Rabindranath

Tagore and Srečko Kosovel:

A Joint

Perspective in a Disjointed World

Ana

Jelnikar

In the 1920s, at the

height of Rabindranath Tagore’s reputation in continental Europe, the Slovenian

poet Srečko Kosovel wrote the following poem:

In

green India among quiet

trees

that bend over blue water

lives

Tagore.

Time

there is spellbound, a cerulean circle,

the

clock tells neither month nor year

but

ripples in silence

as if

from invisible springs

over

ridges of temples and hills of trees.

There

nobody’s dying, nobody’s saying

goodbye—life

is like eternity, caught in a tree . . .

(‘In Green

This symbolist meditation on timelessness and eternity makes for one of

Kosovel’s most explicit tributes to Tagore to be found in his creative writing.

A closer look at Kosovel’s collected works however reveals that the Indian poet

is by far the most often referred

to foreign author. He gets a mention over fifty times. Leo Tolstoy, another

figure Kosovel admired, is referred to thirty times and Romain Rolland fifteen.

In fact, Srečko Kosovel read Tagore’s works throughout his short and

prolific life, convinced as he was that here was someone able to show a new

direction out of the crisis Europe in general and the Slovenian people in

particular were experiencing in the disillusionment of the post-Great-War

years. When Tagore’s works were not yet available in the Slovenian translation,

as was the case with Nationalism, Sadhana and Personality, he got hold of them in German and Serbo-Croatian, the

languages he could read alongside French, Italian and Russian.[1]

Taking ‘lessons’ from Tagore’s philosophical writings, he urged his artistic

colleagues to do the same. When in 1925, aged twenty-one and within months of

his untimely death, he was getting his first poetry manuscript ready for

publication, he decided to give it the title Zlati čoln (The

Golden Boat) in direct allusion to Tagore – his spiritual and

literary mentor.

Today regarded as

Slovenia’s foremost modernist, avant-garde voice of the inter-war years, Srečko

Kosovel (1904–1926) started out as a poet in a more or less traditional vein. It

was his potential for growth and change that marked him as a modern. In the

last four years of his life, he produced a large body of poetry (over a

thousand poems, it seems), impressive for its stylistic experimentation and the

need to push out the boundaries of acceptable poetic expression. Searching for a form that

would reflect and engage with the disoriented reality of the post-world war

era, Kosovel kept his finger on the pulse of the present. Convinced also of

the value of bringing contemporary literary currents and thought to bear

critically on the Slovenian reality, in the 1920s, he was engaging

with a great many of the major “isms” of his day: from post-impressionism and

Symbolism to German Expressionism, Italian Futurism, Russian Constructivism,

and French Dadaism and Surrealism, much of which was mediated to him through

new, eclectic Balkan Zenitist movement.[2] This meant –

drawing on the poet’s own definition – learning

from European artists, rather than following them in blind imitation. It was

in this largely European setting that Tagore’s writings came to him as a major

literary and philosophical voice of the time. Why did Kosovel feel so drawn

to the Indian poet?

While Kosovel’s numerous

stylistic metamorphoses as a poet, in which he successfully combined new means

of expression with traditional themes and local concerns – his shift from a

traditional lyricist to a modernist – can be fruitfully related also to his

reading of Tagore, in this paper, I will limit myself to exploring the

unexpected links and connections Kosovel surmised between himself and Tagore. This

will help us understand why he sympathetically reached out to the Indian

poet, as it will also showcase a perception different to the more familiar

interpretations of Tagore’s reception within Europe, in which orientalist

tropes are closely aligned with imperialist interests. Moreover, as we consider the

particulars of Kosovel’s historical positioning, it will become clear that

Tagore and Kosovel in fact shared a remarkable set of preoccupations against

their respective backgrounds. For like Tagore, Kosovel too understood the

pressures and dilemmas pertaining to a culture dominated by another.

Interestingly too, with regard to those pressures and dilemmas, he offered some

remarkably ‘Tagorean’ answers.

Slovene’s Initial Response to

Tagore

When Tagore received the Nobel Prize for literature in 1913, he was not

only the first non-Westerner to be accorded the honour, but also became, in the

words of Amit Chaudhuri, “the first global superstar or celebrity in

literature”. Slovenes too participated in the ‘Tagoreana’ from the early days

of the poet’s international reputation, and their response, as elsewhere in

Europe, was shaped by their specific concerns. But perhaps unlike everywhere

else, in Slovenia Tagore became included in the school curricula and remains to

this day a household name in any moderately educated family. The tribute to him

has also been expressed by having one of his aphoristic poems carved into a

signpost in the mountains – an unusual, but not an entirely surprising gesture

for a country commonly dubbed as a nation of poets and athletes.

Going for a hike above the town of

Whatever the case may be, the two interpretations of

the above quote seem paradigmatic for a small nation, living at the crossroads

of many competing cultures, Slavic, Romanic, Germanic, and others. They

signpost the characteristic tension Slovenes have always felt towards home and

the world, where, particularly in matters of culture and literature,

ethnocentric and cosmopolitan directions have vied for supremacy since the

first stirrings of national consciousness in the sixteenth century. How then

was the Indian champion of world humanity received amongst the Slovenes in

general and by Kosovel in particular?

Soon after 1913, it was the enthusiasm (backed by

translation) of some of

Slovene’s initial response to Tagore, however, was

largely dominated by extra-literary factors rather than any authentic

appreciation of the writer’s sensibility. Slovenes had their own political axe

to grind with the Austrians. In the first substantial article entitled Last year's rivals for the Nobel Prize

(1914), Tagore’s winning of the Nobel Prize is juxtaposed to the defeat of the

Austrian poet Peter Rossegger. In the same year that Tagore’s name was put up

for the consideration by the Swedish committee, the Austrians had their own

candidate, Peter Rosseger, whose name for Slovenes was associated less with

literary credentials than with an aggressive Germanization policy pursued

against Slovenes in Southern Carinthia and Southern Styria.[4]

Against this background, the author of the article

sets “a spiritual giant of enormous horizons” in opposition to a parochial

writer who “fans the flames of nationalist hatred”. Tagore is celebrated for

his love of humanity as opposed to love of nation. His patriotic songs are not

“boisterous fighting hymns”, but seen as perfect expressions of “his universalism”.

Tagore's patriotic sentiments are admired for their lack of anger or envy

towards the oppressors, for upholding the high moral ideal that “the love of

humanity is above all nations” (Lokar 1914: 246). In spite of the narrow

politicized framework in which the discussion of Tagore is positioned by this

article, the poet’s vision of

Indeed, Tagore critiqued both imperialism and

its anti-colonial nationalist derivation, to eventually argue that imperialism

and nationalism are two faces of the same monster (cf. Tagore 2002). After his

own brief involvement with the Swadeshi movement, the first popular

anti-colonial movement in

It was precisely this high ideal underscored by the

article that was to resonate so strongly with Kosovel, who aimed for a

like-minded resolve with respect to Slovenes and their struggle for political

and cultural autonomy. In fact, from its beginning, Tagore’s popularity in

Slovenia was connected less with the romantic side of Orientalism that looked

towards India for a redemptive spiritual injection and saw in Tagore above all

“the exotic and bearded Oriental prophet” (Petrović 1970: 13), than with a

sense of identification with the poet and his people, derived from a perceived

common goal of striving after political and cultural independence. For it was the political circumstances of

the early decades of the twentieth century, as Slovenes were caught in

the cross-fire of a number of aggressive nationalisms (external and internal), that in large part galvanised Kosovel to

grapple with the problematic of nation, nationalism and nationhood. In

an important essay he wrote in response to Tagore’s book Nationalism and

entitled it Narodnost in vzgoja (Nationhood and Education), we see him

striving for a definition of Slovenianness that – even as it

remained sensitive to the particular needs of his people and espoused their

right to self-determination – refused to yield to an inward-looking or a

separatist stance.

Srečko Kosovel: Life and Background

For a country that achieved full

political sovereignty nineteen years ago, Slovene language and

literature can be looked at as mainstays of cultural identity, and are often

imbued with a strong nationalistic sentiment. It has been argued that smaller

Slavic cultures have forged an exceptionally close link between language,

literature and politics. Literature

has often served as a sacred shrine to national values, and language itself has

been seen as a national value. Given this importance, violations of

traditionally sanctioned forms have constituted, for some, direct attacks on

the national body itself (Djurić

2003: 80; 66). Real and imagined threats to Slovenian existence

in the inter-war period created a climate in which traditionalism and

domesticity were the prescribed modes. Kosovel understood this, and so kept his

most radical avant-garde experiments in the drawer, away from prying eyes,

where they were to remain for the next forty years, before given due

recognition by the literary establishment.

Born in 1904, in the small town of

Tomaj was a village of a slightly

more than 600 inhabitants, predominantly wine and wheat producers, battling the

harsh conditions of the wind-swept, arid landscape of the Karst. Anton Kosovel

was also a musician (a choirmaster and an organ player) with an avid interest

in farming. He made sure that his children were given a broad education

spanning cultural and economic matters. By the age of seven, the

Kosovel children were learning French, Russian and German, and the Kosovel

household attracted artists and intellectuals seeking a haven for open

discussion in what were politically turbulent times.

After the dissolution of the

Austro-Hungarian Empire in 1918, Slovenes joined the newly-founded nation state

of South Slavic peoples: the

If Srečko inherited some of

Anton’s passion for Slovenian matters (and notwithstanding the fact that

Srečko did not follow his father’s wishes to become a forester and help

develop the region), he took from his mother, Katarina Stres, a defiant streak

and a deep curiosity about the world. As a young girl with little formal

education, Katarina had rebelled against her own parents, refusing to marry the

man that they had chosen for her. She ran away from her native

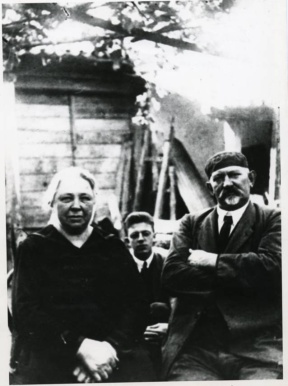

Srečko with his parents Srečko’s happy childhood

years were interrupted by the outbreak of the First World War. A new front

opened up along the river Soča (Isonzo), not even fifteen miles to the

west of Tomaj, where some of the fiercest fighting between the Austrians and

Italians took place. His parents sent the twelve-year-old boy, together with

his sister Anica, to For

the remaining decade of his short life, Kosovel lived in Ljubljana, returning

home only for the summer and during term breaks. He harboured ambivalent

feelings towards his newly adopted home, at once a new center of Slovenian

culture and the provincial backwater of an erstwhile Empire. In many ways,

Trieste was more a “home” to Kosovel than was Ljubljana. Its importance for

Kosovel is unsurprising, given that it was the closest urban center to his

childhood home, and that it was of great historic and cultural importance for

the Slovenian people. While today the city is predominantly Italian—Slovenes

forming a small ethnic minority—turn-of-the-century Trieste had a larger

Slovenian population than Ljubljana. It was an important center of Slovenian

culture, where its institutions were established soon after the revolutionary

year of 1848, and the Slovene political party Edinost (Unity) was founded there as early as 1874. Before

the war, the Kosovel children would often take in a play by Strindberg or Ibsen

at the popular Teatro Verdi or Teatro Rossetti, as well as performances at the

Slovenian Theater House (founded in 1903 as the first Slovenian theater). In the decades leading up to the

collapse of the Empire, however, the city’s multiethnic composition, thoroughly

shaken up by war and further unsettled by old, revived enmities between

Italians and Slavs, crumbled into factions vying for political pre-eminence,

with Slavic propagandists championing the rights of the Slovene and Croat

populations and Italian nationalists wanting to “redeem” the city, seeing it as

a natural part of a unified Italian body politic. Ethnic bigotry erupted, and

with the political barometer decidedly pro-Italian, Slavs became the butt of

persecution. In 1920, the seat of Slav cultural

life, the Narodni Dom (National

House) was torched by a mob with the consent of the Triestine police and

authorities. This signaled the beginning of enforced assimilation, a doctrine

which gained broad legitimacy as fascists came into power in 1922. Policies

adopted between 1924 and 1927 “transformed five hundred Slovene and Croatian

primary schools into Italian-language schools, deported one thousand Slavic

teachers (personified as ‘the resistance of a foreign race’) to other parts of

Italy, and closed around five hundred Slav societies and a slightly smaller

number of libraries” (Sluga

2001: 48). Kosovel’s father was forced to retire for refusing to abide by the

Italian-only language policy, and was replaced by a more pliant Slovene, Ivan

Kosmina. This brought the family severe financial difficulties. They even lost

the roof over their heads, since their accommodation was tied to Anton’s

teaching post. By 1926 non-Italian names had to be Italianized. By 1927,

shortly after Kosovel’s death, the use of Slovene was prohibited in public.

Periodicals were banned and political parties dissolved. Many intellectuals and

artists were forced into exile. If Italian irredentism was one major source of

grievance and concern for Kosovel, the other was Yugoslav unitarism, as the

centralising tendencies of His task therefore became twofold: to show that

“nationalism was a lie” (Kosovel 1974: 31) and to salvage the concept of narod (a people) from being hijacked by

nationalism: “A narod for us can only

ever mean a nation which has freed itself from nationalism” (Kosovel 1977:

624). Driving a wedge between nationhood and nationalism meant for Kosovel

demarcating the important sense of national selfhood from a self-indulgent

celebration of one’s own identity. Nationhood required a measure of

selflessness, lest it should lead down “the wide road of national egoism”

(Kosovel 1977: 67). Vital input for thinking through these issues Kosovel got from

Tagore’s book Nationalism (1917). The wider political background of Kosovel’s life is important, since it is

precisely from this historical juncture that Kosovel gained his sense of

intimacy and shared concerns with Tagore. When he thought of the troubles of Primorska (the Slovenian Littoral) under

Italian rule, he aligned them with the “unnatural act” he saw in the

“colonisation of the non-European peoples” (Kosovel 1977: 65–66). Therefore, rather

than seeing in Tagore’s attraction for Kosovel yet another predictable response

coming from the West from within the romantic and orientalist tradition of

Europe’s enchantment with Eastern thought and art, I propose we see it instead

in terms of a situational identification where sympathies are forged

between individuals and inspirations derived from a sense of shared

predicaments (cf. Hogan 2004: 26).

It is indeed

true that some of the qualities Kosovel perceived in Tagore, notions such as

“simplicity”, “naturalness”, “child-likeness”, as also his comparing the power

of Tagore's language to that of the gospels (Kosovel 1977: 509, 558, 561), are

all part and parcel of the dominant tropes that guided the imaginations of

Europeans when they turned towards the East in the early decades of the

twentieth century, and which have since been criticized for their orientalizing

thrust. But to stop here would be to stop short of more fully appreciating why

Tagore was so important to Kosovel or how even some of these same concepts

might have actually contributed to the project of (cultural) emancipation both

poets shared. Without disputing the basic premise that when Western thinkers

drew on Eastern thought – the religious and philosophical ideas of India, China

and Japan – they did so in line with their own goals and pursuits, these ideas would

often serve to question Europe’s established role and identity, rather than

assert it (cf. Clarke 1997: 27). The talk of “crisis” or “sickness” besetting

Western civilization and of the need to turn “Eastwards” for cure that constitutes

the more radical early 20th-century orientalist discourse, certainly

applies to Kosovel, and can explain some of his enchantment with Tagore. Furthermore, as Imre Bangha has pointed out with

respect to For Kosovel, reading Tagore meant encountering a voice

that shared some of the age’s deepest cultural and intellectual concerns,

spanning nationalism, scientific and technological revolutions,

environmentalism and feminism alike, and which helped him think through some of

these pressing issues. It is therefore more in the spirit of parity that

Kosovel approaches Tagore, as opposed to an Eastern guru at whose feet one

should sit, or, following the colonial mindset, “an Oriental” who deserves to

be patronized. Kosovel turns ‘East’ He developed this sense intimacy with the Indian poet

particularly as he thought of the troubles of Primorska under Italian rule. He also understood that, like Tagore,

he had been delegated to the large ideological constructs of the “East.” Here I

am referring to the tradition of representation that predates fascism and goes

back to the Enlightenment, in which “ In that sense both Tagore and Kosovel were projected

as belonging to an inferior and governable race, Indian and (Balkan) Slav

respectively, with We happen to be living at the crossroads of Western

and Eastern Europe, on the battlefront of Eastern culture with Western, in an

age which is the most exciting and the most interesting in its multiplicity of

idioms and movements in politics, economics and art, because our age carries

within itself all the idioms of the cultural and political past of Europe and

possibly the future of Asia (Kosovel 1977: 178). The reference to Asia is no doubt an allusion to Tagore’s own

understanding of It will not do, as Tagore wrote in his essay Purba o Paschim (East and West), thinking of the relationship between the British

and the Indians, “to blame them alone”. We have to be prepared to “take the

blame on ourselves” (Tagore 1961: 138). Both Tagore and Kosovel, for all their

affection for their respective countries became their respective countries’

harshest critics. Both transformed – what Ashis Nandy has so aptly

characterized with reference to Tagore – “passionate self-other” debates into

“self-self” debate (Nandy 2005: 82). In the same way that Tagore, despite the violence and

humiliation of foreign rule, refused to succumb to a dismissal of everything

British or, conversely, an uncritical valorization of everything Indian,

Kosovel too made it a point to discriminate between imperialist forces that

deserve all reprobation and Italian culture which may or may not be implicated

by these forces. Both strove to override politics in an open acceptance of what

they felt was commendable in any given culture, laying themselves open to

charges of denationalized surrender. In a lesser-known poem entitled “Italian Culture”,

Kosovel makes it quite clear that his quest for liberation had to be larger.

With a reference to Gandhi, this poem once again demonstrates how Kosovel was

searching for alternative cultural models: as Slovenian institutions were under

attack in The Slovenian National House in The Workers House in Wheat fields in Fascist threat during the elections. The heart is becoming as tough as a rock. Shall Slovenian workers’ homes continue to burn? The old woman is dying at her prayers. Slovenianness is a Progressive Factor. Humanism is a Progressive Factor. A humanistic Slovenianness: synthesis of evolution. Gandhi, Gandhi, Gandhi! Edinost*

is burning,

burning, Our nation, choking, choking. (Kosovel 2008: 137) What makes this poem interesting is that the crisis it describes is

transformed into a self-questioning, in which violence and retaliation as a

means of asserting one’s identity (evocation of Gandhi is appropriate indeed)

are superseded by an universalist and a humanist perspective. Slovenianness, if

it is to progress in evolution, must not surrender humanist ideals. Or, as he

wrote to his French teacher Dragan Šanda: “A nation only becomes a nation when

it becomes aware of its humanity” (Kosovel 1925, 1977: 323–324). Both Kosovel

and Tagore believed in the perfectibility of human beings. In line with some of the most imaginative

anti-colonial or anti-imperialist responses across the globe, Tagore’s and

Kosovel’s liberational stances thus commanded a pull away from separatist

nationalism towards a more integrative and pluralistic view of human community.

What they sought was much more than the simple departure of the colonizers:

there had to be a complex transformation of the colonized, else alien hegemony

would merely be replaced by a home-grown one. The universal philosophy of Tagore clearly struck a

chord with Kosovel who saw his native region affected by imperialist forces,

perceived as similar to those that subjugated Stressing the links between the inter-war avant-gardes, the colonies and anti-imperialist

consciousness, Brennan submits that “the Russian Revolution […] was an

anticolonial revolution”. This he takes to mean in “its sponsorship of

anticolonial rhetoric” which “thrived in the art columns of left newspapers,

cabarets or the political underground, mainstream radio, the cultural groups of

the Popular Front, Bolshevik theater troupes”, meeting with responses and

contributions from “the various avant-garde arts”. Brennan cannot overstate the

implications of the revolution for the “the idea of the West”. It “delivered The idea of social revolution was now combined with

anti-imperialist thought. This was because an analogy was being made between

the capitalist’s exploitation of the worker and imperialist’s exploitation of

the colonized. For Kosovel – no blind admirer of the Soviet experiment – the

“proletariat” was more or less interchangeable with the “suppressed” or

“humiliated man,” (in Slovenian, like in Bengali, the word for “man” is gender

neutral) suggesting a more universal human condition. Though the poet was not

himself always above a dualistic view of the world that pitted suppressors

against the suppressed, in the final instance he did not permit himself the

luxury of thinking that the solution to the “world problem” lay in a simple

reversal of these dichotomies and the power structures they entailed: “In our

innermost being, there are no classes or nations” (Kosovel 1977: 102). When Kosovel turned towards “East” for inspiration,

anticipating a “new morning,” this morning, he said, would come “in a red

mantle,” hence its irradiating

core was Russia and not primarily “the Orient” of Tagore (Kosovel 1977: 93).

And yet, of course, the two were closely related. In an important aspect of

Kosovel’s identification with Tagore, therefore, the anti-capitalist and

anti-colonial struggles converged, so the “East” became as much the promise of

a new world order associated with the Bolshevik Revolution as it was evocative

of the old romantic “Orient” that would help heal the deep spiritual “crisis”

of the post-War European generation. At Home in the World I have stressed the links and associations that Kosovel surmised between

himself and Tagore, and which extended his vision beyond the borders of Both artists stressed the role of the individual and

creativity. Kosovel, sharing in the conviction of the post-war generation that

art was as powerful in directing life as politics and economy were, became a

champion of an aesthetic revolution. And “artistic form”, he would insist, “is

but the artist’s personal

relationship with life (my emphasis)”, so that the revolution Kosovel defended

meant above all an on-going revolution of artistic expression in direct

response to life (Kosovel CW III: 657). The

courage to live out life’s contradictions and give it shape in art was for him

a mark of true existence. Kosovel’s raison de etre of human beings was

unambiguous: “I live, therefore I can create”. The model of authenticity was

dropped in favour of a model of creativity. “History does not repeat itself,

but it creates itself,” Kosovel wrote, “so our model should not be in the past,

but in the living present that we feel inside us”. Non-elitist in sensibility,

he explained: “Whatever that life may be, the main thing is that I live it;

that for me is enough”. It is on this affirmative stance towards – and respect

for – lived life that Kosovel took inspiration from Tagore: “Every person’s

life is important, and Tagore is right in saying that human existence is

justified by the mere fact that we live” (Kosovel CW III: 87). Such

affirmative philosophy was the driving force behind Kosovel’s numerous

projects, most of which were cut short by his untimely death. As with Tagore,

there was a strong public side to his personality, and he pursued the needs of

both his private and public self with equal zest and determination. Poetry for

Kosovel was a vital creative force in social transformation; a powerful vehicle

for ideas to be translated into social reality. In this respect too, his

outlook bore close affinities with the Indian poet-educator. Kosovel invested a

lot of energy into setting up an alternative cultural space within We need to raise our

country to the heights of the countries of the world, to the breadth of human

rights, to the depths of ethical problems. That for us is the cultural mission

of Slovenianness (Kosovel CW III: 60). Driven by this mission, Kosovel came to participate

fully in the literary life of the metropolis. A student of Romance and Slavic

languages and literatures at the Tagore’s

vision for India followed a similar trajectory. His whole life was lived under

colonial rule, and yet throughout, he would reiterate with undiminished

conviction that there was one “great fact” about his age, and that was the

meeting of human races. “The human races have been exposed to each other,

physically and intellectually. The shells, which have so long given them full

security within their individual enclosures, have been broken, and by no

artificial process can they be mended again”. This for Tagore was an

irreversible fact of global modernity that required everyone to make a mental

readjustment (Tagore 1996: 71). It meant our countries needed “to harmonize our

growth with world tendencies […] to prove our worth to the whole world not

merely to admiring groups of our own people […] to justify our own existence.”

Problems which had previously been of local make began affecting much larger

areas. Solutions were no longer to be found “in the seclusion of our own

national workshops” but had to be sought in cooperation with different

cultures, through intercultural negotiations (Ibid.: 76). With this aim in view, Tagore set up a world university,

Visva-Bharati, to promote such exchange of knowledge and ideas between

cultures, East and West. What clearly binds these two poets across the vast geographic and

cultural space dividing As Tagore put it in Gitanjali poem

no. 12: The traveller has to knock on every alien door to come

to his own, and one has to wander through all the outer worlds to reach the innermost shrine at the end. (Tagore 2004: 25) And Kosovel in the poem Who Cannot

Speak: You have to wade through a sea of words to come to your self. Then alone, forgetting all speech, go back to the world. (Kosovel 2010: 66) References Bangha, Imre (2008)

Hungry Tiger: Encounters between

Hungarian and Bengali Literary Cultures. Brennan, Timothy

(2002) ‘Postcolonial Studies between the European Wars: An Intellectual

History.’ In: Marxism, Modernity and

Postcolonial Studies. Crystal Bartolovich and Neil Lazarus, eds. Clarke, John, James

(1997) Oriental Enlightenment; The

Encounter Between Asian and Western Thought. Djurić, Dubravka (2003) ‘Radical

Poetic Practices: Concrete and Visual Poetry in the Avant-garde and

Neo-avant-garde’. In Impossible Histories;

Historical Avant-gardes,

Neo-avant-gardes, and Post-avant-gardes in Hogan, Patrick,

Colm (2004) Empire and Poetic Voice:

Cognitive and Cultural Studies of Literary Tradition and Colonialism. Kosovel,

Srečko (1974) Zbrano delo 2

(Collected works 2). Anton Ocvirk, ed. Kosovel,

Srečko (1977) Zbrano delo 3,

prvi Kosovel,

Srečko (2008) The Golden Boat.

Translated and edited by Bert Pribac and David Brooks, assisted by Teja Brooks

Pribac. Kosovel,

Srečko (2010) Look Back Look Ahead.

Translated and edited by Ana Jelnikar and Barbara Siegel Carlson. Lokar, Janko (1914)

‘Lanska tekmeca za Nobelovo književno nagrado.’ (Last Year’s rivals for the

Nobel Prize). Slovan 12 (6): 242–247. Nandy, Ashis (2005)

The Illegitimacy of Nationalism;

Rabindranath Tagore and the Politics of Self. Petrović,

Svetozar (1970) ‘Tagore in Sluga, Glenda

(2001) Difference, Identity, and Sovereignty in Twentieth-Century Europe:

The Problem of Tagore,

Rabindranath (1961) Towards Universal Tagore,

Rabindranath (1996) “Thoughts from Tagore” [1920?], in The English Writings of Rabindranath Tagore:

Volume Three, Miscellany, ed. by

Sisir Kumar Das, Tagore,

Rabindranath (2001) ‘Nationalism [1917].’ In: The English Writings of Rabindranath Tagore: Volume Two, Plays,

Stories, Essays. Sisir Kumar Das, ed. Tagore, Rabindranath

(2010) Rabindranath Tagore; Kratke zgodbe. Selected and introduced by Ana

Jelnikar, translated by Dušanka Zabukovec.

Tagore’s place among artists and intellectuals Kosovel respected –

artists he felt were conscientious in their creative ambitions, striving to

broaden existential and imaginative possibilities of art – is secured not from

some robust act of appropriation, but through a strong sense of shared concerns

grounded in an anti-imperialist, universalist ethos. Tagore was perceived to be

a kindred spirit, not because Kosovel was suffering from some kind of a fantasy

– what after all could a young, still anonymous poet, barely out of his teens,

have in common with a mature, world-renowned figure of Tagore’s stature? – but

because he was able to identify with him and his historical predicament of colonial

subjugation.

Tagore’s place among artists and intellectuals Kosovel respected –

artists he felt were conscientious in their creative ambitions, striving to

broaden existential and imaginative possibilities of art – is secured not from

some robust act of appropriation, but through a strong sense of shared concerns

grounded in an anti-imperialist, universalist ethos. Tagore was perceived to be

a kindred spirit, not because Kosovel was suffering from some kind of a fantasy

– what after all could a young, still anonymous poet, barely out of his teens,

have in common with a mature, world-renowned figure of Tagore’s stature? – but

because he was able to identify with him and his historical predicament of colonial

subjugation.

[1]

From his letters and journals it can be established that he read Sadhana in German, as also Personality (Persönlichkeit, Kosovel 1977: 683). Nationalism was available to him in German or Croatian (tr. Antun

Barac), both published in 1922. Poetry, however, he read in Alojz Gradnik’s

Slovenian translations.

[2] This movement formed around

the review Zenit (Zenith), a leading

journal for the dissemination of new art and culture in the

[3]

Most recent addition to Tagore’s translations into Slovenian is a selection of

Tagore’s short stories, cf.

Tagore 2010.

[4]

For a time Rossegger was closely linked with the nationalist organisation

called Südmark Schulverein, which aided German-language schools in ethnically

Slovenian or mixed territories.

[5]

An article on Gandhi was published in 1922

in the newspaper Slovenec. Kosovel

may also have read Romain Rolland’s book, Mahatma

Gandhi (1924). His notes reveal that he was planning a lecture on “Tagore

and Gandhi: two solutions to the question of nationhood” (Kosovel 1977: 746) as

part of the activities of the Literary

and Dramatic Club Ivan Cankar he co-founded with his colleagues.

[*]

Edinost

(“Unity”): a Slovenian political association, a printing press and the name of

the main Slovene daily newspaper, published in

Published in Parabaas September, 2010.

Ana Jelnikar was born in Slovenia and educated in both Ljubljana and London... (more)

Illustration of Sokovel is taken from Slovenia Cultural Profiles.

©2010 Parabaas