-

পরবাস

বাংলা ভাষা, সাহিত্য ও সংস্কৃতি

Parabaas, a Bengali webzine since 1997 ... ISSN 1563-8685 -

ছোটদের পরবাস

Satyajit Ray

Rabindranath Tagore

Buddhadeva Bose

Jibanananda Das

Shakti Chattopadhyay

সাক্ষাৎকার -

English

Written in English

Book Reviews

Memoirs

Essays

Translated into English

Stories

Poems

Essays

Memoirs

Novels

Plays

প্রিয় করস্পর্শ

শক্তি চট্টোপাধ্যায়-

পুত্রবধূর কলমে গৌরী আইয়ুব এবং প্রসঙ্গত

-

বিশ্বের ইতিহাসে হুগলি নদী

-

বেদখল ও অন্যান্য গল্প

-

Audiobook

Looking For An Address

Nabaneeta Dev Sen

Available on Amazon, Spotify, Google Play, Apple Books and other platforms.

-

পরবাস গল্প সংকলন-

নির্বাচন ও সম্পাদনা:

সিদ্ধার্থ মুখোপাধ্যায়)

-

Parabaas : পরবাস : বাংলা ভাষা, সাহিত্য ও সংস্কৃতি -

পরবাস | Shakti Chattopadhyay | Memoir

Share -

Thirty-Eight Years with Shakti : Samir Sengupta

translated from Bengali to English by Bhaswati Ghosh

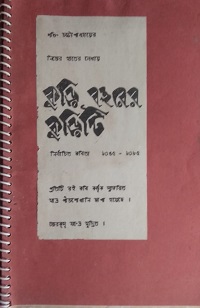

From Shakti Chattopadhyay's handwritten facsimili edition of

Kuri Bochhorer Kuriti

('Twenty Years, Twenty Poems')

I first met Shakti in 1957, at the College Street Coffee House. I still carried on me the smell of Ramakrishna Mission’s Vidyamandir from where I had just graduated. The modernity of Coffee House startled me almost every day. I would find myself a corner to sit at the Krittibas table, with the poets barely tolerating me. Scores of foreign names—of poets, novelists, films, filmmakers—rained down my head. Every single day, I would hear new names—how in the world could I get to read so many books, watch so many films? I hadn’t even seen the magazine Kabita (*Poetry, কবিতা ) yet. I have faint memories of Shakti wearing a red tie and commuting to his workplace, Hind Motors as a daily passenger.Somehow, with time we became friends. I didn’t write any poetry, only dealt with prose, that too very little. I had enrolled into Jadavpur University’s master’s program in Comparative Literature, which brought me an entry into the haloed and unique adda of ‘Kabita Bhavan’ (*lit. house of poetry, residence of Buddhadeva Bose, founder-editor of Kabita). Shakti’s name was still on the student roll, but one hardly saw him on the campus. He would (suddenly) show up once every six or nine months and that would be it. He was part of the batch following ours, a classmate of Rumi’s (Damayanti Basu Singh, Buddhadeva Bose’s youngest daughter) in the BA course. Buddhadeva had forced him to enroll with hopes of making him return to the mainstream. By then, however, a witch had already seized Shakti’s heart.

Shakti didn’t present me the first edition of Hey Prem, Hey Noisshabdo ('O Love, O Silence', হে প্রেম, হে নৈঃশব্দ). I received the book a month after its publication, when Anil Sinha of the Natun Sahitya magazine gave it to me along with half a dozen other books for reviewing. The first book I received as a gift from Shakti was

Rupkathar Kolkata ('The Kolkata of Fairy Tales', রূপকথার কলকাতা)—inscribed with his small, rounded signature of the time—To Samir from Shakti, August 12, ’65 (Rupchand Pokkhi ['The bird Rupchand']). Thereafter, I received almost all his books as gifts. After I got married,

Rupkathar Kolkata ('The Kolkata of Fairy Tales', রূপকথার কলকাতা)—inscribed with his small, rounded signature of the time—To Samir from Shakti, August 12, ’65 (Rupchand Pokkhi ['The bird Rupchand']). Thereafter, I received almost all his books as gifts. After I got married,  he autographed them with “To Maya and Samir,” without exception. Occasionally, he gave me two copies of the same book, as I would discover while organizing my books later. I received Manush Bawro Kaandchhe ('Humankind Weeps', মানুষ বড়ো কাঁদছে) dated October 8, 1978 once right after its publication; and another copy with the words, “To Maya and Samir, from Shakti”, dated May 6, 1985. In Collected Poetry 2, he signed with blue ink “To Maya and Samir from Shakti, April 4, 1993;” below which, in red ink he wrote, “Wishing Maya a quick recovery.” At the time, Maya was suffering from a daily low-grade fever that no treatment seemed to help. The last book I received from Shakti was Jangal Bishaade Achhe ('The Forest lives in Sorrow', জঙ্গল বিষাদে আছে) with a date of March 3, 1994.

he autographed them with “To Maya and Samir,” without exception. Occasionally, he gave me two copies of the same book, as I would discover while organizing my books later. I received Manush Bawro Kaandchhe ('Humankind Weeps', মানুষ বড়ো কাঁদছে) dated October 8, 1978 once right after its publication; and another copy with the words, “To Maya and Samir, from Shakti”, dated May 6, 1985. In Collected Poetry 2, he signed with blue ink “To Maya and Samir from Shakti, April 4, 1993;” below which, in red ink he wrote, “Wishing Maya a quick recovery.” At the time, Maya was suffering from a daily low-grade fever that no treatment seemed to help. The last book I received from Shakti was Jangal Bishaade Achhe ('The Forest lives in Sorrow', জঙ্গল বিষাদে আছে) with a date of March 3, 1994. While he was alive, I didn’t buy any of Shakti’s books. The first one I bought was The Poetry of Khalil Gibran (translated by Shakti and Mukul Guha), in April last year (1995). I got two copies—one for myself, one for Minakshi (Shakti’s wife). They too didn’t have a copy in their house.

There were quite a few books by Shakti that I hadn’t even come across in his lifetime. He seldom mentioned when a new book came out, unless I accidentally saw it in his hands or his house. For someone who had a book coming out once every quarter (that would be four in a year), it was probably not even feasible to let folks know. After his death, an exhibition of all his books was held at the Bangiya Sahitya Parishad, mainly on the initiative of Sankha Ghosh. His former students, Tarapada Acharya and Avik Majumdar were spearheading the effort, and I was also part of it. During this time, a book called Purono Sniri ('The Old Staircase', পুরনো সিঁড়ি) was discovered from the very library of the Parishad. The book, with no publication date included, was probably printed in 1967. The publisher, Debkumar Basu (who had published Shakti’s first book at his own expense) was closely associated with the Parishad and had possibly donated the copy to the library.

That was also when I saw the first edition of Chaturdashpadi Kabitabali ('Collected Sonnets', চতুর্দশপদী কবিতাবলি) for the first time. The copy belonged to Bhaskar Chakraborty (poet). Despite my repeated pleadings, Bhaskar refused to part with the book, forcing me to get it photocopied. I discovered yet another strange book at this time—Ekhon Rakhal Banipriyar Jonno Saswata Sweekarokti ('Now Cowherd For Banipriya Eternal Confession', এখন রাখাল বাণীপ্রিয়র জন্য শাশ্বত স্বীকারোক্তি)—the quirky title was good enough to throw anyone off. When flipping the pages, I found it to be a joint collection of four poets. Shakti’s portion is called 'Now' and Sunil Gangopadhyay’s 'Cowherd'. The two other poets were Shyamal Purakayastha, whose portion was called 'For Banipriya' and Abhijit Ghosh, whose portion was titled 'Eternal Confession'. The book had Ajit Dutta’s name as the editor. It also carried an introduction by Ajit Dutta where he severely criticized the poets. I have yet to come across a stranger book.

That was also when I saw the first edition of Chaturdashpadi Kabitabali ('Collected Sonnets', চতুর্দশপদী কবিতাবলি) for the first time. The copy belonged to Bhaskar Chakraborty (poet). Despite my repeated pleadings, Bhaskar refused to part with the book, forcing me to get it photocopied. I discovered yet another strange book at this time—Ekhon Rakhal Banipriyar Jonno Saswata Sweekarokti ('Now Cowherd For Banipriya Eternal Confession', এখন রাখাল বাণীপ্রিয়র জন্য শাশ্বত স্বীকারোক্তি)—the quirky title was good enough to throw anyone off. When flipping the pages, I found it to be a joint collection of four poets. Shakti’s portion is called 'Now' and Sunil Gangopadhyay’s 'Cowherd'. The two other poets were Shyamal Purakayastha, whose portion was called 'For Banipriya' and Abhijit Ghosh, whose portion was titled 'Eternal Confession'. The book had Ajit Dutta’s name as the editor. It also carried an introduction by Ajit Dutta where he severely criticized the poets. I have yet to come across a stranger book. The exhibition was also where I first saw Shakti’s novel titled Lucy Armanir Hridoyrahasya ('The Secret at the Heart of Lucy Armani', লুসি আর্মানীর হৃদয়রহস্য), written under the pseudonym of Rupchand Pokkhi ('The bird Rupchand'). The dedication page of the book has these words—“Dedicated to the vociferous Minakshi Biswas whose words helped me find the lost manuscript of this novel.”

Had I not known Shakti, I would have found it hard to believe that an author could be so brutally detached from his published books. I had been trying to create Shakti’s bibliography since 1989, when I began working on editing Agranthita Shakti Chattopadhyay ('Unpublished Shakti Chattopadhyay', অগ্রন্থিত শক্তি চট্টোপাধ্যায়) based on his old manuscripts. We needed to go through all his books to determine if a particular piece of writing was indeed unpublished. But Shakti had no interest in this venture. The collection at his house was anything but reliable. Many of his own books he never even brought home. Of whatever he did bring, he gave many away to anyone who asked for them. To Minakshi’s objections, he would simply say, “I’ll bring another copy, don’t worry,” a promise he never got around to keeping. Filled with torn, dog-eared titles, with other books spread in between, the shelves of Shakti’s books in his own house looked like they could belong to a failed Class 7 student. Despite Minakshi’s best efforts, the shelves never attained any grace, thanks mainly to Shakti’s crude touch. Anyhow, using that very collection along with my own books, Debu-da’s (Debkumar Basu) collection and those of a few other friends, I managed to put a bibliography. Shakti was delighted and said, “Bah, this is fantastic, Samir. I didn’t even remember this book...no, I’m certain this covers everything.” A few days later when yet another book was discovered, Shakti would say with an awkward smile, “Oh, yes, yes, that one had come out, too...”

Yet, Shakti’s sharp memory in other areas of his life often surprised people. In particular, his ability to remember people’s names and faces was astonishing. A couple of years before his death (1995), we visited Santiniketan during the Basantotsav (spring festival). After the morning’s program at Gour Prangan, we all sat huddled together in Amra Kunja (mango grove), where a woman came, touched Shakti’s feet and asked, “Do you remember me, Shakti-da?”

Shakti welcomed her as though he had been waiting for her all this while. “Here you are, Neela! How wonderful; we’ll have a great time now.”

The woman was taken aback. “You remember my name?”

“Why wouldn’t I? Wasn’t it just in 1974 that I spent three days in the room next to yours at Beachview Hotel in Gopalpur? We had so much fun; how can I forget your name? How is Subrata doing and what are Tutul and Putul up to these days?”

For someone who didn’t take a minute to recollect the name of the woman—and her husband and children--with whom he’d spent barely a few days in a hotel twenty years ago, it was nothing to forget the names of his landmark books just like that.

Maya and I had gone to Shakti’s house one evening to formally invite them to our wedding. They weren’t home. I had written the reason for our visit on a scrap of paper and slid that under their door. Twenty-two years later when I was compiling the Unpublished Shakti volume, that letter surfaced as we rummaged through the manuscripts Minakshi had saved over the years. On the reverse side of that scrap were the drafts of two poems, one of which became famous later,

উদ্ভিদের মত কৃতী, তবু তাকে বর্জন করেছি

I have rejected him, despite his flourishing growth, plant-likeBoth the poems were dated August 2nd. They were probably written at the same time; one had corrections scribbled through it while the other one was spotless. My letter on the reverse side was dated June 9, 1968, so it’s safe to assume that Shakti’s poems were written on August 2 of the same year. The poem(s) had appeared in the Ashiwn 1375 (Bengali year) of Alindo ('Balcony', অলিন্দ), which corresponded to September-October 1968.

Those days were a struggle for them. Fed up with mistreatment from the school authorities, Minakshi had quit her job at South Point. Shakti’s livelihood amounted to subsisting on the odd literary, journalistic and publishing pursuit, such as writing a column called 'Weekend Tourist Guide' in Anandabazar Patrika. Almost overnight, he crafted a lousy novel titled High Society, brought out by Mandal Book House. Another publication started bringing out Sreshtha Kabita ('Best Poems', শ্রেষ্ঠ কবিতা) series, Shakti’s brainchild. This was a new trend in Bengali. Let it be documented here that the Best Poems genre that the Bengali poetry world is so crazy about today was Shakti’s idea; he was the first one to realize its tremendous potential. At the same time he was translating the Rubáiyát of Omar Khayyám and marking a shift in his own poetry.This became evident when Hemanter Aranye Ami Postman ('I Am a Postman in the Autumn Woods', হেমন্তের অরণ্যে আমি পোস্টম্যান) came out in March 1969. This was also when he wrote,

Those days were a struggle for them. Fed up with mistreatment from the school authorities, Minakshi had quit her job at South Point. Shakti’s livelihood amounted to subsisting on the odd literary, journalistic and publishing pursuit, such as writing a column called 'Weekend Tourist Guide' in Anandabazar Patrika. Almost overnight, he crafted a lousy novel titled High Society, brought out by Mandal Book House. Another publication started bringing out Sreshtha Kabita ('Best Poems', শ্রেষ্ঠ কবিতা) series, Shakti’s brainchild. This was a new trend in Bengali. Let it be documented here that the Best Poems genre that the Bengali poetry world is so crazy about today was Shakti’s idea; he was the first one to realize its tremendous potential. At the same time he was translating the Rubáiyát of Omar Khayyám and marking a shift in his own poetry.This became evident when Hemanter Aranye Ami Postman ('I Am a Postman in the Autumn Woods', হেমন্তের অরণ্যে আমি পোস্টম্যান) came out in March 1969. This was also when he wrote,

যায় যায় বললেও সবটা যায় না,

কিছু থাকেই—যার নাম জীবন

Not everything is lost even when one insists it is so

Something invariably stays—and that is life

How many poems did Shakti write? The number of poems in the books published during his lifetime amounts to 2,175. When I mentioned that to him one day, Shakti was shocked. “Are you serious? Only twenty-one hundred poems? From ’61 to ’71, I wrote at least three to four poems a day—for an entire decade.” Even if that was inaccurate, and it probably was, if he had written even an average of one poem a day during that time, this prolific decade alone must have produced at least 3,000-3,500 poems, a number much higher than his published poems over the 40-year period of his poetic life. He wrote for anyone who asked him to; goaded by the witch in his heart, the verses melted off the tip of his forefinger. He didn’t keep a copy, didn’t collect cuttings, didn’t tell Minakshi, failed to remember himself, didn’t bring home a journal even if someone gave it to him. An extraordinary assignment awaits a dedicated and meticulous poetry researcher—to collate all of Shakti’s unpublished poems by digging into old issues of little magazines.Ahead of the 1979 Boimela (Kolkata Book Fair), I decided to do something different and exciting to celebrate Shakti’s work. What could we do? As I deliberated on it, I thought of bringing out a collection of Shakti’s poems in his own handwriting. Xerox offset publishing had just come to Calcutta and was yet to catch on. Luckily, I knew a fair bit about the process. Shakti had 18 collections of poetry at that time. I decided to pick one poem each from all of them, plus two of my favourites from his 14-Line Poems' ('Sonnet Collection', চতুর্দশপদী কবিতা) and one unpublished poem to bring out a collection titled Kuri Bochhorer Kuriti ('Twenty Years, Twenty Poems', কুড়ি বছরের কুড়িটি). I made my selection. But the real problem lay elsewhere—getting Shakti to handwrite these 20 poems.

Shakti refused right away. Copying 20 poems by hand? No way, he said. Had Minakshi not supported me back then, the entire project would have been scrapped. He only agreed, reluctantly, with Minakshi’s scolding.

But what use was his agreement? A year and a half before this initiative, Shakti and Minakshi had moved to Colonel Biswas Road. I would go and wait at his house every evening. On most days Shakti returned home very late and in a state that didn’t leave him good for anything much. Whenever he was in a functional state, someone or the other would drop by. In between there would be some days when he would copy four or five poems at a stretch. To ensure the printing was of high quality, I had left expensive, good-stock paper at Shakti’s house. He loved the paper so much that he exhausted all of it to write new poems. I had to buy him more paper.

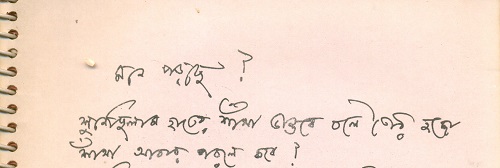

That is how, one day, the task of getting all the 20 poems copied in his handwriting was completed. The book fair had already started by then. Those who have seen Shakti’s manuscripts would know how neat and scratch-free his writing was, as if he could see every word he had to write in front of his eyes. He hated revising his work. This is what he wrote in the introduction to Sonar Machhi Khun Korechhi ('I Have Killed the Golden Fly', সোনার মাছি খুন করেছি), “As far as possible, I don’t like making corrections—I like to be worry-free by imprinting on the page the exact images and musical lines as they appear.” Because of this, the poems he copied all looked like his original manuscripts, save a few scratches here and there, which I actually wanted, in favour of keeping it real. What beautiful handwriting Shakti had! Some of his letters had Rabindranath’s roundness, others Vidyasagar’s straight strokes—but every letter was clean, never mixed up with any other. As they all came together, the lettering acquired a cast graceful enough to make even a seasoned calligraphist envious. I’ve remained familiar with Shakti’s manuscripts for 40 years, and in my observation his basic handwriting never changed, except for a few years in the middle when his writing became so tiny that one needed a magnifying glass to read it.

The manuscript was thus prepared, and even printed without any hassle. Prithwish (Prithwish Gangopadhyay, artist) had promised to do the cover, but—as usual—was unavailable just when needed. I was thus forced to do the honours at the last minute. The book was ready and everyone heaved a sigh of relief—it wasn’t altogether a bad product. For books such as these, appearance was a key aspect. We went for a red cartridge cover and a spiral binding. It was supposed to look too attractive to be resisted by the readers. But the book fair was nearing its end.

The manuscript was thus prepared, and even printed without any hassle. Prithwish (Prithwish Gangopadhyay, artist) had promised to do the cover, but—as usual—was unavailable just when needed. I was thus forced to do the honours at the last minute. The book was ready and everyone heaved a sigh of relief—it wasn’t altogether a bad product. For books such as these, appearance was a key aspect. We went for a red cartridge cover and a spiral binding. It was supposed to look too attractive to be resisted by the readers. But the book fair was nearing its end. We were still left with the main task—because without informing Shakti, I had printed this on the cover—“Every copy is signed by the author.” We had printed only 500 copies.

With a palpitating heart, I took 500 books to Shakti’s house to have him sign them.

Shakti was so elated on seeing the edition that we were spared his potential wrath. He just chuckled and said, “So I have to sign five-hundred books? Oh dear, that’s like imminent death. OK, give me a pen. I’ll start right now—the book fair is about to end anyway.”

The books reached the fairgrounds three days before the end of the book fair. I had left 10 copies at the stall of Debkumar Basu of Darshak ('Observer', দর্শক) magazine and 10 more at the Subarnarekha stall. The rest were sold from the Krittibas stall in one day. Kalyan Majumdar gathered crowds to the stall by standing atop a table in front of the stall and yelling to the crowd like they did in circus tents at village fairs. People would pick up the book mainly because of his hollering, but once they had it in their hands, they wouldn’t be able to put it back. The books were sold with great fanfare all through the afternoon and evening. When the end of the book fair was announced on the microphone, only one copy was left in stock.

That was when the inimitable Sandipan Chattopadhyay (littérateur, belonged to Krittibas group) launched into action. How? By yelling to the crowd, “The last copy of this year’s most astonishing book is now auctioning.” Within minutes, people thronged the stall, surrounding the tall and lanky Sandipan standing on the table. The price of the book kept going up by a rupee or two. The 5-rupee book was sold at 32 rupees in the end.

That was when the inimitable Sandipan Chattopadhyay (littérateur, belonged to Krittibas group) launched into action. How? By yelling to the crowd, “The last copy of this year’s most astonishing book is now auctioning.” Within minutes, people thronged the stall, surrounding the tall and lanky Sandipan standing on the table. The price of the book kept going up by a rupee or two. The 5-rupee book was sold at 32 rupees in the end. From the profits, Maya gave some gifts to Minakshi and Shakti’s children, Babui and Tatar. Shakti didn’t get anything.

The unpublished poem in that edition, 'Monay Porchhe?' ('Do you remember now?', মনে পড়ছে?) was later included in Manush Bawro Kaandchhe ('Humankind Weeps', মানুষ বড়ো কাঁদছে).

On one occasion, Desh magazine had asked Shakti to write a prose piece for their Durga Puja special edition. He couldn’t get a grip on the piece. As someone who could write memorable poetry effortlessly, he had to struggle to craft a piece of prose. One day he said to me, “Samir, let’s go to Haldia for a few days. A riverfront bungalow is available there. Maybe that will help me finish this piece?” I readily agreed, working as I was on translating Shakti’s poems into English at the time.

We spent an amazing week in Haldia. We had a huge bungalow, the property of a foreign company for the luxury of its Indian officers, to ourselves. We slept on two adjacent beds in the same room. They had offered us two separate rooms, but Shakti refused to stay alone for his fear of ghosts. Early in the morning, he would sit at the table with his writing—he would write and scratch, write and tear the pages, write and discard the writing. At times, he would sit quietly. For the entire day, he would be at the table. Crystal bottles of alcohol seductively stood before him like slave girls, waiting for a single beckoning. Shakti wouldn’t look at them before the evening, and even then, he drank little more than two glasses of chilled beer. I saw Shakti struggling only that one time—with language, with himself, with prose. As a writer, Shakti depended on inspiration, be it for poetry or prose. For this reason, it was difficult for him to write prose on demand. Such writings of his were mostly forgettable. I don’t remember what Shakti wrote during our vacation in Haldia or if he even managed to write anything. I only remember his struggle—his superhuman fight, using unfamiliar weapons, against an unequal opponent.

When it came to poetry, Shakti could think with lightning speed, so fast that the idea itself would be hard to grasp. For this reason, a few seasoned critics have described Shakti as a natural, instinctive poet at heart. One could argue that this is true of all poets. But this tag is particularly achieved by writers who are content with solely penning down inspiration as it strikes, who don’t have to add effort to that inspiration. Some poets wear the imprints of their efforts with pride. Poets like Alokeranjan Dasgupta and Sankha Ghosh come to mind. Then there are others who keep all their efforts hidden, what they present to their readers gleam like perfect pearls without any stains of teardrops—poets like Subhash Mukhopadhyay, like Shakti. Sometime ago, in an article in The Statesman, Utpal (Utpal Kumar Basu) had described Shakti as “spontaneous” and “fastidious” at once. The way these two mutually contradictory adjectives suit Shakti would be an exception for most poets. Being a poet himself, Utpal realized the precise investment Shakti made. Behind his apparent spontaneity, Shakti was acutely alert to his hypersensitive perceptions, on the weight and the subliminal import of every word.

Shakti spoke little, almost nothing, about poetry. I have yet to meet someone who has had a lengthy discussion on poetry with Shakti. Occasional comments that slipped off his tongue hinted at his complete immersion in the poetic world. For instance, while listening to a Rabindrasangeet (songs by Rabindranath Tagore) one day, he remarked, “Oh, I could never use that word 'Nichhoni' (physical embellishment or a gift/offering, নিছনি)!” Another time, I couldn’t decipher a word in one of his older manuscripts and asked, “What is this, Shakti, 'gobheer' (deep, গভীর) or 'gombheer' (solemn/grave, গম্ভীর)?” Without even looking at the text, Shakti said, “It can’t be 'gombheer'. I don’t think I’ve ever used that word.” As I thought about and even searched for it later, I actually couldn’t find that word in any of his writing. That might not be a big deal, but it was amazing to me that having written thousands of pages, he could remember that he had never used a word as ordinary as Gombheer. It takes some degree of consciousness and attention to keep that in mind.

And, Shakti had another outstanding ability—the ability to receive love. I call this an ability and not fate because such instances abounded in Shakti’s life. If such incidents occur only occasionally in a person’s life, they can be called strokes of luck. But when they continue to happen over and over and become almost a rule, this phenomenon can’t be attributed to a person’s good fortune but must be seen as a special ability they possess. I saw it myself how, after getting off a taxi at midnight, when Shakti fell short of four rupees for the fare (this was in the 1970s, when that was a decent sum), he held the driver’s cheeks and said, “I don’t have any more dear; be happy today with what I have?” The Bengali taxi driver simply touched Shakti’s feet—yes, actually touched his feet and left without a word.

We had a Bihari friend who had gained some fame as a Hindi poet. He used to be Shakti’s close pal at one time. In the mid-1950s, he worked in a nationalized bank and lived in a rented house in Kalighat. Shakti would often land up in his house in the middle of the night and wake up his family, hollering at his wife, “Hey Lachhmi, I am hungry, give me a couple of rotis to eat.” This became such a routine that Lachhmi began saving two rotis and some vegetables every night, in case her Shakti-da appeared unbidden. Shakti showed up often enough for Lachhmi’s saved food to come into good use.

After a while, our poet friend got transferred to somewhere like Dhanbad or Patna. Lachhmi continued living in Calcutta for their children’s education. Shakti’s visits to their house became infrequent. He would still go there every once in a while and eat Lachhmi’s roti and tarkari. This became a ritual for Lachhmi. She saved food for Shakti every night, which she gave away to beggars in the morning. It so happened that once her husband arrived from Dhanbad in the middle of the night without informing her. Lachhmi got up drowsily to make his dinner. Our friend said to her, “Why bother cooking? You can give me the food you’ve kept for Shakti-da. He isn’t going to come so late in the night. He hardly does anyway these days.” Lachhmi shook her head with a smile and said—“That is for Shakti-da and can’t be served to anyone else. Not even to you. I will make fresh food for you.” Lachhmi went on keeping the two rotis and vegetable curry for her Shakti-da, most of which she would have to give away to a beggar in the morning, not just for a few days but for twelve years. What had this semi-literate woman seen in her Shakti-da? What had the taxi driver seen in his passenger of mere half an hour?

Shakti and Minakshi Chattopadhyay (right)

with Maya and Samir Sengupta (left)

Ghesadi, 1968 (from Amar Bandhu Shakti)

For a video film Bishnu Palchowdhury was shooting on Shakti, we went to Jhargram as a group. It was early morning, and we had come to the forests and hills far from the city for some outdoor shots. On our way back, at around 11 in the morning, we saw around fifteen Adivasi (tribal) men and women at a country liquor shack. Bishnu said, “Shakti-da, let’s get some shots of yours with them. Why don’t you go and strike up a conversation while I set up the camera?” Shakti readily went over to join the Adivasi group. It took us half an hour to set up the equipment, ten minutes to shoot and about fifteen minutes to pack up—no more than three quarters of an hour. We were ready to move on when we realized the group of men and women wouldn’t let go of Shakti. “Let those Babus go, you come with us to our village,” they said to him in Santhali. It took a great deal of convincing from Shakti—he took the directions to their village and promised to return soon—to be allowed to take their leave. What had they seen in a pant-shirt wearing, dark complexioned man from the Babu community? This is a community they hold with suspicion and fear, a community they usually stay away from. In fact, they are so embittered with the genteel city folks that Adivasi mothers scare their children with the threat of “Dikus” or Babus coming to get them to make them fall asleep.Those Adivasis, that taxi driver, Lachhmi—none of them have read modern Bengali poetry, have they?

I knew another taxi driver—as did many people—easily recognizable if I revealed his name. A lean, handsome Punjabi young man who wrote poetry in Gurmukhi, he was also a great admirer of Shakti. When Shakti won the Sahitya Akademy award, his full-page portrait had appeared on the cover of Illustrated Weekly of India. Our taxi driver friend plastered this photo on the back of his cab that he took around the town. “Our Shakti-da has won an award!” Shakti loved Kuldip. At one point, Kuldip was a regular presence during breakfast at Shakti’s Park Circus house. At an event when the organizers arranged for Kuldip to read his poems alongside Ayan Rashid Khan (co-translated with Shakti poems of Mirza Ghalib), Rashid was livid. Later, when Kuldip wanted to buy a taxi, he didn’t have the base amount for it and approached Shakti for help. Shakti went to the bank with him, signing up not only as his guarantor but also paying for his collateral security by mortgaging his own insurance policy of 50,000 rupees. Once the taxi was bought, there was, expectedly, no trace of the young man anymore. He had probably escaped to Drugh or Asansol with his vehicle. Shakti continued to pay the premiums on the mortgaged policy year after year with the conviction that his friend would return to pay off the debt and recover the insurance policy. That never happened.

I’ve been Shakti’s friend for a long time and we’ve been witness to each other’s joys and pains. I have cleaned up an unconscious Shakti, dressed him in my own clothes and made him lie down on my own bed. Shakti had washed my pajamas and undergarments on our trips together. Yet, I never really got to know him well. The sphere of our lives intersected the other’s orbit only by a small fraction. I’m a mere mortal who bides his time by storing in his shirt’s pocket dry petals that fall at Saraswati’s feet. How would I recognize someone whose lips have been bruised and battered by kisses churned off the goddess of learning?

Aloke Sarkar (poet) had apparently seen Jibanananda Das drawing buckets of water from a roadside tap. I, too, have seen a bit of Shakti, the everyday man. Shakti, the poet has forever remained elusive to me—hidden behind the curtain of his creation.

My sincere thanks to Chhanda Chattopadhyay Bewtra, whose keen peer review helped polish this translation.

The original article titled "Shaktir songe aTtrish bachhor" (শক্তির অঙ্গে আটত্রিশ বছর) was first published in Sharadiya Basumati, 1996 (BE 1402). It has been later collected in Amar Bondhu Shakti (আমার বন্ধু শক্তি) by Samir Sengupta; published by Parampara, Kolkata in 2011.

Parabaas, November 2020 - এই লেখাটি পুরোনো ফরম্যাটে দেখুন

- মন্তব্য জমা দিন / Make a comment

- মন্তব্য পড়ুন / Read comments

- কীভাবে লেখা পাঠাবেন তা জানতে এখানে ক্লিক করুন | "পরবাস"-এ প্রকাশিত রচনার দায়িত্ব সংশ্লিষ্ট রচনাকারের/রচনাকারদের। "পরবাস"-এ বেরোনো কোনো লেখার মধ্যে দিয়ে যে মত প্রকাশ করা হয়েছে তা লেখকের/লেখকদের নিজস্ব। তজ্জনিত কোন ক্ষয়ক্ষতির জন্য "পরবাস"-এর প্রকাশক ও সম্পাদকরা দায়ী নন। | Email: parabaas@parabaas.com | Sign up for Parabaas updates | © 1997-2025 Parabaas Inc. All rights reserved. | About Us