-

পরবাস

বাংলা ভাষা, সাহিত্য ও সংস্কৃতি

Parabaas, a Bengali webzine since 1997 ... ISSN 1563-8685 -

ছোটদের পরবাস

Satyajit Ray

Rabindranath Tagore

Buddhadeva Bose

Jibanananda Das

Shakti Chattopadhyay

সাক্ষাৎকার -

English

Written in English

Book Reviews

Memoirs

Essays

Translated into English

Stories

Poems

Essays

Memoirs

Novels

Plays

The Land Where

I Found It All-

পুত্রবধূর চোখে গৌরী আইয়ুব এবং প্রসঙ্গত

-

বিশ্বের ইতিহাসে হুগলি নদী

-

বেদখল ও অন্যান্য গল্প

-

Audiobook

Looking For An Address

Nabaneeta Dev Sen

Available on Amazon, Spotify, Google Play, Apple Books and other platforms.

-

পরবাস গল্প সংকলন-

নির্বাচন ও সম্পাদনা:

সিদ্ধার্থ মুখোপাধ্যায়)

-

Parabaas : পরবাস : বাংলা ভাষা, সাহিত্য ও সংস্কৃতি -

পরবাস | Buddhadeva Bose | Memoir

Share -

Reliving through Letters: A bit of time again with Buddhadeva Bose : Clinton B. Seely

In academics, the doctoral student is sometimes warned that a Ph.D. dissertation is not a book. By that is meant the following: Details, digressions, even extensive documentation, which may be pertinent to the topic and may demonstrate to one's professors the depth of one's research, might be seen by editors at a press as tiresome, not absolutely necessary, and even unjustifiably expensive with respect to the cost of production of the published book. Some academic presses even refer potential authors to guidelines on how one should convert a Ph.D. dissertation into a publishable book. That process may entail adding material; often it involves removal of parts and concision throughout. For instance, the preface to the published book, A Poet Apart: A Critical Biography of the Bengali Poet Jibanananda Das reads at one point:

Buddhadeva Bose, 1953 Jyotirmoy Datta--himself a poet, former fellow at the Writers' Workshop in Iowa, and for a time visiting lecturer at the University of Chicago--introduced me to Jibanananda's wondrous world of words and images.

In my preface to the Ph.D. dissertation version, "Doe in Heat: A Critical Biography of the Bengali Poet Jibanananda Das," I had written:There were many others over the past two decades who have helped me to better understand Bengali literature that I might transform Jibanananda's life into a book. Invaluable were the many evenings in Calcutta spent with Buddhadeva, Jyoti's father-in-law, discussing everything from poetry to politics to the price of tea--especially and always poetry.

Jyotirmoy Datta first got me interested in Jibanananda Das and his poetry. At that time Jyoti was teaching at the University of Chicago, having just completed a period of residence at the Writers' Workshop in West Branch, Iowa. Then while I was in Calcutta during 1969 and 1970, Jyoti and his wife Mimi and their two children, Teeteer and Gogo, welcomed me warmly and constantly into their always open home. It was at Jyoti's, 202 Rash Behari Avenue, that I found my first and lasting place of adda--the life-blood of social and intellectual intercourse in Calcutta.

It was my present colleague at the University of Chicago, Professor Dipesh Chakrabarty, who in the course of a conversation noted with regret that my reference to the adda--what we might refer to now as the "du-sho-dui [202]-Naktala adda"--had been deleted in the published version of my book on Jibanananda, a casualty of editing concision. Dipesh had read both "Doe in Heat" and A Poet Apart; he himself has also written on adda, a chapter in his forthcoming book. Today, as I gaze back a full thirty years, I can reaffirm my earlier statement made in the dissertation: With Buddhadeva and family and their many friends I did indeed pass some of the most pleasurable times of my life, participating in adda.Adda is translated as a combination of "bull-session," "kaffee katsch," and "soiree," but the actual nature of the beast is accurately conveyed by none of the above semi-synonyms. There are some who believe that the adda is unique to Bengal. Jyoti's father-in-law, Buddhadeva Bose, was even motivated to write an article describing what an adda is (see Buddhadeva Bose, Prabandha samkalan [Collected Essays] [Calcutta: Bharabi, 1966]). And it was at Buddhadeva's new place in Naktala, a neighborhood to the extreme south of Calcutta, that I found my second and equally stimulating adda locale. Often the two spots blended into one. Kavita magazine, without a doubt the most significant Bengali poetry journal of this century, had been edited by Buddhadeva from 202 Rash Behari Avenue. And once in a while Buddhadeva would return to visit his son-in-law and family there. But more frequently we all would congregate out at Naktala for a rousing evening of adda. With Buddhadeva, who passed away in 1974, and his lovely wife Protiva and their family--daughters Mimi and Rumi and son Pappa--and all their friends, I spent some of the most enjoyable times of my life.

During the very early part of 1971, I had decided to translate Buddhadeva's Rain through the Night (Rat bhore brishti). As I cast my mind back thirty years to examine my own motivations for taking on the challenge of rendering this Bengali novel into English--when I probably should have been concentrating my energies on the Ph.D. dissertation and Jibanananda--it is hard for me to be sure what moved me most. While still in Calcutta, I had, of course, known of the case brought against this work of literature on the grounds that it had violated obscenity statutes within the Indian penal code. Not only did I know of the case in some detail, and kept abreast of events concerning it via the du-sho-dui-Naktala adda, but also I participated, although quite peripherally, in the actual court proceedings at one point. The eminent educator and scholar Dr. Manoshi Dasgupta was scheduled to testify in court the following day, both as a character witness for Buddhadeva and as a respected literary critic who could speak to the merits of the novel. Pappa had to be excused from escorting her to court because of binding obligations at Jadavpur University, where he taught in the Department of Comparative Literature, a department that Buddhadeva years earlier had been instrumental in establishing and which was then the only department of comparative literature in the entire South Asian subcontinent, if I am not mistaken. Subir Raychoudhury and Amiya Dev, both friends of the family and members of the Comparative Literature faculty, were likewise unavailable to serve as her escort. Debabrata Ray, close friend of Pappa's and of mine, may have been engaged in documentary film shooting somewhere. In any case, he too could not accompany Dr. Dasgupta that day, nor could Jyoti, who had pressing matters to attend to elsewhere. The honor--I thought of it as an honor--of picking her up in an ordinary taxi (a black Ambassador, no doubt), going with her to court, and escorting her back to the women's college where she served as principal fell to me. The experience proved quite pleasurable, as I knew it would. The court and its legal majesty in combination with petty bureaucrats, clerks of all manner, going hither and thither, and bundles of documents, each bound in its own red tape (ribbon), instilled in me both awe and curiosity at the same time. I was simply part of the audience. I had no part to play in the proceedings. Nevertheless, it was thrilling to be present for the drama. And I could reflect upon Jibanananda's comparable situation, when he came in for ridicule (not legal action, thank goodness) by Sajanikanta Das and the coterie associated with the journal Sanibarer Cithi when they took him to task for such innocuous expressions as "doe in heat" in his poem "In Camp (kyampe)."

Rat Bhore Brishti,

Cover; 1990 edn.I seem to recall that on that day Karunashankar Ray, the barrister representing Buddhadeva, was interrogating the man who had initially brought the case against the novel for being obscene and without redeeming literary merit. My recollection--and I am certain it is not accurate with respect to the details--is that Karunashankar had asked the witness whether he had read Tagore, something which any self-respecting educated Bengali could be expected to have done. When the witness replied in the affirmative, Karunashankar then asked him to tell the court the plot of Tagore's novel My Little "Eyesore" (Cokher bali) or, if not that, then of The Home and the World (Ghare baire). The witness could do neither. The thrust of the questioning, I presumed, was to expose the witness' total ignorance of Bengali literature and thereby impugn his credentials as one who could judge whether any work of literature--the novel Rain through the Night, in particular--had literary merit or no such qualities whatsoever. Had the witness demonstrated a familiarity with either of these works, I believe Karunashankar would have pressed him to evaluate the character of Binodini and Bimala and compare those two with Maloti, whose marital infidelity seemed so obscene to this plaintiff. But the cross-examination ended there for that session, if I remember rightly. Manoshi Dasgupta, I believe, testified that day also. And, I am certain she did an impressive job of defending both Buddhadeva and his literary creation. But somehow, for some reason, it was the courtroom skills of barrister Karunashankar and the way in which he embarrassed Buddhadeva's accuser that remain a part of my selective memory today, thirty years after the fact.

I was not in Calcutta when the verdict was handed down. It went against Buddhadeva. I quote Jyoti's words on the conviction, printed in the magazine Evergreen Review:

The Bengali poet Buddhadeva Bose was convicted on December 19, 1970 of obscenity by the Additional Chief Presidency Magistrate of Calcutta, Police Judge Barrari, after a trial lasting a year and a half which included seventy days of hearing. The trying judge not only heaped indignity after indignity upon the sixty-three-year-old writer--such as making him stand in a wire cage, ordering a search for the confiscation and destruction of all copies of his printed book, and destruction of the manuscript--but also refused him leave to appeal. Bose's book has been banned and his life is in danger. (Evergreen Review, 91 [July 1971]: 61)

Why did I decide to translate this novel? Thirty years after the fact, I know I am going to be inaccurate in my reconstruction of the answer(s) to that question. Nevertheless, I shall try. I was, of course, upset by the conviction. I wanted to present to a much wider audience--the English-reading audience worldwide is clearly much larger than the Bengali-speaking audience--this work of fiction. I wanted it out there in the larger public domain for readers to be able to judge for themselves whether the charge of obscenity had any merit whatsoever. I wanted it out there so that others could appreciate this novel qua novel. I wanted to do something for Buddhadeva, who had been so kind and so helpful to me during my year and a half of residence in Calcutta while I was engaged in research on Jibanananda. And though this may seem like an odd way to show my affection for him, translating his novel was, indeed, from my point of view, a demonstration of my love and respect for the man. I wanted to be involved with something both current and Bengali.Shortly after I arrived back in the States upon completion of my research on Jibanananda, a devastating cyclone struck East Pakistan, in November of 1970. Within days of that, I received a telegram from the Peace Corps office in Washington, D.C., asking if I would be willing to return to East Pakistan as part of a cyclone and flood relief mission. (I had served as a Peace Corps Volunteer at the Barisal Zilla School from mid-1963 to mid-1965.) I answered that I would. Before anything further developed, however, another message came from Washington saying that the government of Pakistan had declined the Peace Corps' offer to help in relief efforts on the grounds that East Pakistan needed no outside assistance. With hindsight, we know that the Pakistan government's (i.e., West Pakistan's) treatment of relief efforts in East Pakistan after the cyclone was one of the several contributing factors that brought about the declaration of Bangladesh's independence and the outbreak of hostilities at the end of March, 1971, resulting nine months later, after a bloody freedom struggle, in an independent Bangladesh.

The Pakistan government had rejected the Peace Corps' offer to send some of us back to East Pakistan where I might have--and then again I might not have--been able to contribute to the relief effort following the November cyclone. Exactly how translating a novel under legal siege equates to--or serves as a surrogate for--participation in cyclone relief efforts in eastern Bengal escapes me now. In early 1971, when I was still in my twenties, albeit very late twenties, the logic of that equation may have seemed more obvious and compelling. Moreover, I wanted somehow to remain a part of that du-sho-dui-Naktala adda. Admittedly, one cannot participate in an adda from half way around the world. Adda is something interactive; it is something spontaneous; it requires your presence. How could I, in Chicago, be a part of a Calcutta adda? The simple answer: I could not. Be that as it may, I believe, as I reflect upon those days more than thirty years ago, that one of my motivations for translating Rain through the Night was that urge to be there, to be vicariously a part of the adda.

I began translating the novel without informing Buddhadeva of my intent. I am sure I was hesitant, not knowing whether I would be able to complete the task to my satisfaction, or his. By the end of the Bengali year (April 14th), I had finished the initial draft. It was slightly before this time that I received the first of the following letters from Buddhadeva, informing me that another student from the University of Chicago working under Edward C. Dimock, Jr., had begun work on that same novel. In what follows, letters that I received from him from 1971 through 1973, I shall let Buddhadeva speak pretty much for himself, though I shall provide commentary now and then to expand upon certain items. Except for the final letter, in which he corrects a misconception I had about Tagore and prose poetry in Bengali, all the letters in one way or another pertain to Rain through the Night. By the time of that last letter, I have disengaged from the translation of his novel, which was about to be published, and resumed my work on Jibanananda. Even then, or maybe more so then, our relationship--him, ever helpful, me, the beneficiary of that help--was strong. He died the following year, 1974, far too young, still in his sixties. I missed him then; I miss him yet.

Letter #1364/19 Netaji S. C. Bose Rd.

Calcutta 47

April 9, 1971

Dear Clint:

I recall you mailed a set of Kavita for Chicago University Library and I hope they have safely arrived. Now if the university decides to acquire the copies, it would be very useful for me to have the money at this time. The reason is that I am being harried by the income tax people who are double-taxing me on my American income in 1965--and my arrears in tax come to a murderous amount. I leave it to you and Ed to fix the price of the set. Please make the check payable to Protiva Bose and have it sent per registered mail. Clearance would be easier if you make it a draft on the Calcutta branch of some American bank.

Ruta Pempe has shown up in the meantime. She lives in a village in Midnapore and wears shell bangles and iron bangles so as not to look an outsider. She has shown me a few pages of her translation from Rat Bhore Brishti--it is promising.

All the best,

Yours affectionately,

(sd.) Buddhadeva Bose

Buddhadeva Bose

Buddhadeva had allowed me to assemble a nearly complete set of the quarterly Kavita and the annual Baishakhi from his personal collection to sell to the University of Chicago library. He himself had but one complete set in his possession at the time. Ed (Edward C. Dimock, Jr., my professor) and I arranged for our library to purchase those materials at a rather good price. Furthermore, Buddhadeva kindly gave me gratis a less complete set of Kavita, including the invaluable special Jibanananda issue. In 1965, he had been a visiting professor of comparative literature at Indiana University.Ruta Pempe began graduate study several years after I had entered the program. Under Prof. Dimock's tutelage, she had chosen as her research topic a study of Buddhadeva's novels. That dissertation, as yet unpublished, is entitled "A Genetic Structural Interpretation of Novels by Buddhadeva Bose" (University of Chicago dissertation, 1976). Chapter IV, "Ventures through Anguished Loves and Rat Bhore Brishti," contains a very perceptive reading of Rain through the Night. Other chapters examine the four novels Mowlinath, Kalo Haoya, and Golap Keno Kalo.

Letter #2364/19 Netaji S. C. Bose Rd.

Calcutta 47

May 22, 1971

My dear Clint,

I've delayed answering your letter in the hope of acknowledging your remittance, but as of date there has been no news from National & Grindlays and it's a full month since you sent the letter. Jyoti says that even bank transfers go astray sometimes, and we are beginning to wonder whether some mishap might not have overtaken your remittance. Please make inquiries at the bank through which you sent it, and let us know the results. We hope the money can be recovered, after all.

I planned a long letter, but today I have to be brief because I'm leaving for London tonight on an invitation from Air India to fly by their newly augmented Jumbo jet. It will be a 4-day trip in London--I'm trying to make Paris. For a few days--will be back in Calcutta in early June in any case. Ruta is "heart-broken" (Mimi's phrase) to hear of your having translated the whole of "Rat bhore brishti"; she has finished the first section and now intends to wait until we receive your mimeograph. I hope the copy will have wide spaces and margins, so that I can put down my comments and suggestions.

Your money, when it comes, will be of great use in paying off a part of my debt to the Govt. of India; you have set the price quite high, and I warmly thank you and Ed and whoever else is involved. I hope these old copies will be of some use to some one at some time.

We all knew Terry Shore and loved him and we are all glad to know he's now studying Bengali at Chicago. Maybe we'll see him in Calcutta sometime. Sterling Steele passed through recently--he's going for a year to Berkeley to study statistics. Wonderful to see our friends and to hear from them--rays of sunlight in this darkening world. I'll write a long letter later. All the best

(sd.) Buddhadeva.

P.S. Please do not address me "Dear Sir".

Terry Shore studied Bengali at the University of Chicago for a couple of years but did not complete his degree here. Sterling Steele worked for the USIS (United States Information Service) in Calcutta and is an avid reader of literature. He spent many an evening with Buddhadeva discussing the world literature they both loved. I had not yet arrived in Calcutta when Sterling was stationed there, but I did get to meet him once, at Buddhadeva's, when Sterling was passing through the city on his way elsewhere.Letter #3

364/19 Netaji S. C. Bose Rd.

Calcutta 47

June 4, 1971

My dear Clint,

On my return from Europe two days ago I found your bank order on my table, so all is well with the money and you need not worry about it. Now I will try to answer some of your queries--well, there were some stone-throwings at our house in April, plus verbal filth hurled by urchins from the alley--all this made the family a little nervous, and there was serious talk of letting out the Naktala house and moving back to Ballygunge. Desultory attempts were made in that direction but they proved abortive. The chances of finding a suitable tenant for this house seems extremely scanty in the present time, also a flat that would be tolerable for us would be very hard to come by unless we agree to half-starve for the pleasure of living in Ballygunge. Luckily, the jeers and brickbats haven't been repeated latterly, this doesn't of course mean they will never be, but on the whole the best thing for us would be to stay put at the Naktala house which after all is spacious and comfortable and can compensate in other ways for the occasional bursts of hooliganism. This whole business has left me somewhat windblown in my mind--for some time I haven't been able to settle down to a long bout of writing, and this last visit to Europe, though very brief, has made me a little more disillusioned about the future of Calcutta and us Bengalis. But family and friends are all well, and that is much under the circumstances, and by tomorrow or the day after I will force myself to start work on a novel I have promised a magazine. My misfortune is I cannot be really happy unless I am engaged on some piece of work, and the happiest moment is when, after great toil, I have finished one somewhat to my satisfaction. But enough of talk about myself.

The house now is fairly full--Rumi has come with her children, Milu arrived yesterday with her baby son, Titir is spending her holidays with us--so Mrs. B. has plenty of company and lots of household chores. Jyoti is planning a housewarming party at his new Jodhpur Park house--I did some canvassing for him in Bombay where I spent a day on my way to London, and in London and Paris I found some of his old friends vastly intrigued by his vegetarianism. I told you in my last letter--didn't I?--that Rumi is well on her way to becoming an American Ph.D.--there are some chances of her getting a job in the Humanities dept. of the Kanpur I.I.T. Calcutta still has its daily killings--prices now are higher than ever with new taxes and the operation of electricity has become as unpredictable as the English weather. This city is illustrating Goethe's great saying, "Thou must do without"--and it's strange to think how much deprivation one learns to put up with or even become accustomed to.

I gave Debabrata your message and I hope he has answered your letter. I did receive your other letter concerning Zbavitel's encyclopedia, I didn't answer because I had no comments to make. One or two new books on Jibanananda have been announced. I'll send you details when they come out. By now you must have got started on your dissert--when you finish it, please consider the possibilities of a Bengali version. The July Evergreen has printed Jyoti's manifesto on Rat bhore brishti--the whole of it--here in Bengal the 10p. campaign, I understand, is fairly successful, but it would be a real headache sending back those 10 payasas if we get an acquittal in the High Court.

Affectionate greetings to you and Ed, and good wishes to other Chicago friends. Everybody here remembers you warmly.

Yours, as ever,

(sd.) Buddhadeva Bose

P.S. I hope Shamsul Bari's family is safe in East Bengal--it is now known that many escaped by fleeing to the villages. A large number of intellectuals have come over to Calcutta--one is (or has been) living with Amiya, another with Uma and Ashin--their housing poses another big problem. There is cholera at the border, and a strange eye-disease is spreading. I read a very hard article on Calcutta in N.Y. Herald Tribune in Paris.

Professor Dusan Zbavitel of the Oriental Institute in Prague, a scholar of Bengali and author of Bengali Literature (Wiesbaden: Harassowitz, 1976) was one of the editors of a three-volume work entitled Dictionary of Oriental Literatures (NY: Basic Books, 1974). The second volume contained entries on South and Southeast Asia, for which I contributed a few lines on Buddhadeva.

Buddhadeva's conviction was being appealed in the High Court. Jyoti at this time had begun a fund-raising--and consciousness-raising--campaign, which he described in his open letter to the Evergreen Review:

We have undertaken to raise the amount of the fine [imposed by the court on Buddhadeva] by making a public collection. We are seeking ten-paisa, or one U.S. cent, donations from people who are willing to risk such a public avowal of their convictions. So fear-ridden is the air of Calcutta that even young writers have refused to appear as defense witnesses for Buddhadeva while others have expressed their willingness to contribute handsomely in money, but have declined to sign and put down their addresses. Of course the fear is mostly in our minds, but it has been quite as paralyzing as real danger. The signature campaign has given those who had earlier chafed against their helplessness and inactivity an opportunity to come out in the open with their beliefs and to confront others with a choice. (Evergreen Review, 91 [July 1971]: 70)

The fear Jyoti speaks of stems from what is known as the Naxalite movement, a terrorist or revolutionary movement--depending upon one's point of view--that took its name from the town of Naxalbari in northern West Bengal where landowners had recently been killed by landless peasants. By 1970, that movement had become very much an urban phenomenon. Again, in Jyoti's words:On the other hand, the political gangs, the Fascist-Naxalite hoodlums, and the little nabobs of Bengal, who are engaged in a murderous struggle for power, for the control of the sewers and alleys of Calcutta, regard every manifestation of independent thought as a challenge to their authority and a threat to their attempt to cow all Bengal into submission. Both the right and the left have declared that it is not hunger and disease and ignorance that are the enemies of the people, but freedom of thought and equality of sexes and originality of dress and book and song. (Ibid., 61)

The crackdown by the Pakistani army on Bengali Pakistanis, its own citizenry, in Dhaka had occurred in late March. By June it was absolutely clear that a war of independence was well underway in East Pakistan. Many Bengalis became part of the Mukti Fauj, later called the Mukti Bahini, or liberation army. Many in the cities, Dhaka particularly, took refuge in the countryside. And many who could eventually crossed the border into India. Since the Pakistani authorities targeted Bengali intellectuals, it behooved them to leave the country. Shamsul Bari, who now serves as Director of the Regional Bureau for South West Asia, North Africa and the Middle East within the UNHCR (United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees) in Geneva, was then in the States and had taught Bengali for a time at the University. His parents lived in Dhaka. Amiya Dev is now Vice-Chancellor of Vidyasagar University; Dr. Uma Dasgupta heads the Fulbright office in Calcutta; her late husband was at one time Vice-Chancellor of Visvabharati University.

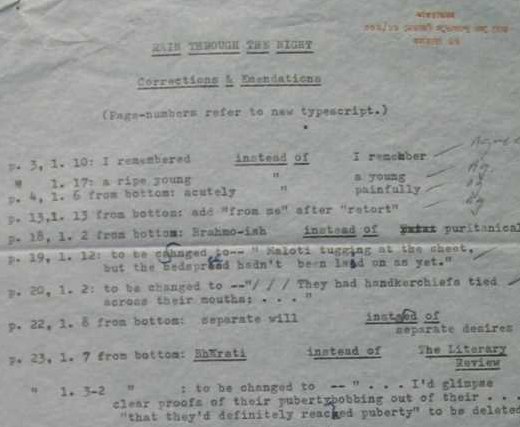

Corrections & Emendations Letter # 4

June 17, 1971

My dear Clint,<

I have received your letter and the translation (both copies), and although I've read only the first 10 pages or so, I think I can give my first reactions. It is fluent and easy to read, the pace is fast, you seem to have managed the long sentences quite in keeping with the tone of the original, some passages struck me as very good indeed. Of course there are a few literals (did you never hear the phrase "hajar hok" spoken? it simply means "after all' and has nothing to do with a thousand or a hundred.) Also, you have rather wandered from the point here and there. But these are minor flaws: you've got the tone, and that's the main thing.

While I enjoyed your colloquialisms, I did feel there is a bit too much of them, I'm not so sure about "thusly", because Malati says "emni kore"--a time-honoured phase. Do you think there is correspondence between the two?

At the moment I am busy writing things for the Puja Specials, and will be so, I expect, until the end of August, so I've decided not to look into your translation until then. The reading will take much time, much labour, for of course I want to compare it line by line with the Bengali, and a number of changes will be unavoidable. I promise to send you a detailed report when the time comes.

I don't think it is legitimate to introduce a metaphor which does not occur in the original, like your using "sardines" for "lepte pinda pakiye jay" (P.22 of R/B/B/): what I mean is that even if the sense be the same "pinda" has a Bengali-ness which must be retained. I am also in favour of giving literal translations of more Bengali idioms: by doing this the translator also becomes a liaison man between two cultures. But of all this, more later.

I am in favour of minimizing footnotes as much as possible, and I do not think words like sari and dhoti and pajama need them at all. "Elixir" for vishalyakarani is all right...I will have to think about "pratham varshar kadam phul"--Supriya has sensed it right (why shouldn't she?), but the phrase would be difficult to translate. (I do not like your "monsoon season"--it is too geographical, non-emotive.)

You are on the wrong track regarding the passages on pp. 159 and 167 of R.B.B. There are no misprints in them; the contradictions are intended. To Nayanangshu (and to many of us) life is both ksamahin and dayamoy, ruthless and merciful--because it inflicts pain, and also makes us forget. At first Malati wants to get the chores done by Kestho, then changes her mind, so as to keep herself busy, I guess, or she might change her mind again. All this is to show the confused and irresolute state of mind with which man and wife are sitting at breakfast table the next morning. Their thoughts drift from this to that, and nothing seems to make any difference.

As for title, I suggest Rain through the Night.

Has Ed looked at your translation?

Ruta did some 12 sheets of typescript, I want to lift one or two phrases from her--I hope neither she nor you will mind.

I handed your letter to Mimi this afternoon. Their new address is: 217-A Jodhpur Park, Calcutta 31. Jyoti's latest in Kolkata is a long piece on Jodhpur Park.

All the best,

(sd.) Buddhadeva Bose

Supriya Sen, now Supriya Bari and living with her husband Shamsul in Geneva, was in Chicago at this time. I relied on her for help with any problems I had understanding Bengali. Her translation, in collaboration with Professor Mary Lago, of Tagore's The Broken Nest (Nastanir) is superb.

Letter # 5

Calcutta 47

Sept. 11, 1971

My dear Clint,

Yesterday I finished reading your translation, comparing it line by line and word by word with the original, admiring all the time the dexterity with which you have handled the long and involuted sentences. My corrections, however, are fairly extensive: they were made, firstly, to correct verbal misunderstandings of the text, and secondly to amend passages where the translation was just literal but did not convey the inherent meaning. And then there were passages which didn't quite catch the tone and so on. I've spent hours ruminating on possible alternatives and I hope the result will be satisfactory on the whole.

I notice you have avoided using the word "God", and I guess you did so on theological grounds. But the "Lord" and still more the "Divine" sounds so artificial and literary, I have substituted the simple and honest monosyllable in many places. The point is that in common usage "ishwar" or "bhagaban" means exactly what "God" does in the Christian world, and we are not writing a philosophical treatise but a novel.

I have also removed some of your Americanisms, by which I mean words which would not be normally understood outside the United States. It being a work in translation, it wouldn't do to make it too "American"--racy, yes, colloquial, to be sure, but at the same time, it should use some sort of "standard" vocabulary so that, if published, it can be easily comprehended in every part of the English-speaking world (including India). This I have found to be the practice in English translations of Russian and Japanese fiction, two areas far removed from the Anglo-Saxon or West-European sphere. Also, the foreign-ness of the book should be stressed a little more; for instance, I'm in favor of making literal translations of Bengali phrases wherever feasible, as, "the skies wouldn't fall on your head", though not "English", would be understood in any part of the world, so there is no need to substitute "the world won't come to an end." *[CBS: The letter is typewritten, but here Buddhadeva has handwritten an asterisk and then handwrote the following at the end of the letter: "I'm trying to say that in translating a foreign work we are also transposing a foreign culture, another way of life, and the more that way of life is brought to view, the more successful the translation."]

What I now intend to do is to copy out my corrections on the second copy, possibly with occasional comments on the reverse. This, again, will take some time, for knowing myself as I do, some further revision of my own work would be inevitable. I think it will be a good idea to return you the corrected copy in installments, so that you can take your time checking and retyping. I think it would be quick work if we can have the final version ready before the end of the year.

Regarding an alternative to "thusly", "and it happened that way" sounds quite all right to me: you just think about it once more.

Gopal Ray's "Jibanananda" is out; in the Preface you are mentioned throughout as a "shaheb", which is rather comical. I expect the author will send you a copy. There is another book--"Jibanananda-Smriti"--a collection of critical essays, which I will send you by slow mail. I hope you are going ahead with your own work at a fair pace.

Allen Ginsberg dropped in the other evening; he's shaved off his beard, and his bald patch is larger than when I saw him last, but the light in his eyes shines as brightly as ever. I told him of the work you are doing on Beng. Lit., he was quite interested. Allen has set to music many of the Blake poems which he sang for us with a harmonium; they are lovely.

Mrs. B. is having bouts of fever and throat trouble, but for this, the family is well--as much as possible under the circumstances. The "obscenity" case is still hanging at the High Court; my little English anthology should be out next month.

Ruta hasn't been [by] for a long time now, Mimi/Jyoti have met her a few times, but I've really no idea what exactly she's doing now. Her 8 to 10 pages of translation are with her, and I don't remember how she rendered "emni kore".

Love to you and Ed.

As ever,

(sd.) Buddhadeva

Allen Ginsberg spent some time in Calcutta, much of that experience captured in his inimitable style in his Indian Journals: March 1962-May 1963 (San Francisco: Dave Haselwood Books & City Lights Books, 1970). He is credited with motivating a group of young Bengali poets who called themselves the "Hungry Generation" (analogous to the "Beat Generation," of which Allen was a prominent member) or just "Hungries," for short. I cite in A Poet Apart his rendering of a portion of Jibanananda's poem "Lighter Moments" (laghu muhurta), for which he gave me permission to reprint only if I indicated that it was an "adaptation," not a "translation." He did not know Bengali.

An Anthology of Bengali Writing (Bombay, Calcutta, Madras: The Macmillan Company, 1971). The International Association for Cultural Freedom holds the copyright for this anthology. My complimentary copy came with a business card from the journal Quest, the name A. B. Shah attached. Buddhadeva and I collaborated on a translation of Jibanananda's essay "On Poetry" (kabitar katha), included in this anthology.

Letter #6

Calcutta 47

Sept. 20, 1971

My dear Clint,

Today I am sending off a registered air mail packet--the first two sections of your translation. I hope you will be able to read my handwriting and, with the help of the notes, gain a fairly clear idea as to why the revisions were necessary. I would, however, request you to have the Bengali book open before you while re-reading the text--this, I think, will give you a better understanding of not only Rat bhore brishti, but also of modern Bengali idiom. Of course I do not claim that I have hit on the happiest expressions in each case; please let me know of possible improvements that might occur to you.

I appreciated your way of juxtaposing the tenses, which does follow the original almost exactly. I have, however, made some changes in that regard, depending on my ear, also on the situation described. I have eliminated some of the footnotes you suggested, but added other ones, such as on the name of the months. I wrote to you before regarding Americanisms, but I have nevertheless retained your "shooting the breeze", and once or twice your "bull session" (phrases I did not know until I read your Ts. and which I spotted only in the Dic. of Am. Slang)--they come fairly close to the spirit of adda, a very important and utterly untranslatable word! I hope, if the book comes out, non-American readers will be able to guess the meaning from the context.

Now the procedure I suggest is this. If you feel happy with my revisions, you may start retyping right now, but if you have questions, please let me have them first, so that we can come to an agreement. I want every sentence in the translation to be approved by both you and me; you will note that in the passages I've rewritten I have retained your words as much as possible. While retyping, please indent every new paragraph, including dialogues, and underline words to be printed in italics. I am in favor of translating titles of book, etc., but felt at a loss to find a word for Bharati ("Goddess of Learning")--perhaps Literary Review would be an approximation. The real headache, however, is Jayanto's magazine, Bartaman, with his misspelling and so forth; I am still thinking of a way to render the whole thing in English.

I have never seen "a little" or "a bit" printed as one word, sometimes "awhile" is or was used, but perhaps not quite in the sense we need here. I do think it advisable to print all such phrases as two words, passim.

I think we should say just "sessions" after Maloti joins the adda, for it is no longer composed of "bulls" only, and then the conversation there is not made up of idle gossip--N. and his friends discuss art and literature and politics, it is something like a salon.

Here's a little anecdote which might amuse you. The other night as we were sitting at supper Kartik said something which I heard as "Shakespeare is banned"! On making him repeat the statement two or three times, I realized our guardians of public morality had swooped on the so-called sex-magazines. Truck-loads of Sundar Jiban, Jiban-Jauban and Sundari and all the rest--their Puja Specials on which enormous sums were invested--were seized by the police and even poor Patiram arrested--so Kartik reports. This reminded me that in the Kallol period there was some witty Bengali who used to refer to Shakespeare as Sex-Pir (pir--Muslim saint)--the Saint of Sexuality, which, if you come to think of it, suits the Bard rather well, and I think it would have been a much more sensible step to banish the mustard-hot Shakespeare rather than magazines which contain nothing more than badly printed pictures of semi-nude women, passages from Kinsey and Kraft-Ebbing, and innocuous little tales under lurid titles.I'm sending you the Jibanananda book by slow mail.

Look forward to hearing from you.

(sd.) Buddhadeva

Despite what he says in the second paragraph of the above letter and what we might have at one point planned to do, the published version of Rain through the Night contains no real footnotes, nothing at the bottom of the page. On page 35, however, there is the following parenthetical insert: "One time in the month of Ashadh (in Bengali calendar corresponding to June-July) it started to rain, and it seemed like it wouldn't stop"; on page 40, "[I]t was the month of Chaitra (corresponding to March-April), moonlight like glistening water, the south wind frenziedly blowing." Chaitra is used four pages later, without the parenthetical explanation, and that is the last time a month is referred to by its Bengali name. Note what Buddhadeva says in the September 11th letter just prior to this one: "the foreign-ness of the book should be stressed a little more; for instance, I'm in favor of making literal translations of Bengali phrases wherever feasible" and that translation is an act of "transposing a foreign culture, another way of life." Ironically, years earlier a comparable situation arose with respect to names of the months and literal renderings and a sense of the foreign in an English translation. Jibanananda had translated his own poem entitled "Darkness" (andhakar) for an upcoming bilingual number of Kavita (1953). Buddhadeva made several revisions, to which Jibanananda took umbrage. I quote part of Jibanananda's reply to Buddhadeva, cited in my A Poet Apart, p. 244:

It seems to me that just as we had to learn the significance of "Lethe" etc., so the readers in the West ought to learn gradually the deeper meaning of Vaitarani, Kirtinasa, and so forth. Kirtinasa carries with it a special suggestion--that particular meaning does not arise in the Ganges, Yamuna or "waters of the earth." I don't believe that the poets in China ever translate specific rivers into English.

In the version of the translation published in Kavita, December and January are indeed used in place of Paus and Magh. The rivers Vaitarani and Kirtinasa each are found once transliterated and once translated into "River of Death" and "River of Mutability." Buddhadeva himself kindly showed me this postcard from Jibanananda, which he still had in his possession.If you change "Paus" into "December," then are you going to change "Magh" (O kokil of Magh night) into "January"? Let the foreign readers learn that Paus and Magh are our winter season; let their ears get accustomed to our rivers, seasons, and various other things. Later they can make the connections. For the time being, how about putting in a footnote?

Kartik worked for the Bose household and lived there, doing the daily food shopping and so forth. He also held a job with the Bharabi publishing house.

Letter #7

364/19 Netaji S. C. Bose Rd.

Calcutta 47

Nov. 16, 1971

My dear Clint,

In October I sent you under registered airmail cover, in two installments, the TS of your translation of RBB, along with my emendations and suggestions. But as of date, I haven't had a sound from you, not even an acknowledgement. Why this silence? Please let me know if the packages arrived in tact, and if you have started working on them. I'm beginning to feel a little worried.

The case at the high court is going badly, even Karunashankar doesn't sound very optimistic. We fear that the book will suffer a temporary death in this country; it will be some solace if it receives a sort of second hand life through publication in another country and in another language.All the best,

as ever,

(sd.) Buddhadeva Bose

(Buddhadeva Bose)

Karunashankar Ray was both the barrister representing Buddhadeva and a friend of the family. He and Jyoti and Subir Raychoudhury attended Presidency College together. I remember that I was slightly surprised the first time I heard Karunashankar and Subir call each other by the tui form of the second-person pronoun. It was then that I realized how longstanding was their friendship.

Letter #8

364/19 Netaji S. C. Bose Rd.

Calcutta 47

Jan. 22, 1972

My dear Clint,

Please excuse this delay in acknowledging the receipt of your comments of my corrections. On glancing at them I felt you are right in many cases, but as yet I haven't had time to check them carefully. For the last two months or more I've been at work on a long essay on the Mahabharata, and this will keep me busy till the end of this month. I will return you your correction sheets, with my suggestions in about a month's time from now.

I recall your suggestion regarding the inclusion of documentary material on obscenity, if the book is published in the U.S. It's a good idea, but I think those essayistic writings should form a separate book aimed at legal and sociological researchers, and the novel be published simply as a novel, meant for the general reader, with no more extraneous material than a short note on the author. But let us have the final version ready before we think of such things. I warmly support the idea of getting the whole book read by an American writer (why not Ed?) before it is submitted to a publisher.

Jyoti has given up his Jodhpur Park house; the family is for the time being located here at Naktala--there is some talk of their going abroad in April. Currently, Jyoti is dividing his time between Calcutta and his riverside village where I believe he's building a clay cottage.

I have a very sad news to give you--our dear friend and colleague David McCutchion is dead. He was carried off by a sudden and extraordinarily virulent attack of polio, he was finished with(??) 24 hours of the appearance of the first symptoms. The most shocking thing is that his book on Bengali terracotta temples, for and (??) which he had toiled incessantly over the last 10 years, and which would have been the book on the subject, will remain unwritten for all time. He had finished collecting his material, had taken thousands of photographs and numerous sheets of notes, had definite plans for going to England to do the actual writing--and just then death takes him away. What can be more cruel and more unjust? Please give this news to Ed and other friends who knew him or about him. This is a very serious loss for the world of Indological scholarship.

Our best wishes for the new year to you and all our Chicagoan friends.

As ever,

(sd.) Buddhadeva

(Buddhadeva Bose)

The Mahabharata reference in the first paragraph pertains to writings on this great epic of internecine war that he produced during the fall and winter of 1971 and 1972, a period when the Bangladesh war of independence raged, then came to a conclusion, in mid-December of 1971. Buddhadeva tells us in the preface that his profound interest in this topic, however, came from a course that he had taught at Indiana University on the comparative study of Indo-European epics--the Iliad, Odyssey, and Aeneid, and the Mahabharata and Ramayana. These writings on the Mahabharata were published first in Desh during 1972, in 18 installments (the Mahabharata war itself lasted 18 days and the Mahabharata epic is divided into 18 books or parvas), and then as a separate book, entitled Mahabharater katha ("On the Mahabharata") (Calcutta: M. C. Sarkar, 1974). Sujit Mukherjee has done a marvelous translation into English of that book under the title The Book of Yudhisthir: A study of the Mahabharat of Vyas (Hyderabad: Sangam Books, 1986).

Mahabharater Katha, and

The Book of YudhisthirConcerning material on obscenity and the law and Rain through the Night, I assembled some information in a paper entitled "Against Buddhadeva Bose's Bengali Novel There Was Hardly a Case," which I presented at the 4th Annual Conference on South Asia, Madison, Wisconsin, 1975.

Due to David McCutchion's lamentable and most untimely death, his own comprehensive writings on the subject of Bengali temples, "the book on the subject, will remain unwritten for all time," as Buddhadeva says. Fortunately, however, much of his research has been published and is, therefore, available to us. See George Michell, ed., Brick Temples of Bengal : From the archives of David McCutchion (Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press, 1983), as well as David J. McCutchion, Late Mediaeval Temples of Bengal : Origins and classification (Calcutta: Asiatic Society, 1972).

Letter #9

Calcutta 47

April 19, 1972

My dear Clint,

Mr. Wellington Calderia of Hind Pocket Books has written me to say he is interested in publishing an English translation of Rat bhore brishti. He has also mentioned "a friend of mine in Chicago" who has made a translation.

In my answer I have said he must publish the book complete and unexpurgated, if at all. Other conditions: British and American rights and translation rights from the English into other languages to belong [to] the author and translator. I have also inquired about his business terms.

Hind Pocketbooks also publish an Orient Paperback series; I have seen their books advertised, I believe they are fairly high up in the Indian English book trade. If they agree to our conditions I think it would be a good idea to accept their offer. (I have also said, of course, that should there be trouble with the law, the publisher will bear all expenses, etc.) I have given Mr. Calderia your address and I expect you would hear from him before long.

Whether or not this proposal works out satisfactorily, it is high time we get ready the final version of the translation. Very soon I will go through your correction sheets and send you my views on them. They are mostly minor points, which can be settled easily. After this is done, I hope it won't take much time to have it retyped.

Here the whole family (including the Dattas) is taking a course of anti-rabies injections, following the death of a house-dog. But for this, things are going fairly well. Mimi is looking for a flat in central South Calcutta, but landlords have become more rapacious than ever and it may be some more time before she can find a suitable place. It might interest you to hear that there is a proposal for making a Hindi film out of RAT BHORE BRISHTI, but I'm not sure it will come to anything.

Love,

Yours, as ever,

(sd.) Buddhadeva

This is the first mention of the anti-rabies injections, which will sadly prove disastrous for Protiva Bose.

Letter #10

(letterhead stationery, in Bengali)

Kavitabhavan

364/19 Netaji Subhasacandra Basu Road.

Calcutta 47

(Buddhadeva sent me six pages of corrections/suggestions, followed by a brief note; I shall cite only a few of those corrections/suggestions, to give a flavor for the type of concerns he had with the translation, and then reproduce his brief concluding note in full.)

p. 8 "getting a taste of blood"I attempted a literal rendering of the Bengali, (ami takhan natun [sic: sabematra] rakter swad peyechi), knowing full well that English has a different connotation. I just took a chance in case my intention came through. If you think it absolutely doesn't, you must contrive some other metaphor to suggest sexual experience--a flat statement won't do.

p. 9 "good wife and daughter-in-law"

(We settled on the following wording: "I had just felt what it was to be a woman.")My objection is that "daughter-in-law" doesn't occur [in] the original, although the idea is implied. You surely know how weighty a word 'bau' (bau) is--it includes "wife" and "daughter-in-law" and "housewife" and other things as well. It may be a good idea to use the Bengali word and add a footnote. In that case we can repeat "bau" in some other passages where we have said "wife". What do you say? (Maloti uses stri when she means just "wife".)

p. 10 [13]

(Our eventual wording: "Becoming a bahu (wife, daughter-in-law) made me very happy at first; after our marriage I tried to be a real good wife and daughter-in-law." The word bahu seems not to have appeared again in the novel.)The irony of sarbajwarahara maduli is not conveyed by abstract words like "disease" or "sickness" or "illness". "Fevers" gives an image, it has a pictorial quality which brings it closer to the Bengali. I suggest you retain it.

p. 83, line 5

(Our eventual wording: "[P]arents can't help but get anxious when they see some young man becoming very friendly with their unmarried daughter, yet once she's married they cease to worry for the rest of their lives, as if marriage were some guaranteed charm against all fevers!")

. . . .rekhe dao tomar bibek! is a blunt and stinging utterance, but "let's leave aside your conscience, if you don't mind" (the best of the four [that I had suggested]) conveys only the sense but not the tone of the original--the clause "if you don't mind" (without which the sentence hangs limp) adds a touch of irony but weakens the impact at the same time. "rekhe dao" means the thing is not even worth considering, it implies a rude and abrupt dismissal in which there's neither irony nor ambivalence. Please try to think of an equally violent phrase in English, without any additional, modifying clause. "Let go" seemed to me to have that quality of abruptness.

Dear Clint:

I'm opposed to using "damn" or "damned" in any context whatsoever, for the idea of damnation is totally foreign to the Hindu mind. "Go to the blazes" is acceptable, however, for Bengali has "cunoy(culoy??) yao!"

(Our eventual wording: "The heck with your conscience!")

I'm sending this with Ruta Pempe who is going back to America. Please write me soon about the points which still remain debatable. I hope your final version will be ready by June, and then we can begin to look for an American publisher.

I've written these notes in a hurry and I hope I haven't overlooked any of your questions.

Love,

(sd.) Buddhadeva

May 1, 1972

P.S. Hope you can read my longhand.

Letter #11

Calcutta 47

May 23, 1972

My dear Clint,

I got your letter a minute ago and am writing back at once. Welling Calderia is keen on having a copy of your uncorrected TS, and I think you'd better send him one, so that he can take legal opinion and come to an early decision. He sounds eager and agrees to all my proposals; he suggests an addition of 8,000 or 10,000 and offers a royalty of seven and [a] half p.c. to be divided between author and translator, but I will try to raise this to 10 p.c. when the time comes. Let us try Calderia first, if negotiations with him fall through, you can then get in touch with Orient Longmans.

Have you heard from Asok Gupta of Vishwa-Bharati Films, Bombay? He, too, wants a copy of your translation, though I do not understand why an English version should be necessary for the purpose of making a Hindi Film.

It should not take months to get ready the final version, for Ruta Pempe promises to hand you my final correction sheets in early June, and unless you are heavily pressed you can retype the whole thing at once.

I refrained from giving you news of Protiva Bose because the news is dismal. She was struck down with paralysis after the tenth anti-rabies injection--this happened a month ago and she is still chained to her bed. The Bose family passed through hours and days of gloom, but now it seems she is slowly responding to physio-therapy--even so, recovery will be a long process and might take several months more. We have to wait with patience and hope: that's all.

Meanwhile, there are the usual Puja Number commissions; I've to produce some quantity of fiction by the middle of August, though at the moment there isn't a single idea in my head which can be spun into a novel. Life is difficult, making a living more so.

Love,

(sd.) Buddhadeva Bose

P.S. I think Sujit Mukherjee means the ms of your translation--his thought is that what is obscene in Bengali may not be found so in English--which, to our great misfortune, is true of the law in India.

Protiva Bose wishes me to add that she is glad to hear of your kind thoughts for her.

I do not recall ever hearing from Asok Gupta of Vishwa-Bharati Films.

Protiva Bose's afflictions remain with her to this day, though she has had an extraordinarily productive life and has truly surmounted her physical disability.

Letter #12

(letterhead stationery, in Bengali)

Kavitabhavan

364/19 Netaji Subhasacandra Basu Road.

Calcutta 47

September 6, 1972

My dear Clint,

I've been working hard all through the summer to meet my Puja number commitments, hence this delay in answering your letter of July 10. I am sorry I had overlooked one of your query-sheets in the batch I sent with Ruta Pempe. Here are my answers to your questions:

(There follows a page and a half of corrections/suggestions; the letter then resumes.)

I hope it will not be very long before you finish typing out the final version. Please send me a copy by registered mail.

Have you heard from the Delhi publishers in the meantime? I haven't; I suspect they have been deterred by their legal adviser. However, I do think an American edition is feasible. I think it would be a good idea to try James Laughlin of New Directions: I knew him well at one time; his daughter Leila (like you, one of Ed's students) translated a couple of my stories while she was in Calcutta. Knopf, who specializes in translated foreign novels, is another possibility; maybe you can think of others. The book should be introduced as one banned for obscenity in the country of its origin; the few lines in Evergreen may serve to introduce the author. Once it is available in English, it may also appeal to publishers in other European languages.

News of Protiva Bose is not as good as I would have like(??) to send. Now, after more than 4 months of treatment, she can sit up in a chair with others' help; the use of her hands is partly restored (she has even written a few stories for the Puja numbers)--but the day of her complete recovery still seems to be far. We need all the patience in the world.

All the best,

As ever,

(sd.) Buddhadeva Bose

James Laughlin was the founder-director of the publishing house New Directions. In 1962 he brought out J. C. Ghosh's translation of Bankimcandra Cattopadhyay's Krsnakanter uil-Bankim-Chandra Chatterjee, Krishnakanta's Will (Norfolk, Connecticut: New Directions Books, 1962). Previous to that, he had republished an anthology of Bengali literature in translation entitled Green and Gold: Stories and poems from Bengal, edited by Humayun Kabir, with Tarasankar Banerjee and Premendra Mitra as associate editors, first published in 1957 by Asia Publishing House (Bombay) and then, subsequent to New Directions, by Greenwood Press, Publishers (Westport, Connecticut, 1970).

The reference to "Evergreen" is to the Evergreen Review and Jyoti's appeal published there, from which I have cited above.

Letter #13

(letterhead stationery, in Bengali)

Kavitabhavan

364/19 Netaji Subhasacandra Basu Road.

Calcutta 47

December 28, 1972

My dear Clint,

It was a pleasure to go through your new version--now the novel reads very well in English and has caught the style and rhythm of the Bengali. Nevertheless, I noted a number of minor discrepancies and felt rather dissatisfied here and there, also tracked a few misprints. Hence the enclosed corrections and emendations which I have made for the sake of greater accuracy, or to elicit the sense of the original (which is not always conveyed by literal-ness), or to achieve what seems to me a little more euphony. You can carry out most of these corrections with neat handwriting, and sometimes by printer's signs--it should not be necessary to retype except where new footnotes have been added. I hope you will not mind this little trouble, for I'm tormented by what Edgar Poe called the "demon of perfection", and I do not want the least little flaw to remain so long as we can help it. As you will note, I've accepted your suggestions re. p. 107; the other changes in tense I find quite in order.

Hind Pocket Books have sent me their agreement form for signature. Unfortunately, it is not acceptable in toto--for instance, they want me to indemnify them in case of legal action, which is impossible, it must be the other way about. They also want 50 p.c. rights on translations from English into other languages, which I do not think is legitimate. I must write them a longish letter after I have finished this, and I will of course let you know the outcome. Please do not commit yourself in any way if they write to you direct in the meantime.

One little point. I requested an advance of Rs.500/- on my royalties, and to this Hind seems agreeable. Do you want any advance too? If you do, we can go halves on the Rs. 500/-, I don't think Hind would fork out more by way of advance. You need not send them that Evergreen bit right now, let us wait until the agreement is executed.

Hind offers 7 1/2 p.c. royalty and six free copies (to be divided between author and translator); I will request (??) royalty and 5 plus 5 free copies. Because of lower production cost and smaller sales, royalty rates in India are higher than in the West.

Pp. 93-94 is okay.

Please let me know if either Laughlin or Bonnie Crown has responded. If you have any comments on these corrections, please let me have them soon. I want to incorporate them at this end in the press copy.

I was wondering if it wouldn't be advisable to use British spelling idiom (for instance p.p. got instead of gotten) in the Indian edition. What do you say?

News on the home front is not as good as might have been. Mrs. B. is a great deal better, but even now, in the eighth month of her illness, her feet remain out of action. Three weeks ago she sustained a minor fracture which is taking its own time to heal. The good thing is that mentally she is brave and remains as cheerful as possible under the circumstances. Another unfortunate thing is that Naresh had a rather severe heart-attack; he's been lying in a hospital for about 2 weeks now, still completely bedridden, and may have to be there another month. You and Ed would be able to imagine how distressing this situation is for the Bose family, for you both know how much Naresh means to us. He is receiving the best medical aid available here and the period of crisis is past, but convalescence will evidently be long and henceforth his life will have to be rather restricted.

We haven't had any sound from Sterling Steele for ages; I'm glad to know Ed met him. It appears Jyoti's American trip has been cancelled; he's now working with Hindusthan Standard as a free lance. Recently I had a short visit from David Kopf and spoke to Len Gordon on the phone.

I mustn't forget to tell you that at last I've straightened things out with the publishers of the little Anthology for which you and I contrived a translation of Jibanananda's essay on Poetry. You will be entitled to a free copy and maybe a small payment, but it will be quite some time before they reach you.

How is your own dissertation going?

With best wishes for the new year to you and Ed and other Chicagoan friends, from my wife and me and the family,

as ever,

(sd.) Buddhadeva

It would be a good idea to prod American publishers for paperback also, in case negotiations with Hind fall through.

James Laughlin, as noted above, ran his own publishing house, New Directions. Bonnie R. Crown was the director of publications for The Asia Society, a New York-based organization. She had been, and continued to be, supportive of publishing literature from South Asia. In the preface to Edward C. Dimock, Jr., et al. The Literatures of India: An introduction (Chicago and London: The University of Chicago Press, 1974), the authors give thanks to Mrs. Crown "for her support, but also the organization that she represents, The Asia Society, for financial assistance." There was reason to believe that we might find some financial assistance in the form of a subvention from The Asia Society, had we located an American publisher.

Dr. Naresh Guha was at that time chairman of the Department of Comparative Literature at Jadavpur University. He had been taken on by Buddhadeva as the assistant editor of Kavita magazine in its final years. The two men, Buddhadeva and Naresh, remained very close. Naresh survived the heart attack and has lived an active and fulfilling life since then.

David Kopf had been one of Edward C. Dimock's very first students of Bengali at Chicago. He is the author of British Orientalism and the Bengal Renaissance: The dynamics of Indian modernization, 1773-1835 (Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California Press, 1969) and The Brahmo Samaj and the Shaping of the Modern Indian Mind (Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press, 1979). Leonard A. Gordon is the author of Bengal: The nationalist movement 1876-1940 (New York: Columbia University Press, 1974) and Brothers against the Raj: A biography of Indian nationalists Sarat and Subhas Chandra Bose (New York: Columbia University Press, 1990).

The anthology referred to was, as mentioned above, An Anthology of Bengali Writing.

Letter #14

Calcutta 47

January 6, 1973

My dear Clint,

I hope you have received my recent letter with the final emendation sheets. Hind Pocket Books wants me to compensate them in the event of a lawsuit; to this I simply cannot agree (as, I assume, you would not either), and it seems that my negotiations with them might fall through, after all. Evidently they are allured by the stamp of "obscenity" but are not prepared to take full risks, which does not seem to me reasonable.

I expect we would run against this difficulty with any publisher in India, so I think you should at this stage negotiate with American publishers for both hard cover and paperbacks (or either-or as the case may be). An American publication would at least be safe from this "obscenity" racket, and should be financially more advantageous. The thought of another lawsuit is so horrifying to me that I am inclined to drop the idea of an Indian edition--until times change.

Will you please try Grove Press and Knopf? I think all likely avenues should be explored.

I expect you will have some copies xeroxed after the final alterations have been made. When they are ready, will you please send a copy to each of the following addresses given below? Darina Silone, the Irish-born wife of Ignazio Silone, the novelist, is a personal friend of mine; Mr. Erdmann is an enterprising publisher who sponsored my volume of Rilke translations and is interested in translating foreign literature in German. Through them, I want to try if Italian and German translations made from the English may be published. Mrs. Silone is an Italian-English translator herself and has a wide circle of friends among the literati. I will write to both of them when your xeroxes are ready.

Please let me have news from you soon.

As ever,

(sd.) Buddhadeva

Buddhadeva Bose

I had a nice new year's card from Ruta Pempe. Please give her my warm wishes when you see her.(over)

(1) Mrs. Darina Silone

Via Villa Ricotti 36

Rome, Italy.

(2) Mr. Horst Erdmann

Horst Erdmann Verlag

D7400 Tübingen (Postfach 1380)

Hartmeyerstraße 117

Germany.

<./blockquote>I approached both Grove Press and Knopf but without success.

Letter #15

<.blockquote> Calcutta 47

March 14, 1973

Dear Clint,

I had almost given up Hind Pocket Books, but at last there is sound from them. They agree to my conditions, so now we can get the book going. I am quoting below their exact words for you convenience:

"Dear Professor Bose:

Sorry for the delay in replying to your letter of February 12th regarding the contract for your RAIN THROUGH THE NIGHT. I am pleased to tell you that we would be happy to agree to (a) deletion of the clause in our printed form which binds the author to indemnify the publisher for legal action etc. (b) addition of a clause to say that in case of a legal action for obscenity the publisher will take entire responsibility for it. . . ." The letter is dated March 8 and is signed by D. N. Malhotra, Managing Director of the firm.

After the words "entire responsibility for it" I will suggest the addition of "including legal and incidental expenses". In an earlier letter I requested a royalty of 10 p.c. and 10 free copies, to be shared equally by you and me, and (since you do not want any advance) an advance payment of Rs500/- from my share. When you receive the contract form from Hind, please check that all the conditions are there.

Jyoti read out to me the lines you wrote him concerning RBB. I expect I received the letter you mean, but I didn't write back because I was waiting to hear from Hind. Please rush a revised fresh TS to Hind as soon as possible (with American spellings altered to British), and xeroxes to Mrs. Silone and Mr. Erdmann. I will write to Rome and Tübingen as soon as you tell me that the copies are on their way. I hope you can also send me a xerox for my files.

Mrs. D.(??) should soon able to stand up with the help of calibres and a stick--at least that's what the doctors are hoping. We are now running the tenth month of her illness.

Best wishes,

as ever,

(sd.) Buddhadeva

P.S. Regarding your queries on my last corrections, please do as you think best in the final version.

Letter #16

Calcutta 47

7 May, 1973

My dear Clint,

So at last the matter is clinched between us and Hind Pocketbooks. Judging by the samples they have sent me, it won't be a particularly elegant production, but at least it will be in book form and your labour not altogether wasted.

Eight or ten days ago the case came up at the High Court. I was requested to put in an appearance--Karunashankar said their Lordships wanted to "have a look" at me--and I guess he was right, for I was asked no questions at all either from the bench or the bar. The older of the two judges seemed much bothered about adultery, our good K.S. [Karunashankar] met his points admirably, and then I heard the same senior judge making most flattering remarks about the book--"beautiful, poetic, surely no bat-tala production!"--and so forth, all in my presence, which gave me the evil foreboding that the book will be condemned once again. However, we do not yet know.

The revised TS came right through, but there was no message with it. Have you sent out copies to Darina Silone in Rome and Horst Erdmann Verlag in Tübingen, whose addresses I gave you? If you have not, will you please rush them soon? The other day I had a note from Darina--it seems she had heard about the case and was worried on my behalf--I'm writing to her suggesting an Italian version, and I hope she'll respond. On hearing from you I'll write to Mr. Erdmann and also try one or two other friends in German.

Mrs. B. is now at a stage where she is practising walking with the help of calibres and parallel bars. But recovery will still take long--nobody knows how much longer it will take. The good thing is she has great courage and mental strength. That helps.

How is your book on Jibanananda going? Any news of Ruta Pempe?

Please give my greetings to Ed and other Chicagoan friends.

Love,

Yours, as ever,

(sd.) Buddhadeva

P.S. I will ask Hind Pocketbooks to send me a set of proofs. Do you want them too?

"Bat-tala" refers to cheap publications of Bengali literature, produced in a particular neighborhood in north Calcutta. Bat-tala productions date from the 19th century and were sometimes of a somewhat lascivious nature, for example, versions of the Bidya-Sundar tale wherein Prince Sundar from southern India comes to the town of Burdwan in Bengal and tunnels under a wall and into Princess Bidya's chambers to engage in premarital sex.

Letter #17

(letterhead stationery, in Bengali)

Kavitabhavan

364/19 Netaji Subhasacandra Basu Road.

Calcutta 47

Sept. 4, 1973

Dear Clint,

I've been awfully late in sending you a copy of Ashoke Mitra's review and I hope I haven't held up the progress of your dissertation. But here it is at last, copied out neatly by Swati, and checked by me.

As you know, Bengali fiction-writers are kept busy during July and August, meeting the demands of various Puja Specials. This year I wrote unwillingly, painfully--my mind is off fiction at the moments being absorbed in the Mahabharata and related classics.

Hind Pocket Books isn't going to send any proofs to either you or me, they say they have excellent proof-readers. I didn't insist, having much to do on my own, and hoping for the best. Mr. Malhotra has requested material for the blurb (which I have asked Jyoti to write)--I expect the book is in the press or soon will be. *(Perhaps it would be correct to state in the blurb or title page that the book was translated with the help of the author. Or do you prefer some other phrase?)

So the chances of a hard-back American edition are pretty slender! I'm glad, though, that James Laughlin and Leila have read the novel and have good things to say about it. Are you in touch with Ruta Pempe? She wrote me 2/3 months ago saying she was sending me some paper she had read at the Bengali conference, but nothing has arrived as of date.

You ask about a new edition of RBB. Yes, Supriya Sarkar re-issued it in paperback (Rs.3/- only!) shortly after the High Court judgement was delivered, I expect it is doing well. Another Delhi publisher is bringing out the Hindi version, done by Bharat Bhushan Agarwal, who I understand is a noted Hindi writer.

I didn't know about the lightening of US obscenity laws until you sent me the clipping. I have passed on the stuff to Jyoti who intends to write on Obscenity (in general) in his Kolkata. The family is well and hale, but Mrs. B. isn't up on her feet as yet. The fracture has healed and she has resumed her massage and electric treatment; also, slowly, taking steps with calibres on. But for this failing, her general health is good and she keeps up her spirits marvellously.

The family sends you love and warmest wishes to all Chicago friends.

As ever,

(sd.) Buddhadeva

Ashoke Mitra, himself a poet, had reviewed Jibanananda's book Satti tarar timir ("Darkness of Seven Stars") in Kavita. I had neglected to copy out the entire review, and it was not contained in the issues of Kavita that I had brought back to sell to the University of Chicago library. Consequently, I had requested from Buddhadeva a copy of the review, which I needed for my dissertation on Jibanananda. He got his daughter-in-law, Pappa's wife Swati, to handcopy it for me.

Mahabharater katha did not appear in book form until 1974. As Sujit Mukherjee tells us in the preface to his translation of that work, Buddhadeva "had planned a companion volume to the original work, but passed away even while the last pages of the first volume were being printed." The Book of Yudhisthir, p. xii.

Buddhadeva's suggestion, that the blurb or title page reflect the fact that the author had helped with the translation, was a good one. In the published book, there is no statement to that effect, which is unfortunate.

The High Court had reversed the ruling of the lower court and exonerated Buddhadeva and the novel. Supriya Sarkar of the publishing house of M. C. Sarkar, who first published the book in 1967 and priced it at Rs.5/-, reissued it in paperback for Rs.3/-, astounding Buddhadeva. (The work had been written the year before that, 1966, for the Puja issue of the magazine Jalsa; Buddhadeva tells us in a brief statement in the front material that the novel included much new material.)

Kolkata was a literary magazine Jyoti founded and edited.

Letter #18

Calcutta 47

October 16, 1973

My dear Clint,

Just now I looked for my copy of Banalata Sen, but could not find either the Kavitabhavan or the Signet edition, so I'm answering your queries trusting hopefully in my memory. At any rate the ones you cite definitely are prose poems (I'm glad you have developed an ear for Bengali verse); if there are any others in the Sig. ed. I'll let you know when I have looked at the book. The beginning of the Bengali prose-poem, in my view, is in the first 14 pieces in Lipika (1922). I think I have said so in writing and R.T. [Rabindranath Tagore] himself acknowledged as much in the preface to Punashcha. Now several of these Lipika pieces are re-workings of some juvenile prose passages; if you feel like going into it you can find out details by writing to Naresh who has gone into this minutely. The form was certainly developed by the poets of my generation (see my reviews and essays passim); I think the influence of D.H. Lawrence and Pound was also there (also that of Whitman in Premendra Mitra's juvenilia). So far the picture is clear, but you are not right in assuming that Tagore tried to restrain the prose-poem and even "hoped it might disappear"; this is far from the truth. *(Also note R.T.'s volumes of prose-poems published after Punashcha and his many essays justifying the form.) On the contrary, R.T. took another step in writing payar-based metrical poems in perfect prose syntax and vocabulary (see Parishesh 1st edn. or new edn., Punashcha)--good examples are "kinu goaalar gali" ["bansi"] and "upare jabar sinri" ["unnati"]--contiguous are a few more). For some reason, this form was not taken over by the younger poets; I once essayed it in a long poem called "Bideshini"--and that's about all.

I have written down whatever came to my mind at the moment--perhaps more than what you need--but if you have any other questions I will try to help you.

As you know by now, Ed did get to Calcutta and saw us for a few minutes despite his being terribly rushed and the distance of Naktala. He looked more browned than ever and more handsome now that his beard is turning grey. He said he would be here again in December for a longer stay--we hope this works out.

I haven't heard recently from Hind and have no idea when the book will be issued. I guess everything is going slow because of power shortage everywhere in India. In Calcutta life is becoming increasingly more difficult, but we hope to survive. It would have been easier for me only if Mrs. B. were up on her feet again.

Love from all,

as ever,

(sd.) Buddhadeva