Rabindranath Tagore in Germany

If I were asked who was the greatest poet India has produced, including the greatest of ancient India, Kalidasa, my firm answer would be: ‘Tagore’ … It is tragic, however, that his greatness as a poet will never be generally acknowledged, like the greatness of Goethe, Hugo or Tolstoy.[1]

These two sentences by the well-known writer Indian Nirad Chaudhuri sum up the fate of Rabindranath Tagore as a literary figure: On the one hand, they emphasise the immense importance his work receives in West Bengal and Bangladesh; on the other hand, they demonstrate the clear limits of his importance. Tagore’s influence does not transcend the confines of the Bengali language. Bengali is spoken by approximately 180 million people in West Bengal and Bangladesh. This is a larger figure than, for example, the entire German-speaking population. Yet, Bengali is considered a regional language of the Indian subcontinent (with a limited significance even within the context of the subcontinent), whereas German is accepted as a world language, as indeed most European languages are. We are all aware of the political and economic history which created such an imbalance between the languages and the cultures in the world.

Congenial translations needed!

Hence it entirely depends on the availability of congenial translations whether Rabindranath Tagore’s true worth will be appreciated beyond Bengal. Making Shakespeare, Dante or Tolstoy one’s own with the assistance of excellent translations is comparatively easy. Shakespeare has been translated into German for the last two hundred years with immense success, and is still being translated. But translating Tagore into German does not merely entail two European languages, but two languages which are divided by separate cultures, social contexts, geographical areas and religions. He who wants to translate a poem by Tagore from Bengali to German needs to bridge the gulf which separates India and Germany.

It is not easy for an Indian to admit that their national poet, Rabindranath Tagore, is hardly known in Europe. Although the Indian subcontinent entered the sphere of modern World Literature through Tagore, this has become a fact of history now. Today Tagore is no longer a vibrant, dynamic element of World Literature, he no longer influences the intellectual horizon of a large readership and inspires writers outside Bengal. For Bengalis, Rabindranath Tagore continues to have a powerful, sometimes overbearing cultural presence.

|

| Visinting a youthgroup in Germany, 1930 |

Many Germans may feel that Tagore would best be forgotten. The mystical vagueness of his poems and his lyrical prose may have enthralled European readers for some years, but they could not pass the test of time. These poems were rendered into English by the poet himself and then translated into German by German translators. Tagore’s own English rendering does not merit the term “translation”. These texts were at best paraphrases. He transformed his finely chiselled Bengali verses into rhythmical English prose. In the process he often simplified or even trivialised the content by leaving out some of the more complex ideas and evocations and by adding new material. It is generally agreed that, whatever be the inherent worth of these English texts, they do not echo the intricacy and vigour and musicality of Tagore’s original poetry. Hence I call the German version of Tagore’s poetry “doubly watered-down”: first watered-down by Tagore himself through his English prose texts and then again by adopting them for the German.

If we examine the kind of poems Tagore selected for translation, we realise that they were predominantly his “spiritual” or “mystical” poems. He must have presumed that they especially appeal to Western readers, and he was not mistaken. But in the bargain, Tagore sacrificed a large spectrum of his themes, styles and moods which he did not present to the non-Bengali public. Tagore’s selection of poems helped to reinforce the image of Tagore as a mystic.

Tagore’s visits to Germany

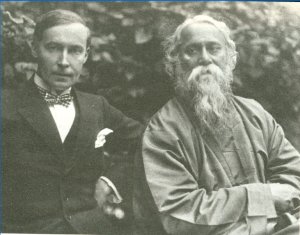

|

| With German intellectuals in 1926 |

Tagore’s poetry had a direct appeal to Germans of that generation because his poetry (or whatever he chose to give to the West) was exotic, had a romantic flair, was imbued with spiritual idealism - and yet in all its strangeness it was still easily accessible. His poetry embodied a religious imagery, essentially Vaishnava in character, which was innovative for Western ears. To them, this culture of emotions was unfamiliar in its directness, its eroticism and involvement with nature and the cosmos - and yet, the poetry was totally comprehensible. Tagore himself, attired in his flowing, dark gown and with his white beard and serene face, radiated a certain erotic energy.

Tagore revisited Germany in 1926 and 1930. Although the early biographies of Tagore characterize Tagore’s three visits to Germany as unmitigated success stories, Tagore himself preferred to take a more detached view. In 1921, he wrote to a friend:

It has been a wonderful experience in this country for me! Such fame as I have got I cannot take at all seriously. It is too readily given, and too immediately. It has not had the perspective of time. And this is why I feel frightened and tired at it and even sad.[2]

The German-speaking press was by no means unanimous in its praise. There were three major points around which the criticism of the press revolved: (1) Tagore, a Hindu, wanted to influence Christians in their faith and ultimately convert them to Hinduism. (2) German writers deserved a slice of the Indian writer’s enormous fame, as they were no less talented and relevant in their writing. (3) Tagore’s seeming “oriental lethargy”, “bloodlessness”, “Indian mildness” was inimical to German or European “dynamism”, to its “action-oriented” mindset. At that point of history, this European mindset was deperately needed to support the reconstruction of the German nation after the First World War.

Rilke, Zweig, Thomas Mann, Hesse

The adulation Tagore received from the masses rather deterred serious German fellow writers from making an evaluation of Tagore’s literary merit. They even shied away from meeting him. Yet, there were two of Germany’s eminent contemporary writers who met Tagore and two others who took a serious interest in him and acclaimed him as a figure of consequence.

Let me first turn to Rainer Maria Rilke (1875-1926). Even a few months before Tagore was awarded the Nobel Prize, Rilke recognized Tagore’s importance which he expressed in a letter to Lou Andreas-Salomé[3]. Rilke had heard another famous writer, the Frenchman André Gide, read out his French translation of Gitanjali which had impressed Rilke considerably. Further, Rilke mentioned his praise of Tagore in a letter to the German publisher Kurt Wolff[4]. At the time, Wolff had just secured the English manuscript of Gitanjali for his publishing firm and it was already being translated. Quick to see his advantage, Wolff offered to Rilke that he translate Gitanjali into German, as Gide did into French. Rilke considered the offer deeply for some time and then rejected it. This is the explanation he gave in his letter to Kurt Wolff:

I do not find within myself that

irrefutable call for the proposed assignment, from which alone could emerge a

definitive and responsible work. Although much in these stanzas has a familiar

ring, it seems, so to speak, to be borne towards me on a tide of unfamiliarity…

This may be partly due to my meagre acquaintance with the English language.[5]

Rilke is not known to have commented on Rabindranath Tagore thereafter, not even in 1921 when the latter was in the zenith of his fame.

Stefan Zweig (1881-1941), the Austrian writer, and Thomas Mann were introduced to Rabindranath Tagore in the summer of 1921. True to their temperament, their reactions to Tagore were quite opposite to each other. Zweig, the suave cosmopolitan and altruistic humanitarian, had visited India in the winter of 1908/09. He was appalled by the poverty and misery he saw and later bemoaned the feeling of “unsurmountable unfamiliarity”[6] that overcame him when he faced India’s tumultuous life. Yet, he maintained an active interest in India’s freedom struggle and in her intellectual life. He also observed Rabindranath’s rise to fame in Europe and exchanged views on him with that other European intellectual with a keenly critical and supportive interest in India, Romain Rolland. So when Kurt Wolff informed Stefan Zweig that Tagore was to change trains in Salzburg en route to Vienna, Zweig who resided in Salzburg, jumped at the chance to meet him. The short meeting was deeply meaningful to Zweig. Returning home, he immediately penned a letter to Wolff in which he wrote:

Thank you very much for the information regarding Tagore’s travel programme. This enabled me to spend half an hour in his company today at Salzburg railway station while he changed trains. Thanks to you, I have encountered this great personality, of whom I formed a strong and profound impression.[7]

Zweig continued to observe Tagore’s impact on the European public. Zweig unequivocally appreciated Tagore’s message of humanism, while he was critical of Tagore’s ostensible penchant to seek publicity. When Tagore chose to visit the philosopher Count Hermann Keyserling in Darmstadt for a week, Zweig commented that Tagore “was unwise enough to have his visit publicly announced”[8]. And in 1926 Zweig criticised Tagore for this “new mania of travelling around Europe as a missionary of the spirit” which he calls a “contageous disease”[9].

Thomas Mann (1875-1955) was both less sympathetic and more complex in his reaction to Tagore. Initially, he even refused to meet him. In 1921, Mann was approached by Hermann Keyserling to write an essay on Tagore which was meant to publicize the “Tagore-Week” Keyserling planned in Darmstadt. Mann refused and was also unwilling to go and attend Tagore’s lectures. In a letter typical of Thomas Mann, he explained the reasons for his negative response.

Dear and Respected Count Keyserling,

I cordially thank you for your letter. It exudes so much enthusiasm that I almost packed my bags and went to Darmstadt. However this would have been easier than writing an article, particularly one canvassing for the famous Indian of whom I have, whether you believe it or not, no understanding, or almost none, until now. […] The image I have always had of him is picturesque but pallid. Surely I do him an injustice in assuming that the subjective pallor of this image reflects reality; in presuming him to be a typical Indian pacifist, animated by a somewhat anaemic humanitarian spirit and a mildness which I deemed almost hostile in the years I spent engrossed in violent emotional conflict. Surely the man is totally different. Since I understand from your letter that he has made a deep impression on you, he must be great.[10]

Thomas Mann alluded to the well-known duality between European strength and Indian “pallor”, “mildness” to which he gave a distinctly negative connotation. The letter was cleverly crafted. Mann had his say on Tagore clearly and then made a rhetorical volte-face by declaring: “Surely the man is totally different. Since […] he has made a deep impression on you, he must be great.” In this manner, he could pronounce his reservations and still hope not to offend the famous Count.

A few weeks later, however, Thomas Mann was unable to avoid coming face to face with the “pallid” Indian poet. Mann lived in Munich and Tagore arrived in that city for several lecture engagements. Tagore delivered a lecture at the University, and on the next day Kurt Wolff, Tagore’s German publisher, invited some people from the intellectual élite to a reception at his home. Thomas Mann and his wife Katja attended both the lecture and the reception. Mann noted down in his diary the impressions of this second day:

At 11 drove with K[atja] to K.Wolff’s for R.Tagore’s lecture. Select gathering. The impression of a fine old English lady gained strength. His son was brown and muscular - a masculine type. I was introduced, said ‘it was so beautiful’ and pushed K. forward: ‘my wife who speaks english better than I’. He did not seem to grasp who I was.[11]

What had happened? Tagore’s long robe and his flowing hair had reminded Mann of a “fine old English lady” which was a rather rude remark. When Mann was introduced to Tagore, he avoided a conversation by pushing his wife forward and claiming that she speaks English better than he and hence should be spoken to. After thus studiously avoiding contact with Tagore, Mann should not have been too surprised that the poet did not recognise his German colleague, the famous Thomas Mann. Yet Mann’s pride must have been bruised.

Hermann Hesse (1877-1962) never met Rabindranath Tagore although one would have expected him, more than anybody else, to seek and maintain a contact with the Indian poet. Hesse had been involved with Indian Thought since his childhood. His parents were Protestant Christian missionaries in South India. His maternal grandfather, Heinrich Gundert, had been a pioneering scholar of the Malayalam language and culture. Hesse, like others in his time, naïvely conceived of India as a country of spiritual perfection and angelic human beings. This romantic notion was bound to be shattered when Hesse set out on his one long trip outside Europe which took him to Sri Lanka and Indonesia in 1911. He was unable to set foot on mainland India as due to illness his trip had to be cut short. But he witnessed Hindu and Buddhist culture. Hesse was disillusioned with Asia, but then his expectations had not been realistic. He published his diary notes and returned to his experience again and again in letters, short stories and essays. Slowly, his disappointment transformed itself into a new vision of India which was less idealistic. Formerly, Hesse had believed in the dichotomy of the “spiritual East” and the “materialistic West”. Now he chose to perceive an undercurrent of mysticism in both East and West. He envisioned a spiritual unity encompassing both.

The best-known fruit of Hesse’s Indian experience is his “Indian novel” Siddhartha. When Rabindranath Tagore toured Europe in 1921, Hesse was deeply involved in writing this novel of an Indian spiritual aspirant’s path to fulfilment. He lived in the Ticino mountains in southern Switzerland almost like a hermit. The idea of travelling to Germany or Austria to meet Tagore must have been far from his mind. And yet, Hermann Hesse kept an eye on the intellectual developments of his time. He reviewed three books by Tagore (Gitanjali, The Gardener and The Home and the World) and expressed his views in several letters. The last letter in which Hesse referred to Tagore is from 1957. Hesse was not fascinated by Tagore to the same degree as Stefan Zweig, Romain Rolland and Hermann Keyserling were. Strangely, Hesse considered Tagore’s writing as too European and not of exceptionally high quality, although he did laud the nobility and dream-like beauty of his texts. Hesse did however fully support Tagore’s novel The Home and the World concluding his review with the words: “…the more people read this book the better.”[12]

In his last letter, Hesse commented on Tagore’s “partial eclipse in the West” after the Second World War. Hesse opined that Tagore had been “a fashion” in the 1920s and now had to pay the price for being out of fashion. Yet,

in some minds and hearts the effects [of reading Tagore] have lived on and borne fruit, and this continuing influence - impersonal, silent and in no way dependent on fame and fashion - may in the final analysis be more appropriate to an Indian sage than fame or personality cults.[13]

Rabindranath Tagore in Germany Today

|

| With his publisher Kurt Wolff in 1921 |

After Kurt Wolff desisted from publishing, a new phase began for Helene Meyer-Franck: she learnt Bengali for the sole purpose of reading Tagore, her “dear Master”, in the original. It was a lonely fight in her small town near Hamburg, as she was virtually on her own. However, she learnt to read Bengali sufficiently well to translate into German three novellas and a collection of poetry. The novellas were published as early as 1930, but they left no visible trace because of the Nazi Reich emerging in 1933. Helene Meyer-Franck had to wait until after the Second World War before she was able to publish her second slim volume. Soon thereafter, first her husband and then she died. As a result, her initiative to translate Tagore directly from Bengali was not continued, and there was nobody to emulated her. In the 1950s, the old translations from English, published in the 1920s, were republished in West-Germany, and in some cases new translations of these weak and flawed English texts came out.

Communist East-Germany had a special relationship with Tagore. The latter’s internationalism endeared him to the regime, and his work was given political weight. Tagore’s books were translated into German in much larger numbers than in the West. Yet, these translations were generally of doubtful quality. Several anthologies contained translations from the English and from the Bengali side by side; other books were translated via Russian. Then there were so-called team-translation, i.e. a Bengali knowing little German and a German knowing little or no Bengali teamed up to produce a translation. None of these methods were at all satisfactory, and they did not serve to enhance Tagore’s reputation as a figure of World Literature. As far as I can see, only one person in erstwhile East-Germany mastered Bengali well enough to produce a competent translation on her own; that was Gisel Leiste, who translated one major novel, Gora.

It was not until the 1980s and 1990s that fresh direct translations were brought out, first by Alokeranjan Dasgupta (one volume) and then by Martin Kämpchen (three volumes). They were brought out by small, specialised or by theological publishers. What Tagore needs acutely, however, are mainstream literary publishers who market his works. This need is soon going to be fulfilled by a volume of love poetry, translated by Martin Kämpchen, brought out (in February 2004) by a premier literary publisher, Insel Verlag, in its series Liebesgedichte. Another publisher, Verlag Artemis & Winkler, is scheduled to bring out a larger volume of Tagore’s Selected Works, edited by Martin Kämpchen, in its series of Classics of World Literature.

I believe that in Germany Tagore’s time has now arrived. Apart from the fact that any great literature has a claim to be noticed and respected throughout the world simply because it is great literature, I wish to identify three areas in which Tagore’s ideas and ideals have a strong relevance for us today:

(a) Ecology. - Rabindranath Tagore’s love of nature was inspired by the awareness that all living beings, including animals, trees and plants, are endowed with a soul. On this level of consciousness, human beings are equal with “low” creatures and plants. We are all co-creatures of God’s creation. Accordingly, Tagore’s praise and worship of nature is born of a deep spirit of togetherness and feeling of a creational bond between humans and nature. Such a sense of unity is missing in modern Western ecology. It tends to emphasise the usefulness of nature and the necessity of a natural environment for the practical survival of mankind. Thus, with his poetry and his essays, Tagore can inspire a deeper understanding of and togetherness with the natural environment.

(b) Education. - Rabindranath Tagore’s ideas of education continue to be relevant. He wanted to unfold the entire personality through music, songs, dance, theatre, art, contemplation of nature, meditation and social service. The Indian subcontinent has strayed from these ideals, and in Western countries, too, the demons of “usefulness” and “efficiency” have to be tamed by the intentless, playful activity of Tagorean education.

(c) International understanding. - Rabindranath Tagore’s deep yearning for harmony among men, achieved through mutual tolerance and simplicity of life, is as worthy of imitation now as it was then. It is not enough to nourish dreams and circulate hopes. Tagore has demonstrated to us how much one inspired human being is capable of achieving among men. Tagore descended from his dreams into reality and gradually worked out an understanding between human beings in his school, his university and his interaction with the wide world.

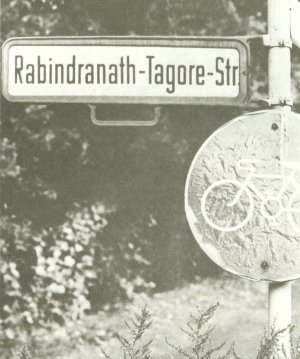

|

| Rabindranath Tagore Street in Berlin opened in 1961 (Photo: Christian Zeiske, Berlin) |

Dr Dr Martin Kämpchen is a writer on India and a translator of Tagore from Bengali to German. He lives at Santiniketan, India. For more information visit his website www.martin-kaempchen.com.

[1] Nirad Chaudhuri: Thy Hand, Great Anarch! India 1921-1952. Chatto & Windus, London 1987, p.596.

[2] Rabindranath Tagore: Letters to a Friend. Edited by C.F.Andrews. Macmillan, New York 1929, p.171.

[3] See Rainer Maria Rilke - Lou Andreas Salomé: Briefwechsel. Edited by Ernst Pfeiffer. Insel Verlag, Frankfurt 1975, p.300 (dated 20th September 1913).

[4] See Kurt Wolff: Briefwechsel eines Verlegers 1911-1963. Edited by Bernhard Zeller and Ellen Otten. Verlag Heinrich Scheffler, Frankfurt 1966, p.136f.

[5] Op.cit., p.138f.

[6] Stefan Zweig: Benares: Die Stadt der tausend Tempel. In: Zweig: Begegnungen mit Menschen, Büchern, Städten. S.Fischer Verlag, Berlin/Franklfurt 1956, p.260.

[7] Kurt Wolff: Briefwechsel eines Verlegers. p. 414.

[8] Romain Rolland - Stefan Zweig: Ein Briefwechsel 1910-1940. 1st vol. 1910-1923. Verlag Rütten & Loening, Berlin 1987, p.640f.

[9] Rolland - Zweig: Briefwechsel. 2nd vol. 1924-1940. p.187.

[10] Thomas Mann: Briefe 1889-1936. Edited by Erika Mann. S.Fischer Verlag, Frankfurt 1961, p.188f.

[11] Thomas Mann: Tagebücher 1918-1921. Edited by Peter de Mendelssohn. S.Fischer Verlag, Frankfurt 1979, p.529f.

[12] Vivos Voco (Leipzig), vol. 1, Nov. 1920, p.817.

[13] Hermann Hesse: Preface. In: Later Poems of Tagore. Translated and with an introduction by Aurobindo Bose. Peter Owen, London 1974, p.7.

For more comprehensive accounts of Tagore’s impact on the German people, please refer to my books: Rabindranath Tagore and Germany: A Documentation. Max Mueller Bhavan, Calcutta 1991; Rabindranath Tagore in Germany. Four Responses to a Cultural Icon. Indian Institute of Advanved Study. Shimla 1999; My Dear Master. Correspondence of Helene Meyer-Franck / Heinrich Meyer-Benfey and Rabindranath Tagore 1920-1938. Edited by Martin Kämpchen and Prasanta Kumar Paul. Rabindra-Bhavana, Visva-Bharati, Santiniketan 1999.

Published in Parabaas July 25, 2003.