-

পরবাস

বাংলা ভাষা, সাহিত্য ও সংস্কৃতি

Parabaas, a Bengali webzine since 1997 ... ISSN 1563-8685 -

ছোটদের পরবাস

Satyajit Ray

Rabindranath Tagore

Buddhadeva Bose

Jibanananda Das

Shakti Chattopadhyay

সাক্ষাৎকার -

English

Written in English

Book Reviews

Memoirs

Essays

Translated into English

Stories

Poems

Essays

Memoirs

Novels

Plays

The Land Where

I Found It All-

Buy in India and USA

-

Audiobook

Looking For An Address

Nabaneeta Dev Sen

Available on Amazon, Spotify, Google Play, Apple Books and other platforms.

-

Cautionary Tales

BookLife Editor's Pick -

পরবাস গল্প সংকলন-

নির্বাচন ও সম্পাদনা:

সিদ্ধার্থ মুখোপাধ্যায়)

-

Parabaas : পরবাস : বাংলা ভাষা, সাহিত্য ও সংস্কৃতি -

পরবাস | English | Memoir

Share -

In Memoriam: Mohammad Rafiq (1943 - 2023) : Carolyn B. Brown

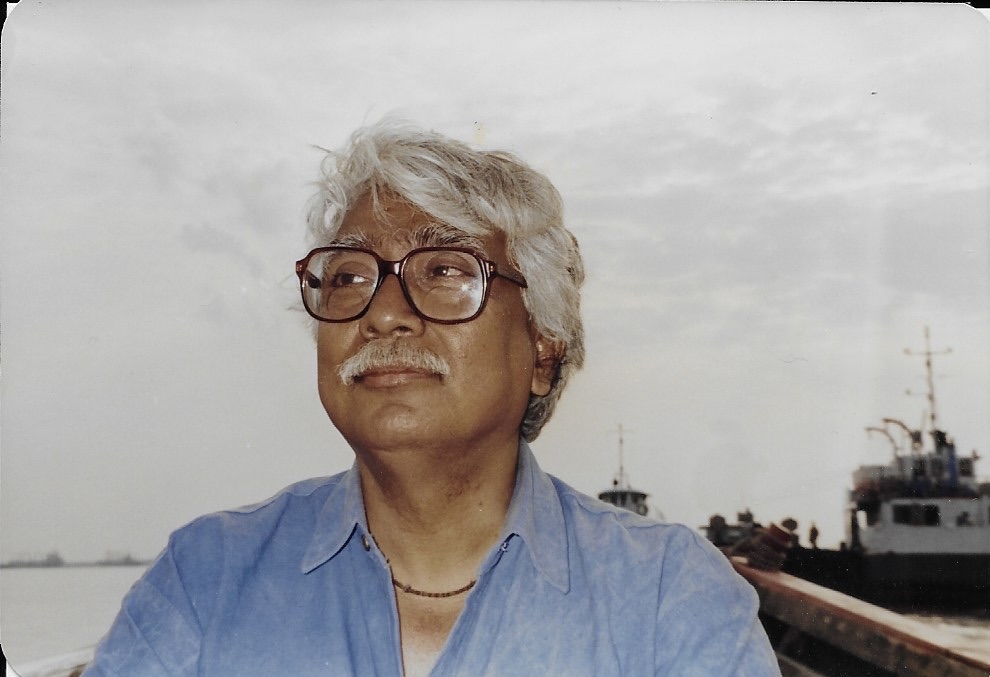

Mohammad Rafiq (Bangladesh, 1997)

Epitaph : Mohammad Rafiq

translated from Bengali to English by Carolyn B. Brown

here lay a grave, crumbled by time, washed

away by the river,

in the end the poet’s skull holds a scoop of water

three fistfuls of dirt—

perhaps a stanza survives or two lines

one caesura!

“Epitaph” (এপিটাফ) is the final poem in

Mohammad Rafiq’s 2008 collection, Nonajhau (নোনাঝাউ)

Mohammad Rafiq was born in Baitpur, in the Bagerhat district of Bangladesh, in 1943. On August 6, 2023, he suffered a heart attack that proved to be fatal during a visit to his home village, where he has now been buried. Rafiq will be remembered not only as an award-winning poet many times over but as one of the heroes of Bangladesh’s 1971 Liberation War, jailed twice as a student for protesting against the Pakistani regime, then serving as a Sector-1 officer, motivating freedom fighters, as well as with the Radio Center of Independent Bengal. His third volume, Kirtinasha (1979), brought him recognition as a major poet. In the early 1980s, his “Open Poem” became a rallying cry for the protest movement that eventually brought down the Ershad regime. He taught in the English Department at Jahangirnagar University for three decades before his retirement in 2009. The following account of the experience of translating Mohammad Rafiq’s poetry from Bengali into English is adapted from the translator’s preface I wrote for This Path: Selected Poems of Mohammad Rafiq (Dhaka: Bengal Lights Books, 2018). From time to time, I listen to a very old phonograph recording, the soundtrack of Jean Renoir’s 1951 cinematic love-song to Bengal, The River. My parents played the record so often when I was growing up that as I listen now, I realize how it pervaded my youth, almost as if it were a promise. Even so, I could never have imagined that one day I would understand the words of the boatman’s song. As I grew older, I came to love the films of Satyajit Ray, engaged not only by the characters, the scenery, Ravi Shankar’s music, and the expressive but elusive spoken words. I was completely dependent on the English subtitles, just as I was dependent on Tagore’s own prose renderings when I first read Gitanjali, with no hint the original poems were, in fact, songs. I begin with these recollections because they have a direct bearing on my approach to translating poetry in general and Mohammad Rafiq’s in particular.

From time to time, I listen to a very old phonograph recording, the soundtrack of Jean Renoir’s 1951 cinematic love-song to Bengal, The River. My parents played the record so often when I was growing up that as I listen now, I realize how it pervaded my youth, almost as if it were a promise. Even so, I could never have imagined that one day I would understand the words of the boatman’s song. As I grew older, I came to love the films of Satyajit Ray, engaged not only by the characters, the scenery, Ravi Shankar’s music, and the expressive but elusive spoken words. I was completely dependent on the English subtitles, just as I was dependent on Tagore’s own prose renderings when I first read Gitanjali, with no hint the original poems were, in fact, songs. I begin with these recollections because they have a direct bearing on my approach to translating poetry in general and Mohammad Rafiq’s in particular.When we first met to work on translations of some of his poems in the fall of 1993, Rafiq was a participant in the International Writing Program at the University of Iowa and my job was to bring the poems, stories, plays, and essays by writers from around the world into English. Rafiq’s instinct was perfect. Although we had a rough handwritten translation in front of us as a starting place, he chose to first recite the poem in Bengali. I didn’t understand a word, but my ear told me immediately that I was listening to genuine poetry. This moment is the origin of my conviction that I must, from first to last, translate “by ear.” The literal version might provide a rough understanding of the words along with a structural framework, but unless I could fashion an English that captured the emotional current of the original as conveyed by the sound of the words, the patterns and changes in texture, the poem would remain untranslatable. My initial efforts were grounded in face-to-face discussions with the poet, replaced later by written conversations and most important, recordings of the Bengali originals, which I listened to over and over, as if memorizing a piece of music, before putting pen to paper.

This was a daunting task. I was determined to learn Bengali, despite having almost no access to learning materials at the time. Simply finding a comprehensive dictionary took months; acquiring university-level instructional tapes, more than a year. When the squiggles of Bengali script turned into letters and words, I felt as if I’d deciphered the Rosetta stone! My leisure reading became focused on the history and culture of the region. The further I went, the more I wanted to acquaint myself not just with the language and facts but with the land itself and the people who lived there. I wanted to taste the fish that darted through the lines—a mouthful of rui mach, a bite of ilish. I wanted to see the trees whose names branched out before me—bakul, batabi, jarul. When I learned the words echoing sounds that water makes, I wanted to be afloat on a river—the Meghna, the Padma, the Jamuna.

I wanted to walk the paths through a village and beyond. In time, I had the good fortune, through a series of grants and the hospitality of the poet and his family, to visit Bangladesh and immerse myself in sights and sounds and flavors, to listen to personal accounts of historical events, to meet writers and artists—and to find out what adda is all about.

A path in Baitpur, the poet's birthplaceMy translations of Rafiq’s poetry, now gathered in This Path, are informed by those experiences and by my conviction that a translator should try to offer the reader an experience as close as possible to that of a native speaker reading the original. It’s a common misconception that a translator must be fluent in the spoken “target” language. I can say amar bangla khub kharap (my Bengali is very bad) with an accent convincing enough to provoke a flood of Bengali much too rapid for me to comprehend. The facility to utter the words of another language in a steady stream, however, is less important than the ability to imagine in one’s own language not only the effect of the original words of a poem but to render them in a way that a native speaker might even recognize the melody. I will remain forever grateful to Mohammad Rafiq for drawing me into the world of translation, for introducing me to Bangladesh, and for many years of collaboration and friendship.

See also:

1. Mohammad Rafiq's brief biographical sketch

2. Translations of more poems by Mohammad Rafiq in Parabaas

Photographs by Carolyn B. Brown

Tags: Mohammad Rafiq; Bangladeshi Poet; Parabaas Translations - মন্তব্য জমা দিন / Make a comment

- মন্তব্য পড়ুন / Read comments

- কীভাবে লেখা পাঠাবেন তা জানতে এখানে ক্লিক করুন | "পরবাস"-এ প্রকাশিত রচনার দায়িত্ব সংশ্লিষ্ট রচনাকারের/রচনাকারদের। "পরবাস"-এ বেরোনো কোনো লেখার মধ্যে দিয়ে যে মত প্রকাশ করা হয়েছে তা লেখকের/লেখকদের নিজস্ব। তজ্জনিত কোন ক্ষয়ক্ষতির জন্য "পরবাস"-এর প্রকাশক ও সম্পাদকরা দায়ী নন। | Email: parabaas@parabaas.com | Sign up for Parabaas updates | © 1997-2025 Parabaas Inc. All rights reserved. | About Us