|

In Praise of Annada, (Annadamangal) Vol. 1 : A Book Review Chhanda Chattopadhyay Bewtra

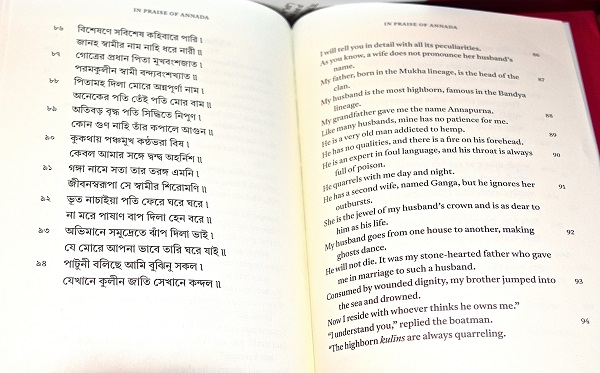

Most readers of my generation are familiar with the stories of Annadamangal, Chandimangal, Manasamangal et cetera listening to our grandmothers and aunts singing or reading the panchalis or singing them in various religious rituals (vratas). Included in the specific literary genre, the Mangalakavya, such stories are nararted in verses dedicated to many Gods and Goddesses—some minor but locally popular ones, like Shitala and Shashthi and the Snake Goddess Manasa. Many poets composed these over a period of time between 15th and 18th centuries. Together they constitute the earliest genre of Bengali literature. Mangalkavya literally means poems of benediction. The composer eulogizes the local deities or mythological figures rather than the major Vedic Gods. Many are indigenous to Bengal—as the snake goddess Manasa, the small pox goddess Shitala or the fertility goddess Shashthi. Along with the praises to the deities these songs also describe the social, cultural and religious scenarios of the rural Bengal in the Middle Ages. The deities are often portrayed in human forms, with human character flaws and emotions like envy, anger or sadness. The writing is usually in couplets with a simple rhyme form, suitable for singing or reciting orally. The imagery too is simple and rustic—involving rivers, forests, villages and fields. There are usually four parts in each Mangalkavya—Vandana (praise to the deity), Reasoning, Devakhanda (part about the Gods) and Narakhanda (part about the humans). There are many other Mangalkavyas--Kalika mangal, Rayamangal, Kamalamangal, Shivayana and Dharmamangalkavya. There are even some local subgroups like Raimangalkavya around the Sunderban area of Bengal. So far there have been no available translations of these well-loved literature. Thus, it was a pleasant surprise to see this book translated in English. Annadamangal is a collection of songs and verses dedicated to the Goddess Annapurna (Goddess of bounty of rice) who is also God Shiva’s consort and known by other names such as Sati, Uma, Parvati and Durga. The Bengali poet Bharatchandra Ray 'Gunakar' (1712-1760) composed these verses in 18th century (1752). Bharatchandra was well versed in Bengali and Sanskrit as well as Persian and Indian classical music. He was the youngest of the four children of Narendranarayan Ray and Bhabani Devi. His talent was noted by the royal court and soon he was appointed as the court poet of Maharaja Krishnachandra of Nadia who conferred on him the title of Gunakar ('Mine of virtues'). He was the first ‘people’s poet’ in Bengali language and a true representative of the transition period between medieval and modern Bengali literature. Annadamangal is his most well known work. He also translated Bhanudatta’s Rasmanjari from Maithili and wrote bi-lingual poems Nagashtaka and Gangashtaka in Bengali and Sanskrit showing his considerable expertise in Sanskrit poetry meters and rhymes. Although he was well versed in classical ragas, he wrote the Mangalkavyas in simple lyrical forms to be sung by the ordinary people. These were about the Gods and Goddesses, but he also infused a lot of ordinary human emotions and actions for them to become familiar and popular to the listeners and performers. Later on this form of singing poetry and story telling became more popular in the forms of Padavali Kirtans and other devotional songs. Almost exactly a century later, in 1853, Ishwarchandra Vidyasagar published the most authoritative Bengali edition of Annadamangal, which is still read and referred to by all. In spite of its popularity, Ananadamangal was never translated in other languages except by a Russian playwright who translated parts of the poem and used it in the musical composition of his plays staged in Calcutta. Except for the above-mentioned partial translation, this book is the first complete translation of Anandamangal in English. The Murty Classical Library of India has attempted to make available the great literary works of India from the past two millennia. Many of these classic Indic texts have never reached a global audience. Murty Classical Library deserves much praise and thanks for this effort. Literature in all Indian languages from 1800 A.D. is included. All the translations are in modern English and appear along side the original text. This series was made possible by a generous gift from Rohan Murty when he was a doctoral student of computer science at Harvard University. In collaboration with Harvard University Press, they have published English translations of many Indian classics including Tulsidas’s Ramayana, Surdas’s poems, Abul Fazl’s History of Akbar and many others. A complete list and description can be found in the website www.murtylibrary.com. An introduction, explanatory commentary, and textual notes accompany each work with the aim of making these volumes the most authoritative and accessible. Annadamangal is the only Bengali book in the collection of Murty Classical Library. It is translated by France Bhattacharya, Emerita Professor of Bengali Language and Literature at the Institut national des langes et civilisations orientalis (INALCO), Paris. France Bhattacharya had taught language, literature and culture of Bengal at INALCO until her retirement in 2001. Her researches deal with the pre-colonial Bengali literature especially from the point of view of the social, intellectual and religious history of Bengal (including Bangladesh and the states of West Bengal, Bihar Orissa and Assam). Her English translations include "Charulata" by Rabindranath Tagore, "La complainte du sentier" by Bibhutibhushan Bandyopadhyay and many others. She is the widow of the Bengali writer Lokenath Bhattacharya. Annadamangal is essentially a eulogy to Goddess Durga as Annapurna. It is written in three parts. The current edition constitutes only the first part—Annadamangal. The second and third parts are scheduled to be published in future. The second part is titled Kalikamangal or Vidya-Sundar and is mainly an erotic tale. The third part is titled Mansingha or Annapurnamangal. It describes Mughal courtly culture--Mansingha being one of the nine 'gems' of the Mughal emperor Akbar's court. Taken together they represent the transition of classics to modern Bengali literature. Annadamangal is also further divided into three parts (khandas). The first khanda starts with the invocations for the blessings of all the Gods and Goddesses and goes on to describe the disaster at the yajna of King Daksha and the demise of his daughter Sati, wife of Shiva. This is followed by Parvati’s birth, her marriage with Shiva and creation of Varanasi as the location of her Annada or Annapurna incarnation. The second khanda describes the great sage Vyas’s unsuccessful attempt of founding Vyasakashi; the third khanda narrates the story of Harihar and Bhabananda Majumder, who were essentially celestial beings born on earth in human form and were eventually the ancestors of Bharatchandra’s patron King Krishnachandra. Each khanda is divided into a number of episodes (pala) and each pala is composed of a group of poems (pada). Each pada ends with a characteristic bhanita, the signature of the composer Bharatchandra with praise and thanks to his patron king Krishnachandra.  In this volume, each couplet is numbered and translated side by side with the Bengali original on left hand page and the corresponding lines of English translation on the right hand side. This makes it easy for a bilingual reader to read both the original and the translation together. I personally find this convenient but I wonder how many of the readers would avail of it. Numerous footnotes and the index at the back are also very helpful in deciphering obscure names and archaic words. Mangalkavya books are a valuable sources of information about the socio-cultural as well as the natural environment of the medieval Bengal. Annadamangal is no exception. We find in Jaya’s advice to Parvati (pp 196, pada #349-352) an accurate description of the low status of a penniless wife back at her parents’ house. In the poem ‘Construction of Annapurna’s house’ (pp 232-238, padas #34-71) Bharatchandra has drawn a detailed list of the various birds, animals, fish and insects prevalent in rural Bengal in those days. These provide valuable historical information about this era. Author Bharatchandra was an expert in wordplay and verse making. The book is full of such clever play of words to please the sophisticated royal audience. There are numerous alliterations, puns, poetic modification of words, double entendres and onomatopoeic sounds scattered throughout the text. Also Sanskrit words are used generously. These make the translator’s job extremely difficult. Here the translator has shown her expertise by not only translating the words literally but also conveying the mood of the writings. (There are occasional exceptions pp. 468, pada #89, the Bengali phrase ‘kapaley aagun’ is too literally translated as ‘fire in the forehead’). Of course it is not possible to maintain the rhyming words of the original script or the 8-8-10 or 14-14 syllabic construction. Even the onomatopoeic sounds have lost their resonance in some places, but overall this is a tour de force of powerful and sensitive translation that will be used by scholars as well as enjoyed by lay readers for many generations to come. Much as I have enjoyed reading both the original and the translation side by side, I can’t help but wonder about the readership of this type of translated writings. Who are the target readers? The Bengali scholars back in India can easily read the original and do not need a translation, the Bengali diaspora in other countries outside India, the NRIs and the PIOs, are mostly out of touch with reading the Bengali text. For them only the translated parts would be of any interest. Ditto for the newer generation of Bengali children. I’m afraid there are very few of us who would appreciate reading in both languages. Perhaps I am being too pessimistic. I sincerely hope I’m wrong. The readers must not skip the lengthy introduction. Here the translator provides much valuable information about the life of Bharatrchandra, the historical background and perspective of Bengal in 17th and 18th centuries and a brief summary of the stories related in the text. A generous bibliography is also provided and will surely be much appreciated by the interested readers. The cover illustration and the typeface are tasteful and pleasing to the eye. In conclusion, this translation of Annadamangal is an excellent addition to the collection of early Bengali literature. I thank the translator and Murty Classical Library for their hard work. I shall definitely look forward to the remaining volumes.

|

In Praise of Annada, (Annadamangal) Vol. 1

by Bharatchandra Ray; Translated by France Bhattacharya; Murty Classical Library of India; Published by Harvard University Press, New York; 2017; Pp. 560; ISBN: 9780674660427

In Praise of Annada, (Annadamangal) Vol. 1

by Bharatchandra Ray; Translated by France Bhattacharya; Murty Classical Library of India; Published by Harvard University Press, New York; 2017; Pp. 560; ISBN: 9780674660427