-

পরবাস

বাংলা ভাষা, সাহিত্য ও সংস্কৃতি

Parabaas, a Bengali webzine since 1997 ... ISSN 1563-8685 -

ছোটদের পরবাস

Satyajit Ray

Rabindranath Tagore

Buddhadeva Bose

Jibanananda Das

Shakti Chattopadhyay

সাক্ষাৎকার -

English

Written in English

Book Reviews

Memoirs

Essays

Translated into English

Stories

Poems

Essays

Memoirs

Novels

Plays

The Land Where

I Found It All-

পুত্রবধূর কলমে গৌরী আইয়ুব এবং প্রসঙ্গত

-

বিশ্বের ইতিহাসে হুগলি নদী

-

বেদখল ও অন্যান্য গল্প

-

Audiobook

Looking For An Address

Nabaneeta Dev Sen

Available on Amazon, Spotify, Google Play, Apple Books and other platforms.

-

পরবাস গল্প সংকলন-

নির্বাচন ও সম্পাদনা:

সিদ্ধার্থ মুখোপাধ্যায়)

-

Parabaas : পরবাস : বাংলা ভাষা, সাহিত্য ও সংস্কৃতি -

পরবাস | Interview

Share -

Lila Majumdar: A Granddaughter Remembers-- Interview of Srilata Banerjee : Anu Kumar

Lila Majumdar, with son and daughter

Sohini Mitra, Puffin’s commissioning editor, gave me Srilata Banerjee’s email and that was how I got in touch with Lila Majumdar’s granddaughter. Besides getting to know her as the translator of the wonderful Burmese Box (and some news for all Lila Majumdar fans: other translations are in the offing), I found her unbelievably generous and giving with her time. She lives in Calcutta with her family that includes three wonderful children, and despite a packed schedule, she found time to answer the questions I sent her by email. They are so wonderfully detailed and animated that here she is, Srilata (Mona) Banerjee, in her own words about ‘dididbhai’ as she calls Lila Majumdar, her writings and her lasting legacy to us.

AK: Tell us when you first became aware that your grandmother was Lila Majumdar?

SB: I don’t know about becoming ‘aware’ that she was a well-known writer. I suppose it gradually seeped into our psyche that there were people outside the family who knew her and seemed to like her very much. When we went out for a walk or something, total strangers would walk up to us and do ‘namaskaar’ or even ‘pronaam’. Some of them … children as well as adults … had books with them which Didibhai would sign. She would stand talking to them in the friendliest manner, as if she had known them all her life. That was a great quality she had … being able to make friends almost instantly! I remember being somewhat jealous of the time she gave to these people who … to me! … didn’t matter at all.

Then, of course, she would go for ‘meetings’, which I didn’t understand then. Later … years later … I realized they must have been seminars or radio and newspaper/magazine interviews or even award functions. There would be meetings at home, too, and well-known writers like Premendra Mitra etc. would come. We didn’t know they were famous; in fact, Premen-dadu (as we knew him) was our best friend and supporter if we wanted to keep a stray kitten or eat ‘badaamer tokti’ a.k.a ‘chikki’ or things which other grown-ups would never acquiesce to!

In school, too, my Bengali teachers would treat me with a hint of awe that had nothing to do with my being always quite good in the subject (I was a voracious reader and that helped. My school texts were rarely chunks of semi-foreign writings, so to speak, because I had already read most of the stories from which the excerpts were taken! Another legacy … I like to think so … of Didibhai). And more often than not they would call me to the Staff-room on some pretext or other and ask me about my Grandmother or surreptitiously slip a manuscript into my hand and ask me to give it to her. All this accompanied by a nervous giggle! All these things, I suppose, grew into an ‘awareness’ that Didibhai wasn’t really an ordinary person and of course, by the time we were in our teens, we knew just who she was!

With husband, and grandchildren

SB: We saw her very often. At least once a week, in fact, and sometimes even more! Sundays meant spending time in Chowringhee (that is, in their flat in Chowringhee Mansions, where my grandparents lived), starting with breakfast of ‘kochuri-jilipee’ … an institution set by my darling Grandfather! Then I’d spend the better part of the rest of the day reading from the enormous collection of books they had – both my grandparents loved reading! I was a bookworm from infancy and Didibhai encouraged that. What she always protested against was getting hooked to just one type of book (for example, I went through a phase of reading only Enid Blytons) or reading books that were unsuitable for our age. What she always said – and which I fully agree with, although at the time (and especially during my teenage years) I protested violently – was that there was plenty of time for me to read that particular book and I should stick to those that were more suited to my age. ‘You’ll enjoy them more when you understand them entirely,’ she used to say.

My father had a transferable job and there was an entire year which my sister and I spent with Dadu and Didibhai. A good part of my character was shaped during that year, as I realize now. What I mean to say is that a lot of things which are an inherent part of my character developed then perhaps because I saw them in Didibhai and unconsciously allowed my traits to grow.

AK: Tell us about your childhood, finding out about Lila Majumdar and if it was a special childhood because of that.

The Majumdars

For example, she didn’t have any hankering for material things. She was basically very simple in her wants as far as clothes or food went, and she had little or no interest in jewellery or other finery. She was wonderful with the needle and more often than not made her own blouses and embroidered some of them, too. She even made some dresses for my sister and me (though I forget what they looked like just now).

But later on, when I could understand it, I used to feel immensely proud of the fact that so many people knew her and loved and admired her. Some of her fame did rub off on us, her grandchildren, I suppose, but not much. In those days there wasn’t this wild excess of adulation and cult followings and so forth. If a person was famous for something or the other, he or she was greatly admired and respected for his works, but that was all. No-one was really a poster-boy or pin-up girl (except, I suppose, actors and actresses. But I meant on the intellectual front!) There weren’t any Salman Rushdies or J. K. Rowlings then!

AK: Could you tell us a bit about her parents too?

SB: Not much, I’m afraid, as I never saw them. And she didn’t talk much about them, either. Actually Didibhai seemed to have been somewhat wary of her father – though she greatly admired and respected him for his intelligence and upright qualities. And she dearly loved her mother, who seemed to have been the quintessential ‘Ma’.

AK: What was she like as a person – a writer, a mother and a grandmother? Did these many personalities intermingle?

SB: Being a grandchild ... and I was her first one ... there was never any question in my mind as to which persona was uppermost when she was with us. She was Didibhai, a beloved friend. The stories she told us were outstanding – and I’m pretty sure some of them were made up on the spur of the moment and never were printed. There was one about ‘shadow people’ ... those upside-down figures you see on walls when people pass by in the street. There was another about a cow called ‘Neelmoni’ or something like that, who used to wear a necklace.

With great grandchild

AK: Do you know anything about her writing life? Did she have a routine of some kind?

SB: As far as I remember, the mornings were given over to her writing. As soon as Dadu had gone off to his chamber (he was a renowned dentist in his day!) and she had finished her routine of giving out the stores and deciding on the day’s menu (she had some wonderful domestic staff, lucky her!) she would sit down with her writing and carry on till lunch-time. In the evenings she rarely sat down to write because my grandparents had a host of visitors, more often than not. Besides, she loved to sit and chat with her friends and acquaintances – and it wasn’t small-talk or idle gossip. The conversations (and I used to sit behind her chair and listen) ranged through such diverse subjects as politics, the best way to clean marble floors, the possibility of space travel, allopathy versus ayurveda, ancient architecture ... and so on. You get the idea?

AK: Which work/s of her do you like the most?

SB: I like almost all of her books, but I have to say that ‘Goopir Gupto Khata’ (which I have translated) was one of my favourites. Also I love her ghost stories. And I can’t really say why I love these particular stories a degree more than the others – it’s just that I do! They appeal to something within me that I can’t explain.

AK: Her life as a well known and loved writer must have been very different to a writer of similar stature today – I am thinking of Ruskin Bond or even J K Rowling? Did she travel a lot? Did she give readings?

SB: In her time there were no promotional ‘readings’ as such. In fact, that concept is very much a late 20th century phenomenon. Sometimes at a gathering of her ardent fans, she would read out from a newly-published book or short story, or even from an older writing that someone had requested. But there was nothing commercial about it. I think she would have liked the idea of reading to an informed and interested public, but she was always very ‘un-commercial’, if you know what I mean!

People who had read and appreciated her works often came to visit her, just as a mark of respect and to show their admiration. But there was no real ‘fan following’ in the modern sense of the word. Mr. Bond and Ms. Rowling are in a different world and time altogether!

As for travelling, Didibhai did astonishingly little of that. She had never ever been out of her country, although she knew reams about different countries, just by reading about them and then filling in the gaps with her wonderful imagination. And even within the country, she never travelled much. Of course, the first ten or twelve years of her life she spent in Shillong. But barring a few trips to Delhi, mainly for official purposes like award functions and so forth, she was mainly tied to West Bengal. During the war years she spent time in Darjeeling and Kurseong and Madhupur, and later on there was Santiniketan, where she spent several very happy and fruitful years of her life.

AK: Lila Majumdar spent her childhood in Shillong. What was her childhood like? And her memories of Upendra Kishore Ray Chaudhuri and Sukumar Ray?

SB: I know of her childhood only through what she used to tell us, her grandchildren. They were mainly in the nature of bedtime stories or something to calm us down when we were getting too riotous for comfort!

The stories about her childhood were more in the nature of anecdotes. Some of them were hilarious, some touching. She used to tell us about her ‘Jyathamoshai’ ... Upendra Kishore Ray Chaudhuri ... and how he had to eat mainly fruits and boiled stuff because he wasn’t well. It was only when Didibhai’s own sugar level suddenly went up above normal level and she was put on a restricted diet for a while, that she realised he may have had diabetes.

Sukumar Ray died tragically at a very young age of ‘kala-azar’ and Didibhai would tell us how she would go and sit with him when he was confined to bed, and he would show her the drawings for many of the poems in ‘Abol Tabol’. One of the last illustrations he did was for ‘Tyansh Goru’ and Didibhai used to tell us how he laughingly asked her whether another twist in the character’s tail would suit it or not! He died shortly after that.

AK: What was her first story all about, ‘Lakkhi Chele’ – it was also illustrated by her. Did she illustrate all her stories?

SB: No. She could draw and paint beautifully, but she didn’t think much of her own abilities in that field. So she left it to others, whom she thought more competent.

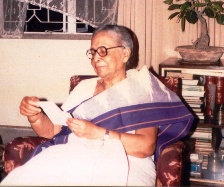

Reading letters

SB: Anu, I’m very sorry to say there has been no such effort by anyone ... not the government, not even the family! Her childhood home in Garpar has some attention given to it – very meagre attention – mainly because it was also the home of Didibhai’s cousin, Sukumar Ray, and also where Satyajit Ray was born. Otherwise, there has been nothing.

Another quite horrific fact ... and please don’t think I’m complaining. Both sides are as much to blame ... is that we (the family) have no first editions of her books, believe it or not! There are several reasons for this. My Mom did have all the copies, but during the terrible flood of 1972, the entire cupboard where the books were kept went under water and her first editions (along with some other very rare and valuable books we had) were totally destroyed. The copies that Didibhai had were ... to put it baldly ... pinched by one of her so-called fans, who used to visit her when no-one was around and walk off with a couple of her books and her paintings each time. The problem is, we have no hard proof that he did it. And though we know the books and things are in his possession, he declares that she actually gifted them to him. So that’s the situation, and there’s little we can do about it, except appeal to anyone who may possess a first edition of any of her books, to let us know about it.

AK: Are these Penguin translations – The Yellow Bird by your mother Kamala Chatterjee and this Burmese Box collection by you – the first proper attempt to ensure Lila Majumdar reaches a wider audience?

SB: Yes, they are. Penguin decided, very kindly, that Lila Majumdar’s works should be appreciated by children all over India and not just in Bengal. So they went ahead with the translations (reviewed here)--- and I hope they will really find a place in the hearts of people all over the country, as they have among so many people in Bengal.

AK: Are there plans for more translations?

SB: I’ve already started on three or four of her books – some of them are almost done! – and I’m only waiting for Sohini’s go-ahead.

AK: The musical drama she wrote, Bok Badh Pala for which she won the award. Could you tell us something about that. Did she compose the music for this too?

SB: No, Didibhai didn’t compose the music. If there was one thing she couldn’t do ... and it was just the one, as far as I remember ... it was sing. She was dreadfully unmusical, although she did enjoy listening to good music occasionally, especially Rabindra Sangeet.

The reason she wrote that play (and also ‘Lanka Dahan Pala’) was because she really loved the wonderful body of stories in our epics and she felt that children should view them as part and parcel of their lives. Especially she wanted to bring out the underlying humour and the human touch in the stories. That was one of the reasons why she wrote the plays.

AK: Do you remember watching this performed?

SB: Unfortunately I wasn’t in Calcutta when the play was produced. So I missed seeing it, although everyone who had, was absolutely ecstatic about it. (I still envy their good fortune!)

AK: Tell us something about Manimala – the character she created for her radio series. I read some translated excerpts of the AIR series that appeared in Telegraph some years ago and am amazed by how much a feminist she appears. So very prescient and aware too – her letters for Manimala makes you think there is really nothing called a generation gap. She seemed a free-thinking, free-spirited sort – what do you think about this?

SB: Anu, I’m combining the two questions, okay? The character of ‘Manimala’ is a great favourite of mine for two reasons – one is that my paternal grandmother’s name was Manimala and both Didibhai and Thamu were very good friends. So when I was very young I was under the impression that Didibhai had written about Thamu. I couldn’t be more wrong!

In actual fact, Manimala was a reflection of Didibhai’s thoughts and feelings at various stages of her life. And that brings me to the other reason why I love the character so much. It reminds me of myself, too. And I like to think that that’s because in character and habits and thoughts I’m very much like Didibhai (my relatives on Ma’s side, including Ma herself, say I’m a carbon copy of her as far as character goes! I wouldn’t go so far, but there are similarities, both good and bad. More anon!).

Didibhai was a true ‘feminist’ – though she hated that term and also ‘Women’s Lib’. She would always say (with a most unladylike snort) that to thrust the concept of freedom forcefully in everyone’s face didn’t necessarily bring freedom. Just because a woman remained at home, cooking and looking after her household and family didn’t mean she wasn’t liberated. In fact, according to Didibhai, such women had enormous power and the ability to mould destinies. I think you’ll find a reflection of that in ‘Manimala’ . Also, she always said that those who shout loudest about the so-called ‘Women’s Lib’ are the ones who don’t follow it to the spirit. For example, once when we were travelling by ‘bus, we noticed an elderly and rather frail gentleman sitting in one of the seats reserved for ladies. He saw us and tried to get up, but Didibhai made him sit down again, saying laughingly that both of us had strong legs and didn’t need to sit. A few minutes later a young and obviously ‘mod’ young thing got on – dressed in the bell-bottoms and knotted blouse that were fashionable in those days – and almost hauled the poor gentleman off the seat with most vituperative remarks. ‘So this is Women’s Lib’!’ was Didibhai’s quiet comment to that ... and it was a lesson I’ve never forgotten. If you want equality, she would say, you must be prepared to accept the difficulties that go with it as well as the good things. It can’t be piecemeal! This thought, too, runs very strongly through her story. She was a true ‘modern’ – and how I wish she could have been here today and in her prime!

AK: She wrote cookbooks too. Do you know the dishes she loved to cook most?

SB: Ha! Didibhai wasn’t really a ‘cook’, in the truest sense of the word, although she did cook as when required. (Her cooks were fantastic!) But she loved food, not just eating but the intricacies of preparing and cooking a dish and how certain spices would go with certain fish or veggies and others would not. She used to say that cooking was like creating a story and she would excitedly collect recipes from everyone because they had a history attached to them.

She loved simple Bengali food and was most disappointed that I didn’t ... although she loved to sample every kind of cuisine and then try and find out how and why they developed as they did. It’s something she’s passed on to me!

AK: Do you have any plans of having her memoirs Aar Khonokhane and Pakdandi translated? I so much wish this.

SB: Ma’s translating ‘Aar Konokhane’ – I think its three-quarters done – and I’ve started on ‘Pakdondi’. You’ll be the first to know if they are going to be printed – I promise, Anu!

AK: There are informal and formal ways in which her legacy is being preserved. As a writer of an earlier age, she wasn’t perhaps very savvy about matters like ‘copyright’. How are you dealing with this?

SB: There are a lot of problems with copyright issues and reprinting of her stories, as well as illegal printing of many of her books. (It’s a problem almost all writers are facing nowadays). My mother and uncle are doing it legally, but it’s a time-consuming and laborious process. Luckily, we do have several well-wishers, especially the Ananda Publishers Group. The Sarkars are family friends and very helpful and kind.

AK: She seems to have been the quintessential Renaissance woman – a writer for children, teacher, playwright, an art critic, etc. How do you think we should remember and honour her?

SB: Please remember her as a happy woman, who wanted to spread joyousness and the spirit of wonder that is found in children. That’s what she wanted, till the last day of her life – the ability that all children have of seeing the world around them as something magical and beautiful, full of light and happiness in which even the inevitable sorrows and ugliness dissolve and are washed away.

Desikottam Lila Majumdar

Published November, 2011

- এই লেখাটি পুরোনো ফরম্যাটে দেখুন

- মন্তব্য জমা দিন / Make a comment

- মন্তব্য পড়ুন / Read comments

- কীভাবে লেখা পাঠাবেন তা জানতে এখানে ক্লিক করুন | "পরবাস"-এ প্রকাশিত রচনার দায়িত্ব সংশ্লিষ্ট রচনাকারের/রচনাকারদের। "পরবাস"-এ বেরোনো কোনো লেখার মধ্যে দিয়ে যে মত প্রকাশ করা হয়েছে তা লেখকের/লেখকদের নিজস্ব। তজ্জনিত কোন ক্ষয়ক্ষতির জন্য "পরবাস"-এর প্রকাশক ও সম্পাদকরা দায়ী নন। | Email: parabaas@parabaas.com | Sign up for Parabaas updates | © 1997-2025 Parabaas Inc. All rights reserved. | About Us