the muffled hubbub inside that room subsided and I was told: ‘Now you can go and talk to her. You have just had a little sister. You can go in and see them both now.’

Fair enough. My mother was lying down and looked more or less OK. The little bundle to which I was introduced looked like a baby too.

Perhaps this is where I should point out that it was like a matter of religious belief to my parents that when a woman gives birth, medical help should be available to her — not just a traditional dai or untrained midwife, but modern medical help. The dais apparently cut the umbilical cord with anything sharp they could lay their hands on, leading to so many women dying of infections at childbirth and so many cases of infant mortality. My parents believed that a woman giving birth should do so in a hospital or maternity home, or where someone with proper medical training could help her. Thus I was born in the Ramakrishna Mission maternity hospital on Lansdowne Road in Calcutta. The Ramakrishna Mission had been exemplary in bringing childbirth within the ambit of modern clinical practice.Karabi, the second child of my parents, was born at home in Meherpur on 7 January 1943. Her date of birth is the beginning of my measurable personal calendar. Because of that date I know that my memories begin when I was roughly over two, approaching that magical age of two and a half, when things begin to happen which you may well remember for the rest of your life. By that date I know that our arrival in the Meherpur bungalow in the horse-drawn carriage had happened indisputably in the second half of 1942. We had arrived and settled in, and some time had passed, and Uncle Shonu had had his famous ‘carbuncle’ and had recovered and gone away. All these things had happened before I was two and a half, that magical age when things begin to happen which you may remember for the rest of your life. I have no memory of my mother letting me feel her belly and telling me that there was a baby sibling for me growing there. She may well have done that, but I have no recollection of such a conversation. In contrast, I remember my mother’s third and fourth pregnancies clearly.

The people going in and out of what I was calling Uncle’s room came, as I realized a little later, from a missionary enclave not too far from where our house was. They ran a clinic and a ‘lady doctor’, as these professionals were called in those days, came from there to help my mother in her ‘birthing’. Yes, the lady had made some visits prior to this event, but of course I did not know the real reason for her visits then. She was not a memsahib, but a native woman doctor. She could have been a native Christian, I suppose. She looked trim and professional in a white sari neatly draped and tucked in. I had imagined that her visits were solely to socialize with my mother and drink tea with her.

When I was able to walk longer distances, I did visit the missionary ashram, as we called it. The ashram had rose bushes as well as bushes of colourful variegated leaves. There women sang in choirs. They were native Christians, in white saris with black borders. They could have been Hindu widows converted to Christianity by missionary activists, to give them new opportunities in life. They sang in Bengali, and I remember snatches of their songs, which I have quoted in my poem on Meherpur. ‘Come, come, let’s go and see the child Jesus./ The Lord Jesus was born in David’s city today.’ David’s city was ‘Dayudpur’ in Bengali.

I never felt any ‘sibling jealousy’ when Karabi or indeed my other siblings arrived. On the contrary, I took my responsibilities as the Biggest Sister of the family very seriously. Karabi soon became a toddler and I helped her to walk up and down the back veranda. I was proud of my responsibility. Taking her out to the vegetable garden at the back was a task I took very seriously. I could not do this on my own and had to enlist the assistance of Shibu the maid. So I would say to Shibu. ‘Bu (shortened from Shibu), let’s go and gather some fried aubergines.’ I called the vegetable itself ‘begun-bhaja’ because that’s how I saw it on my plate, as fried pieces. What was gathered in the garden in the morning was at lunch-time miraculously delivered on the thala as round fried pieces.

The non-availability of modern sanitation in vast stretches of rural India is in the news in the British media from time to time. I suspect the climate and the natural environment have a lot to do with the origin and development of relevant practices. But what might have worked in the past cannot work when the density of population is much, much higher, and when social manners have also changed substantially, sometimes drastically. I have mentioned the unused fireplace and the not-much-used punkha. Let me recall the bathroom.

Looking from the back veranda, it was on the left-most side, at a right angle to the veranda. This was the casuarina side; on the extreme right was the entry to the kitchen. The bathroom had buckets of water and a commode for each person. I had a dainty wooden one made specifically for me. It was comfy. For some reason, when my sister was ready for one, it was a cane one that was made. It then developed prickly bits that stuck out and made the seat uncomfortable. Of course, my sister disliked that. In the mornings, after we had drunk our hot milk, there would be a race between us. Who could reach the wooden potty first? Honestly, the things we remember!

But one of the reasons why I am writing this piece as a string of memories rather than as an ordered historical narrative is to have some understanding of the process of memory itself.

The potties would be emptied and cleaned by a sweeper woman who sometimes hung around, impatiently urging us to hurry up. ‘Push, push, sisters!’ she would urge. ‘Nothing ever gets done without a big push!’ Perhaps many things wrong with us in later life could be traced by a modern psychiatrist to this pretty demanding potty training!

The carpenter who fashioned the wooden potty also engineered a wooden doll’s bed for me. It was an exquisite little four-poster bed in reddish wood. I cannot honestly remember if I had a tiny mosquito net for it.

I have mentioned the big chowki that was my constant daytime haunt. I learned to read and write on it. I should modify that statement immediately by saying that in truth, I don’t remember learning to read Bengali — as far as I can recall, I always knew how to read Bengali, which my mother says I taught myself to do at a very early age.

Writing was done with suitably narrow pieces of chalk — we might call them ‘chalk pencils’ — on a wood-framed slate writing-board. My mother would frequently set me the charming ‘task’ of writing a poem. ‘On what?’ I would ask somewhat impatiently. ‘How about a rainy day?’ — she might ask. If I pouted or indicated that I had already written such a poem, she might pause, as if pondering other options, then say, in a bright, breezy, cheerful tone: ‘Or a spring morning perhaps?’ Saying that, she would disappear into the kitchen, which was at the other end of the veranda. The bathroom was at one end of the long back veranda, and the kitchen at the other end.

I would write my poem and wait impatiently for my mother to re-appear. Once she disappeared inside the kitchen, it would be a long time before she would emerge again, and I was not allowed to go inside the kitchen to look for her. I used to get very impatient. I felt that I could have written ten poems during that time. That, of course, was not possible on a small slate writing-board.

What my mother did with me was what we nowadays call ‘poetry workshop’. If I managed to write a decent poem, she would copy it herself onto a khata or exercise-book, as my handwriting was not very ‘formed’ yet — it was on the wobbly side.

So yes, following this method, first writing with a piece of chalk, then allowing my mother to copy the piece onto a paper exercise-book, I did accumulate a fair number of poems. Rainy days, rainy evenings, requests to the season of spring to come and visit us soon, accounts of little trips on the road by jeep if I was allowed to accompany my father somewhere — I did them all diligently. Occasionally, my mother would copy one of my poems to one of her cousins and send it off in the post. I began to acquire the reputation of a little poet amongst such ‘aunties’. A mother’s female cousins are of course aunties in the Bengali family.

I also knew the English alphabet — strictly speaking, the Roman alphabet — from an early age. It is looking at newspapers that did it, my mother used to say. But decoding the English way of reading and writing was actually harder for me. Unlike Bengali, the script was without vowel-signs and conjuncts, and with capitals and a lower case for every blessed letter, the system turned out to be more difficult for me to master. I could not understand how the syllables were put together and meant to be pronounced. One question I was often asked, when I came to England at the age of 20, was this: seeing that I spoke English so correctly and fluently, surely I must have spoken English at home from an early age? But the truth is that we did not speak English at home. Those who asked the question marvelled at the answer.

Yes, I do remember being baffled by the English syllables — how the script put them together. When you do not hear a language swirling round you, it becomes a different kind of challenge. I had a ragged English primer with which I used to sit down on the chowki and struggle to master syllables. ‘Cat, bat, mat, rat, hat,’ I would recite, vaguely wondering what those objects might be. It was not as much fun as reading Tagore’s Shishu or Katha o Kahini was.

Talking of memories, I wonder how and when I learned about certain things which people in Britain learn at a young age, but which did not concern me. The room with the unused fireplace was my father’s work-room at home. He sometimes dictated official letters to a personal assistant there. But in Meherpur he never told me anything about his precise administrative role in the service of the British Empire. I think that strictly speaking he was in the Bengal Civil Service. Some people at Oxford, when I arrived there as a student in September 1960, did not believe me when I said that I had no clear idea of the design on the British flag. Had India not been a part of the British Empire? Indeed I knew about the existence of the Empire, but we did not pay much attention to its symbols. When I was growing up in India, I never really took in what the British flag looked like. What the Indian flag would look like when we gained independence from British rule preoccupied us much more, but of course that was a little later, nearer to 1947.

In that room with the fireplace my mother once showed me a map of Europe and tried to explain to me that there was this distant continent called Europe, from which the sahibs had come, and that there was a great big war raging there right now. ‘When that war comes to an end,’ she explained, ‘the sahibs will go home and we shall be independent.’ She told me that in that distant region called Europe, there were countries called Poland, France, England, Italy, Germany etc, and that they often fought each other, making a very big mess. I marvelled to hear such tales.

So yes, I knew that a war was on, and at some stage learned that the Japanese were embroiled in it too, that in fact they might drop bombs on us from planes. Whenever a small plane came groaning in the sky above us, we would look at it with trepidation. Might that be a Japanese plane? But no plane ever came to drop a bomb on Meherpur. It was clearly too insignificant a target. I remember a little nursery rhyme I heard in my childhood, though I am not sure at what stage I heard it. Probably not in my Meherpur days. Perhaps a little later.

Sa-re-ga-ma-pa-dha-ni,

Bom phelechhe japani.

Bomer aagaay keutey saap.

British boley, ‘Baap re baap!’Sa-re-ga-ma-pa-dha-ni (seven notes of the scale).

The Japanese have dropped a bomb.

On the tip of the bomb sits a keutey snake.

The British exclaim, ‘Father, O Father!’A clear reference, surely, to Pearl Harbour (December 1941), but I never heard the incident discussed by adults in my early childhood. The keutey is a small, black, extremely venomous snake. I think I used to know its official zoological name once, but can’t remember it now.

I have only very recently woken up to the fact that I had not fully taken in what the expression VE Day really meant, not until the year when the 70th anniversary of the event ‘Victory in Europe’ was splashed on British television. I knew that it had a connection with the word ‘victory’, but did not see the whole phrase as ‘Victory in Europe’. The full implications of Nazism were of course not clear to me at all in my childhood years. I must have missed any mention of the 50th anniversary of the VE Day in the British media, being engrossed in my own projects. I did not always watch TV religiously.

In 1945 no fuss was made over that particular day, VE Day, wherever I might have been. We didn’t even have a radio set in those days. My parents read newspapers. I am sure that as a civil servant in British India or British Bengal, my father must have followed the political news pretty closely, but he did not discuss such events with us children. A few years later, after Independence, when we had come to live in Calcutta, I learned that he had had a German friend when at Dacca University — that was how the name was written in English in those days — and had been extremely worried about this friend’s safety. By then my father had taught himself quite a bit of German. This German friend had been a visiting student at Dacca and had been good at student debates. One day a picture postcard arrived from him to our apartment on Rasbihari Avenue in Calcutta. It had the picture of a reindeer on it, with a snowy landscape behind the animal. The picture made a very deep impression on me and I still remember it. I hadn’t seen snow yet, but by then had read about it. I had been to Darjeeling with my parents and Uncle Shonu when I was very small, but I was too young then; it was before the dawn of my memory.

With my father in Darjeeling

My father’s German friend had been married and divorced by the time the picture postcard arrived in Calcutta. My father must have had some address for him to initiate (or resume) the correspondence. I believe they exchanged a few letters at that stage. Then I gathered that the German friend had married again, and had got divorced a second time. After that the correspondence seemed to cease, and I was left with the impression that the Europeans were very complicated people.

At some point after Independence, when we were living in Calcutta, I did hear about the atom bomb that had been dropped on Hiroshima and Nagasaki, but I don’t think that I grasped the full meaning of the term ‘atom bomb’ at that age. Nor did I come across the term ‘the Holocaust’ in my growing years, just as I did not understand the full horrors of the slaughters in the Punjab at the time of the Independence and Partition of India. I knew that Hitler had killed ‘sixty lakhs’ of Jews, but I don’t think I knew the English expression ‘the Holocaust’ when I was growing up in India. I could not understand at all why the Jews would be regarded as so very different from Christians. To me they were all ‘sahibs’. Jesus Christ was the founder of Christianity, and he was a Jew, was he not? It was not at all clear to me why Jews and Christians would be bitter enemies. It was a profound mystery to me.

Our parents must have tried to shield us kids from violent news of a political nature. I did not hear about ‘The Great Calcutta Killing’ of 1946 until much later. We weren’t in Calcutta when it happened. The fear of communal riots was lurking there, simmering, but our parents spared us the gruesome details. I therefore grew up without comprehending why any group of humans would need to hate another group of humans so very violently that the business would lead to massacres. When I reached a certain age, I knew that such things happened, but did not comprehend why they did.

I certainly never heard of the ‘Quit India’ movement in those days, but in 1943 at Meherpur I was vaguely aware of a food shortage. The women who came to sell rice or eggs to my mother told her that people were leaving the villages in search of food. It was all hush-hush. My mother would ask me to run and play when such tales were reported. I would then get off the veranda and walk on the grass, but keep my ears alert so that I could catch snatches of what they were saying. All around us the countryside consisted of rice fields, separated by the aals or raised earth-ridges. Sometimes when I went out with my father for a walk, I could see people walking briskly over the aals, with some bundles over their heads, going from one village to another in search of food. There seemed to be nothing wrong with the fields. The harvest was not yet ready, that was all. Many years later, as an adult, I learned how the rice had been commandeered for the army, and my father explained what he had had to do, as an officer in charge of a subdivision, to deal with the rice shortage.

The raised earth-ridges which separated the fields were an integral part of the local landscape around Meherpur. In our afternoon walks across the country, my sister and myself were accompanied by our father’s chuprassies and we saw nothing wrong with our neighbouring countryside. It looked lovely and serene in the sun.

I have one interesting memory in this context. It is my first memory of a real dream, and it is from my Meherpur days. I dreamt that one afternoon as we were walking with one attendant, another one came from the bungalow in a great hurry and asked us to return immediately, because a miraculous thing had happened. There were many moons up in the sky, not just one. In my dream we dashed back immediately and found that people had put wooden stools, one upon another, to look at the plethora of moons. The raising of the viewing height was to see the moons better. This curious dream about the multiple moons has stayed within me all my life.

Amongst the few people who came to socialize with my father in Meherpur was one of his colleagues. He was known as the Second Officer and always arrived in a noisy motor-bike. Because of the bhat-bhat-bhat-bhat noise his engine made, we nicknamed him bhat-bhatia.

In those days everything of interest seemed to happen on the veranda. My ears were pierced on the back veranda of the Meherpur bungalow. The local goldsmith came and did it at one go. Or rather two go’s — one ear after the other. What was used to pierce the ear-lobe became your first ‘sleeper’ earring, which did not have to be taken off when sleeping. The use of 22-carat gold wires meant that there would be no infection. When I yelled, they held me and pushed an omelette into my hand to comfort me. I ate it all up to console myself!

The local goldsmith also came to the veranda with the necessary equipment to make a pair of slender gold bangles (churhis) for me. It was fascinating for me to watch the process. He lit a fire and he huffed and puffed. My mother had yielded to the cultural pressure put on her by her female relatives, who held the view that the wrists of girls should not be ‘bare’. Many years later I wrote the long poem in two sections, entitled ‘Churhi’, which told the story of what happened to my very first pair of churhis. It became very popular. I shall come to that story in due course.

From the worldly theme of bangles let me move on to the profound question of the existence of God, a topic to which I was introduced in a summary fashion at Meherpur, on the veranda, of course, where else? On the question of God, my mother said to me, ‘Some people believe that there is a God, but there is no way to prove it.’ I have had no reason to disagree with her position to this day.

Many years later a believing Muslim gave her a copy of the Koran in Bengali translation, hoping to change her mind. But my mother saw no reason to change her mind even after dipping into the book. She continued to be a sceptic. I myself read an English translation of the Koran when I was a ‘grown-up’. I think it was a translation by N. J. Dawood.

The deity under discussion was, of course, the big God that powerful theologians like to talk about. But in real life this was combined with the multitudes of gods and goddesses we had to accommodate when growing up in the specific region and particular community within which I was born and raised. I have no memories of the Puja festival in Meherpur. I dare say we must have always gone over to Calcutta for a few days, to my mother’s relatives in Palit Street, for the Puja holidays. I don’t want to interrupt my memories of Meherpur with recollections of the Puja holidays, which I think in the Meherpur days were always spent in Calcutta.

My earliest memories of books are about a tatty copy of Tagore’s poems for children, Shishu, and a little later a copy of his narrative poems, Katha o Kahini. Then there was the rat-cat-hat-bat-mat primer for learning English I have already referred to. I read Krittibas’s Bengali Ramayan and Kashidas’s Bengali Mahabharat a little later when I was in Malda, and I shall mention them in due course.

Later again, there were other things: an anthology of Vaishnava poetry, another one of more contemporary Bengali poetry called Kavya-Deepali, edited, I think, by Narendra Dev and Radharani Devi, and from 1947 onwards the Tagore anthology Sanchayita. But these are, of course, after my Meherpur days.

In my early childhood foreign literature was represented by a Bengali version of Uncle Tom’s Cabin, given to me by my Aunt Leela, my mother’s brother’s wife, for my fifth birthday; a Bengali Hans Christian Andersen collection; and an English anthology entitled A Child’s Garden (or was it Treasury?) of Verse. I also recollect an illustrated English Robinson Crusoe, which I could not read in the Meherpur days, but which I enjoyed looking at while my mother told me the story.

I am not absolutely sure of this, but I wonder if my Bengali Uncle Tom’s Cabin was where I first read about snow and ice, and the perils of crossing a frozen river when a thaw had begun. Somebody was slipping and sliding over floating ice, and the picture presented in the description made no sense to me. I had never seen snow or ice, so could not really imagine or visualize such a landscape.

Again, I am not quite sure in which book I read this, but in the Meherpur days I came across a suggestion in a book that a man could be described as being in a state of perilous poverty just because he was not wearing a hat and shoes. It made no sense to a child growing up in the tropics. I was surrounded by hatless and shoeless people, and personally I did not possess a hat at all. I wandered all over the veranda with ‘naught on my feet’ and the only problem about walking on the grass in the early morning was the slightly chilly feel of the dew. I do remember taking this query to my father, who explained to me what being hatless and shoeless might mean in a really cold climate.

Questions to do with my immediate environment were much more important in my mind than questions about the existence of a God. I had accepted without any problem my mother’s position that the existence of a God could not be verified. But the mythological approach, the stories about gods and goddesses, could be compelling. For example, stories about the Mother Goddess and her family. These stories were a rich mix of natural and supernatural elements. All my early memories of our annual Puja festival are from the Maddox Square Puja in Calcutta and have nothing to do with Meherpur. I do remember my mother’s female relatives doing the little rituals of saying goodbye to Goddess Durga and asking her to come again next year. I remember my mother being somewhat sceptical about such rituals: she had to be dragged to the park to witness them. We must have gone to Calcutta every year for that festival and stayed with my mother’s relatives in Palit Street. The religious festival that I associate with Meherpur is Saraswati Puja, in honour of the goddess of learning. The Mother Goddess Durga’s two daughters are Saraswati, the goddess of learning and the arts, who holds a veena and rides a swan, and Lakshmi, the goddess of wealth and prosperity, who is accompanied by an owl. My mother maintained that it was somewhat obscene to pray: ‘Give me wealth, give me riches’. It was much better to pray for knowledge. So at Meherpur she would install a clay image of Saraswati in one of the rooms, and I would recite some simple prayers on behalf of my sister and myself before flinging our floral offerings to the goddess. That was simply great fun.

Climbing up to a slide in Maddox Square, Palit Street, Calcutta

Talking of rituals, I remember coming to Palit Street, to the house facing Maddox Square, built by my mother’s maternal grandfather, because this senior relative had just died. We got off a taxi, went straight into the front room, where a group of women were wailing. My mother immediately joined them on the chowki where they were sitting. Karabi and I were hurriedly led away indoors. Small children had to be protected from excessive lamentation and coming face to face with the reality of death. I have no memory of my mother’s maternal grandfather. I just remember that his name was inscribed on a marble plaque at the gate of the house.

But I do remember his wife, my mother’s maternal grandmother. I find it very difficult to talk about relatives in English as the kinship vocabulary available in English is so very limited. Bengali is much richer and more varied and precise in this respect, indicating the greater importance of the network of the extended family in Bengali society. We have many separate kinship terms to indicate the different types of grandparents, uncles and aunts, cousins, grandchildren, and in-laws. We can make distinctions between relatives by blood and relatives by marriage. Seniority also matters, so that we can immediately determine the right mode of address, showing proper respect. It would be impossible to deal with the ramifications of an expanding extended family otherwise. Father’s brother is different from mother’s brother, and father’s elder brothers are also distinguished from his younger brothers, as are their wives. These are all inscribed on the language for the smooth running of the patriarchal society, with concessions to make the hierarchical structure bearable and workable without too much stress or friction. There is a lot of fine balancing. Father’s elder brothers will exact a great deal of discipline from you, whereas Mother’s brothers are expected to indulge you more. In Bengali ‘Mother’s brother’s house’ means a place where a child is indulged. Father’s eldest brother’s wife will inherit her mother-in-law’s mantle as the female head of the household, so has to be treated with due deference. One could write a chapter of a thesis in social anthropology, analyzing the elaborate kinship terms finely inscribed on our language.

But of course all this must be changing again now that families are getting smaller and smaller, and living most of the time in small nuclear units and not connecting with an extended family as much as they used to do in my own childhood.

I have often wondered: did words for ‘brother’ and ‘sister’ go out of vogue in China when they adopted the one-child family? But surely they must have retained the words, otherwise they could have made no sense of their own literature.

India has, of course had her pockets of matrilinear/matriarchal society, and they have struggled to maintain their life-styles, often surrounded by hostile patriarchies. In course of an academic conference, I once had the good fortune to visit the women’s market in Manipur, where women do all the selling and buying, and men are not allowed to set up stalls. It was an unforgettable experience.

From the women’s market at Manipur let me travel conveniently to my memory of my mother’s mother’s mother, whom I remember reasonably clearly. She inhabited a particular room in the Palit Street house. She had many pictures of mythological personalities all round the walls, images on the floor, with lamps and flowers. It was her bedroom, with an attached bathroom, and it was her ‘puja’ room for her private prayers as well. A framed studio photograph of her prematurely dead daughter hung on the wall as well. We saw it as soon as we entered the room. That was my mother’s mother, my Didima, whom I never saw, who died from a post-natal complication not curable in those pre-antibiotic days, leaving behind two very young children, my mother and her younger brother, my sole mama or maternal uncle. The two children were brought up by various units of the extended families as and when necessary. I have written about this photo in my English poem ‘Mothers’. When I came to live in that house for the purpose of studying at Presidency College, this was the room allocated to me, and I used to sleep right under my maternal grandmother’s framed photograph. One could see the photograph as soon as one entered the room. I remember the furniture arrangement in the room quite clearly. One could see my study table and chair on the left. I also had some small shelves for my books. There were two single beds, each with its own dedicated mosquito net, as the mosquito was truly feared. I occupied one bed against one wall, with my little trunk underneath it to hold my clothes. There might well have been an alna or clothes rack as well, perhaps near the bathroom door. It took me some time to realize that this was a plumbed and fully functioning ‘attached bathroom’, with a chair-style toilet, clearly designed for the use of my maternal great-grandmother in her old age, which I could happily use, without having to come on to the balcony and heading for the facilities for everyone’s use. This was a great bonus at night.

The other bed, against another wall, was occupied by the youngest lad in the house, the grandson of my mother’s sole maternal uncle, who was the male head of household. The ceiling fan whirled right in the centre of the ceiling. The currents of air cooled the floor more than anything else! There are weeks when the parasite-bearing mosquito does not breed. At such times some of us ‘young ones’ slept on cotton mattresses on the floor of a very big room, with the ceiling fan cooling us deliciously.

But I am moving too much in the fast forward mode in time. And I knew that this would happen! I am in the 1950s before finishing my account of the 1940s! This is happening because I remember the geography of this house on Palit Street (as it was) so well, and who slept where, and the details are so firmly imprinted on my mind, while the house itself, alas, exists no more. I shall have occasion to speak about this house again, I think. It was architecturally innovative and charming, and my parents were married in that house.

- Cover | Part 1 | Part 2 | Part 3 | Part 4 | Part 5 | Part 6 (Last): Manipur Memories

- এই লেখাটি পুরোনো ফরম্যাটে দেখুন

- মন্তব্য জমা দিন / Make a comment

- মন্তব্য পড়ুন / Read comments

- কীভাবে লেখা পাঠাবেন তা জানতে এখানে ক্লিক করুন | "পরবাস"-এ প্রকাশিত রচনার দায়িত্ব সংশ্লিষ্ট রচনাকারের/রচনাকারদের। "পরবাস"-এ বেরোনো কোনো লেখার মধ্যে দিয়ে যে মত প্রকাশ করা হয়েছে তা লেখকের/লেখকদের নিজস্ব। তজ্জনিত কোন ক্ষয়ক্ষতির জন্য "পরবাস"-এর প্রকাশক ও সম্পাদকরা দায়ী নন। | Email: parabaas@parabaas.com | Sign up for Parabaas updates | © 1997-2025 Parabaas Inc. All rights reserved. | About Us